For seven weeks, Buffalo took its bows on baseball's big stage

BUFFALO - Painted across the concrete roofs of both dugouts at Sahlen Field this week, placement unavoidable to anyone in the facility, was a simple message: "Thank you, Buffalo."

The city name, "Buffalo," was painted in the Blue Jays' split-letter font.

As Toronto took batting practice Tuesday, a 10-year-old fan from Rochester, New York, stood near the home dugout holding a poster that contained a handwritten message and photographs from his family's experiences here. The message: "Thank you, Blue Jays."

The Blue Jays and Buffalo have had something of a symbiotic relationship since 2013, when Toronto moved its Triple-A affiliate there. It grew closer in 2020 when the displaced Blue Jays renovated Sahlen Field and played 26 fanless home games there. It deepened even more over the last seven weeks, with fans able to attend the first major-league baseball games in the city in decades.

Buffalo offered a more friendly home environment than in Dunedin, Florida, and home-field advantage matters, perhaps a great deal, in what figures to be a close chase for a playoff berth. Buffalo was also close enough to allow front-office members and other team officials to commute back and forth from Toronto. This was the best baseball Airbnb spot the club could hope for.

Buffalo fans got their moment with major-league baseball, which so many have wanted for so long. It provided a civic boost and placed a spotlight upon a Rust Belt city reinventing itself after decades of decline. The Lake Erie port was a forgotten baseball outpost, yet one whose influence is felt in most major-league cities and their ballparks.

What follows is a snapshot in time about a minor-league town that briefly became a major-league city. It's about where the games were played, what it was like to play in Buffalo, and what it meant to watch.

When I arrived at Sahlen Field at 3 p.m. Monday - a gorgeous, low-humidity, sun-soaked afternoon - I was told I had to speak with Doug Frank. He's Buffalo's baseball encyclopedia.

When the Buffalo Bisons were reconstituted as a Double-A franchise in 1979 after nearly a decade without baseball, Frank, 70, a Buffalo lifer, was one of the first people hired by the club. He worked part time in the ticket office and full time for patient accounts at a Buffalo hospital.

I found Frank on Monday afternoon with a digital ticket scanner in hand outside the third-base gate. A few fans in Boston Red Sox gear were waiting for the gates to open. Until this year, Frank had never witnessed a regular-season major-league game in Buffalo. No one had one since the barnstorming Negro League teams stopped to play here. It's inconceivable that anyone alive today saw Buffalo's Federal League team, the Blues, play in the city in 1914 and 1915. Buffalo also had a National League team in the 19th century.

Frank recalled thinking the idea of MLB expansion in Buffalo in the early 1990s was a pipe dream, even when the Bisons drew 1.24 million fans in 1991 and were considered for MLB's 1993 expansion. He never thought he would see an official major-league game here.

He said he hasn't felt energy like this in the city on a summer night in years, if ever. What if Buffalo could get another 15,000 people to live and work downtown again?

Sure, they had big crowds for "Star Wars" night in recent years and various other "superhero nights," he said, but those crowds weren't truly there for the game. The noise was different in the major-league games. So were the ticket prices, ranging between $70 and $137 for Tuesday's night game.

"Crowd noise is the best I've heard in years," Frank says. "The Vlad home runs …"

He trails off, but doesn't have to explain. Vladimir Guerrero Jr.'s home runs are very cool - they inspire a different reaction. Guerrero hit 15 home runs as a major leaguer in Buffalo, including another in the final game here Wednesday.

Vladdy makes US wanna shout 💥 #PLAKATA pic.twitter.com/dPZjwEsqzl

— Toronto Blue Jays (@BlueJays) July 22, 2021

The roar of the crowds here also struck Blue Jays president Mark Shapiro.

When Blue Jays pitcher Robbie Ray struck out the side against the Miami Marlins on June 1 in the team’s first game in Buffalo this year, the crowd erupted, and Shapiro remembers that sound. It was the first time in 611 days, since Sept. 29, 2019, that the Blue Jays heard a crowd roar in their favor.

When playing regular-season games in Dunedin this spring, capacity was limited to 1,000 and those in attendance were often rooting for Toronto's opponent. Canadian snowbirds had long since been summoned home by the government, and many Gulf Coast Floridians are transplants from the northeastern United States.

