Is MLB's threat to police sticky stuff an effective deterrent for pitchers?

When asked if he'd ever used Spider Tack, which enhances grip and heavy-duty spin, New York Yankees ace Gerrit Cole paused for six full seconds before giving an awkward answer Tuesday.

Last Thursday, Cole made a start a few hours after Major League Baseball announced it would crack down on the usage of sticky stuff by pitchers - ostensibly in an effort to address record-low batting averages and record-high strikeout totals. The announcement came a day after four minor-league pitchers were suspended for foreign substance use. MLB seemed to be firing warning shots in a sport desperate for more balls to be put in play.

In his outing last week, Cole's fastball spin rate dropped by nearly 100 rpm, his lowest mark since July 2018. Cole told reporters he thought it was due to a mechanical issue. It was also below his yearly average in his latest start Wednesday - though still elevated by 300 rpm over his Pittsburgh Pirates tenure - against the Minnesota Twins and Josh Donaldson, who singled out Cole last week for using foreign substances.

Donaldson said someone needed to speak up for hitters and talked again about Cole and sticky stuff Wednesday. Cole struck out nine Twins, including Donaldson twice, in a Yankees victory at Target Field.

"I was not bringing Gerrit Cole's name to the forefront because I'm putting him as the leader in all of this," Donaldson said. "I saw that (drop), and now there's been (other) guys. … (Trevor) Bauer's had to answer questions about it, too. You look at the spin-rate drops with him and other guys, and I think you're going to see what's happened."

Pitchers are in an awkward spot; baseball ignored the issue for years and now any changes will be picked up by MLB's own publicly available Statcast data. A majority of pitchers are thought to be using some form of sticky stuff, and some products are more helpful than others. More spin means more Magnus effect, which means more movement. That leads to more swing-and-miss and more weak contact. Spin and strikeouts are on the rise in the Statcast era.

But has the threat of policing foreign substances produced an immediate deterrent effect? MLB umpires could reportedly begin checking pitchers 8-10 times per game starting as soon as Monday. No one wants to be caught on the mound cheating. Perhaps the threat of being embarrassed or suspended carries a significant incentive to avoid at least the heavy-duty sticky stuff.

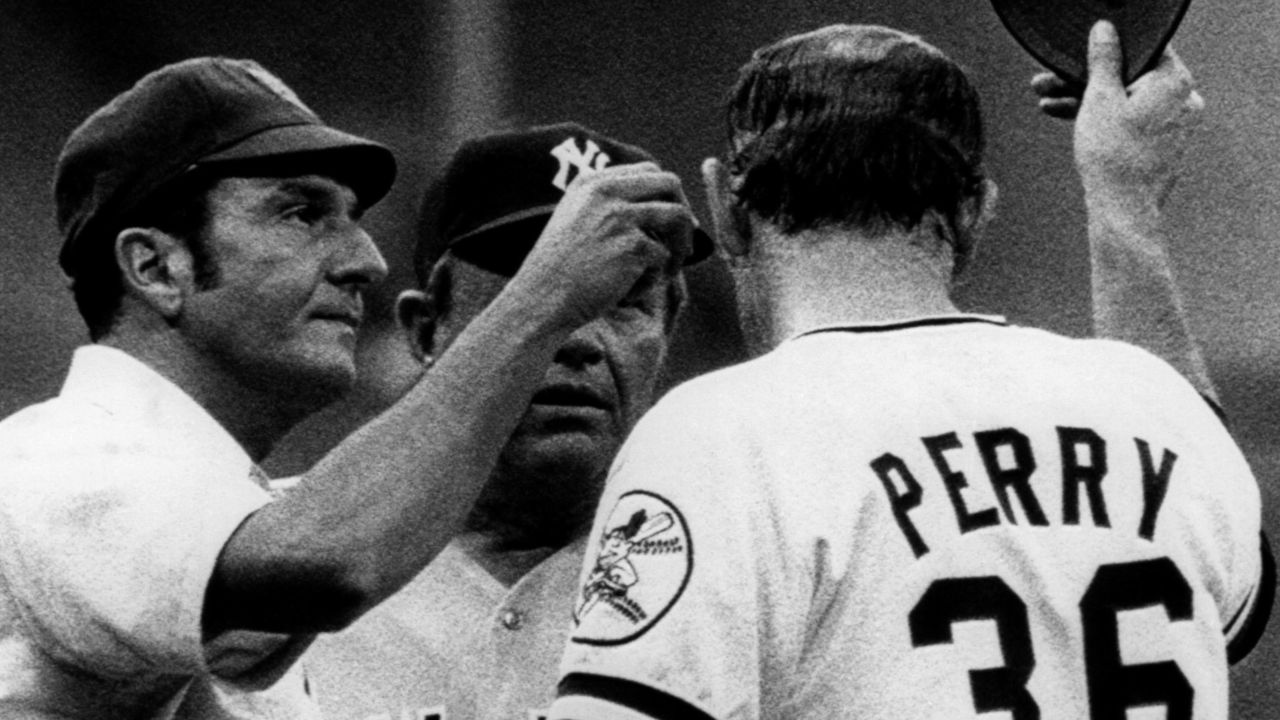

Gaylord Perry, an admitted spitball artist during his long career from 1962-83, said he never wanted to be caught red-handed.

"I'd always have it (foreign substance) in at least two places, in case the umpires would ask me to wipe one off," Perry wrote in his book "Me and the Spitter." "I never wanted to be caught out there with anything though, it wouldn't be professional."

We decided to investigate to see if there's been an immediate drop-off in the use of sticky stuff. It follows our hands-on experiment published last week into the effects of several popular foreign substances on spin rate.