"We were the visiting team every game. Every game," Shapiro said. "We had no fan base there. The other teams we played did. The Phillies, Braves, Red Sox all had strong fan bases so we were the visiting team every night."

As the authors of the book "Scorecasting" argue, the crowd is the largest factor in home-field advantage because of its influence on officials and umpires. Most notably in baseball, it shows up with the home team more often getting favorable calls on borderline pitches.

While it's a small sample, the Blue Jays were 10-11 in Dunedin this year and 12-11 in Buffalo. Perhaps playing in Buffalo versus Dunedin swung a game or two in their favor. But the Blue Jays have a better record on the road (26-22) than at home, which is unusual for any team. The Blue Jays have also underperformed their expected win-loss record; based on their run differential, they should be closer to 55-37 (they're 48-44 going into Friday).

Where would the Jays be had they been able to play in Toronto? But where would they be if they had to play all their games in Dunedin? Perhaps even further behind the Red Sox.

"Dunedin was kinda tough because I felt like we never had fans of our own," third baseman Cavan Biggio said. "Even if we were playing the Braves and Angels, there always seems to be more opposing fans than us. Buffalo has been better."

The Blue Jays averaged 7,733 fans per game in Buffalo, more than three major-league teams this season: Tampa Bay, Oakland, and Miami. They'll play in front of a capped limit of 15,000 at the Rogers Centre when they return home from their current road trip to New York and Boston.

As Monday afternoon turned into Monday evening, the crowd grew outside the three gates. Staff made their final preparations in the concourse. Beer kegs were shuttled around. The team store prepared for customers.

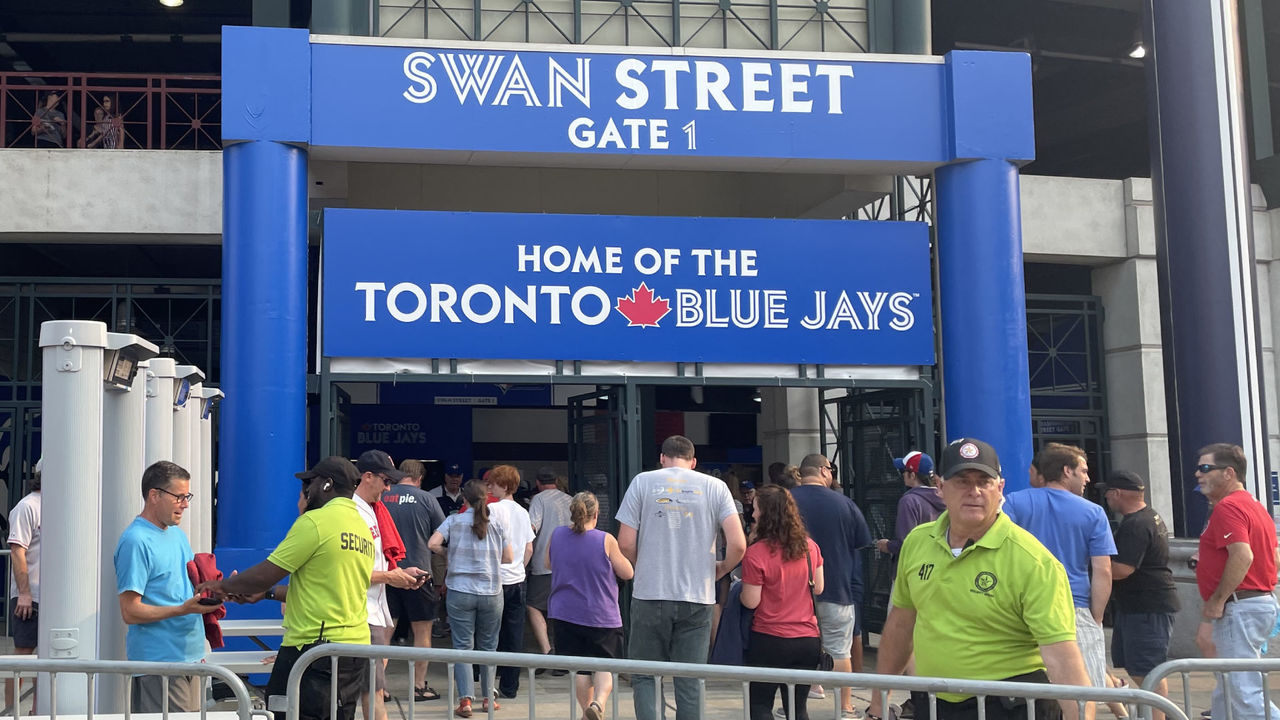

Across Swan Street, fans spilled out onto Union Pub's patio. Before games, it regularly reached capacity. The patrons - mostly millennials - wore Bichette and Guerrero jerseys, and Red Sox supporters were represented, too. Boston fans travel well. Biggio said he's seen 20-somethings like him on the streets sporting "Buffalo Blue Jays" T-shirts. This was a different energy than a Bisons game.

Over the years, Frank's watched so many people leave the city. Buffalo was once an important stop on the Great Lakes. It was the world's largest grain port, he notes. For some time, geography was part of its advantage: the city rests where the Erie Canal, Lake Erie, and rail lines converge. At one point, it was the 13th largest city in the United States. But when the St. Lawrence Seaway opened in 1959, Buffalo was bypassed as a port destination. Industries were lost that will never return. The city's population is half what it was at its 1950 peak.

When arriving from south of the city, the highway is lined by abandoned steel mills, warehouses, and grain elevators, one of which features its silos painted to appear like a six-pack of Labatt Blue.

"We lost a generation," Frank said. He corrects himself: two generations.

The baby boomers and their kids mostly left, he says, especially those who went off to college. Buffalo is the smallest city in North America to host two major pro sports teams: the NFL's Bills and NHL's Sabres. Frank isn't concerned about one of those franchises moving away, but some of his friends are worried about the Sabres' future.

He's encouraged that millennials seem to be staying in greater numbers, moving into loft apartments downtown and refurbished Victorian homes in the Allentown neighborhood. In fact, Buffalo's millennial population grew by 10% since 2006, while its overall population declined by 1%. And those young people piled into downtown for baseball over the last seven weeks.

"Now we got a chance to come back," Frank said.

As if to underscore his point, Frank is working near a young security guard, Peter Tripi, 21. He wore the fluorescent yellow polo shirt worn by all the security guards and a Blue Jays ball cap.

"I try to work as many games as possible because it is crazy," Tripi says. "It will never happen again."

I asked Tripi if he interacted with any of the major leaguers. He said he was working in the dining hall one night when he overheard Blue Jays catcher Reese McGuire debating a teammate about where he should get wings.

"'We should go to the Anchor Bar, that's where the Buffalo wing came from,'" Tripi recalled overhearing. He couldn't help but interject.

"'Oh, no,'" Tripi recalled. "'You don’t want to go there. Go to Duff’s or Elmos.'"

A colleague of his, Randall Ammerman, a gray-stubbled retired police officer, suggests it's somewhat fitting Buffalo was the caretaker of the Blue Jays because of the broader relationship between the cities - Toronto being the "big brother," he said.

They have a lot in common, too, he notes. "We hate Boston as a city," he said with a grin. "What the Bruins have done to the Sabres for 40 years, and what New England has done to the Bills forever …"

The Blue Jays said Buffalonians were great hosts. And Sahlen Field got to show off in the major leagues after quietly influencing other MLB teams for more than three decades.