There are only two known ways to increase spin with fastballs: more velocity or sticky stuff. Dr. Alan Nathan, the University of Illinois professor who is a leading authority on baseball physics, told me he doubts there's much a pitcher could do with his grip to increase his fastball spin rate naturally.

Trainers at Driveline Baseball in suburban Seattle found it was nearly impossible to increase rpm/mph ratios for fastballs without more velocity or sticky stuff. They determined pitchers have natural rpm/mph fastball signatures that are constant with velocity change. They dubbed the rpm/mph ratio the "Bauer Unit" because Bauer, their first MLB client, was interested in experimenting with it.

Statcast data shows that 327 pitchers have thrown at least 20 four-seam fastballs since the start of last season and made at least one appearance in which a fastball was thrown since MLB's crackdown announcement last Thursday. Of those pitchers, 207 (63.3%) had a reduction in their rpm/mph ratio; 112 had their rpm/mph ratio drop by half a point, and 45 had at least a drop of one full Bauer Unit.

As we reported last week, Bauer Units have increased in MLB from 24.0 in 2015 to 24.3 in 2018 to 24.8 this season. That shouldn't happen unless players are better at utilizing sticky stuff.

Cole had the hardest-throwing game of his career Wednesday, averaging 98.2 mph with his fastball. Such velocity coupled with Cole's excellent command is tough to hit before considering spin. Although more velocity adds spin on its own, his raw spin measurements and Bauer Units dropped. His rpm/mph averaged 26.1 from the start of 2020 through May and fell to 24.8 and 25.3 in his last two outings.

While pitchers have always looked for an edge, it wasn't until the mid-2010s that spin-tracking tech became widely available for personal use and pitchers understood for the first time the correlation between spin and the effectiveness of their pitches. Those who were curious could investigate how different substances affect spin rates.

Without adjusting for velocity, 185 of 327 pitchers (56.5%) had spin losses over the last week, though some were just a few rpm. But 37 had losses of more than 100 rpm. Those declines raise a red flag. Yes, there can be some variance from pitch to pitch and from start to start, but a 100-rpm change is rare unless it's tied to a velocity drop.

Perhaps this tells us that many pitchers use something, as people like St. Louis Cardinals manager Mike Shildt have said publicly, but not everyone is using Spider Tack.

Overall, from the start of last season through last Wednesday, MLB pitchers averaged 2,312 rpm of spin and 93.5 mph with their four-seam fastballs. That translates to 24.72 Bauer Units.

Since MLB's announcement? The average spin slipped to 2,291 rpm. Fastball velocity is slightly up to 93.8 mph, which equates to 24.42 Bauer Units.

In speaking with some players and coaches in the game and familiar with its practices, there seems to be skepticism that pitchers will immediately stop all use of foreign substances. Instead of using Spider Tack or Firm Grip, they'll likely explore more innocuous sticky substances like bubblegum and hard candy. In our reporting, we found some of those substances to be even more effective, and there are doubts that MLB will be able to police them.

As far as interesting individual cases from the last week, feel free to play along and see if you can guess who fits the following profiles. Hint: They don’t include Cole or Bauer.

OK, pencils down.

Player A is Cleveland reliever James Karinchak, who's posted absurdly good strikeout rates throughout his professional career. Former major-league pitcher Steve Stone, the color commentator on White Sox telecasts, commented recently about Karinchak possibly using sticky substances.

White Sox broadcast going right at Indians pitcher James Karinchak for allegedly using sticky stuff

— Jomboy Media (@JomboyMedia) June 2, 2021

(h/t @bbletter) pic.twitter.com/Nb0j9LU1LP

He's thrown just a few fastballs since MLB's announcement, but it can take just one throw to see the benefits of sticky stuff, as I learned first-hand. Karinchak had the fourth-greatest drop among players we studied.

Player B is Milwaukee Brewers relief ace Josh Hader, who owns the 12th-greatest drop since last week. Hader has never been a high-spin pitcher - his fastball dominance is due to his unusual arm angle and unusual spin efficiency from that arm angle. But he has had one of the greatest rpm drops of the last week. Hader's last 22 fastballs since Thursday have averaged 1,886 rpm despite being thrown at 95.9 mph. It's an outlier reading for low spin.

In our own hands-on experiment, my 59.1-mph fastball had 1,810 rpm when adding Spider Tack.

Player C is the best pitcher in baseball, Jacob deGrom, whose rpm/mph hasn't changed much since MLB's announcement. While his spin is slightly up, so is his velocity. It's tough to hit 100 mph, and deGrom's spin gains may be explained by his velocity gains.

The point is that many people will be analyzing spin data going forward: It's public data, and spin is a big factor in pitcher performance.

As we noted in our "Take This In" video series, MLB batters are hitting .260 against fastballs with 2,250-2,350 rpm of spin this year, a league-average range.

Against fastballs with 2,600 rpm or greater? Batters are hitting .209.

MLB can rightfully be criticized for ignoring sticky-substance issues for years. Bauer blew the whistle in 2018, saying he believed it was a performance edge greater than steroids. After baseball did nothing, Bauer increased his own spin rate at the start of 2020 (it declined in his last start).

But MLB also knows there is a problem with strikeouts and dwindling balls in play, and it's probably most strongly tied to the quality of stuff from the mound. Before trying something radical like moving the mound back, it makes sense to target lower-hanging fruit. And so far, it seems the threat of enforcement alone will compel change.

Travis Sawchik is theScore's senior baseball writer.

HEADLINES

- Chisholm tweets soon after ejection: Pitch wasn't 'even f-----g close'

- Roberts: Ohtani's return to pitching still 'a couple months away'

- Rangers' Corbin beat Angels after being bitten by venomous critter

- Pirates baseball: Three rivers of fan angst and animosity

- Rocker earns 1st MLB win, Bochy ties Baker as Rangers sweep Angels