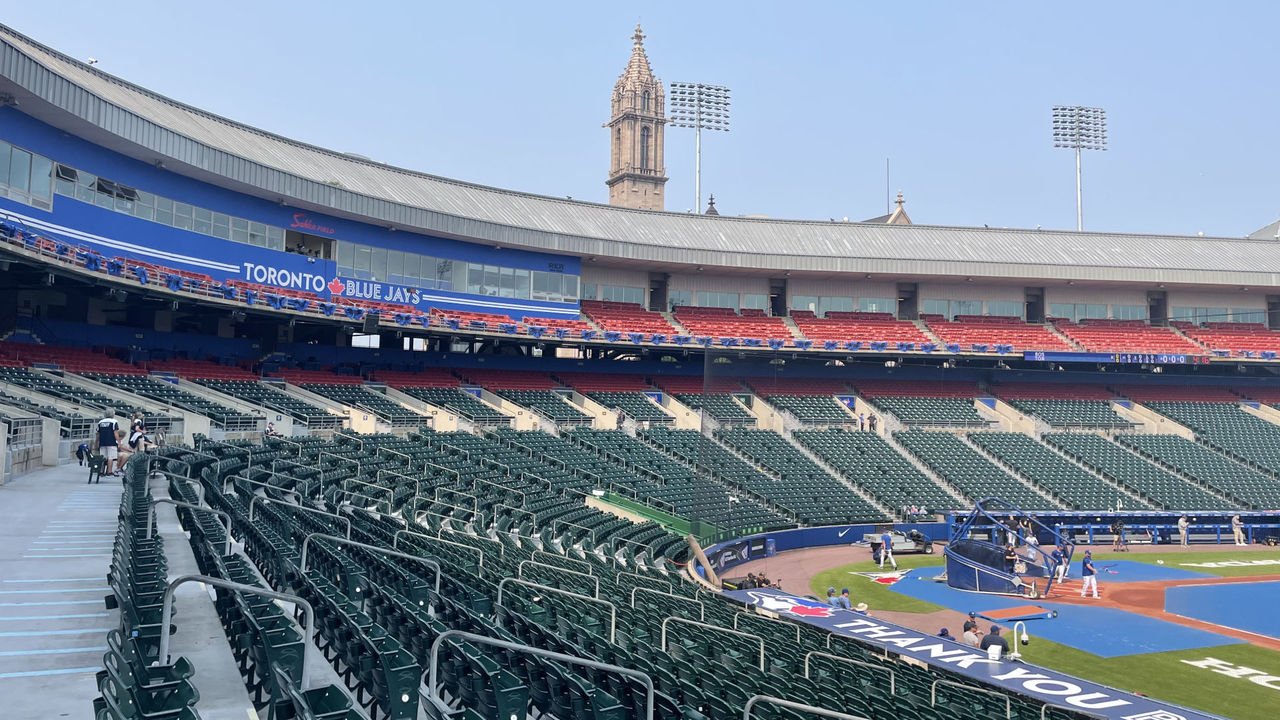

Frank remembers walking into the new stadium for the first time in 1988 and thinking it was beautiful, something "very different" than the old multi-purpose War Memorial Stadium. It was different than anything in baseball, period.

Sahlen Field isn't a large place. It features one deck and a mezzanine level. It’s not particularly impressive or imposing as a standalone structure. One reason Blue Jays second baseman Marcus Semien can't want to be back in the Rogers Centre and other large ballparks is to have the third, fourth, and sometimes fifth decks help cut down the wind.

Named Pilot Field to start, the ballpark was supposedly designed to be able to be easily expanded if an MLB club ever decided to call Buffalo home. It was a paradigm shifter because it was not surrounded by a sea of parking lots. Rather, it fits within the existing city at the corner of Washington and Swan Streets. It's not suburban. It doesn't feel grand like a stadium. It's a ballpark inside a city. It's charming. It features arches and exposed ironwork on its exterior facade. It was the kind of place that hadn't been built to host baseball since the jewel-box parks of the 1910s.

Initially, in the mid-1980s, Buffalo officials wanted to build a 40,000-seat, multi-purpose facility on the same parcel of land. But when the state cut back on funding, the architectural firm HOK (now called Populous), proposed a different vision: an open-air, retro ballpark. What rose across from the 10-story, granite-block, Italian Renaissance-style Ellicott Square Building was a structure "widely respected as the first postwar example of a baseball park successfully integrated into the urban fabric of an older city," architectural critic Paul Goldberger wrote in his book, "Ballpark: Baseball in the American City."

"[It] sat comfortably within the downtown grid of streets like the ballparks of an earlier era," he wrote.

Like Fenway and Wrigley before it, its asymmetric design was due to the constraints of building within a tight urban space - not an inorganic architectural flourish.

The on-ramps to I-190 and the Peace Bridge run behind the left-field wall. Guerrero Jr. cleared the protective netting in at least one game, and routinely did so in batting practice, once smashing the passenger window of a vehicle of a woman trying to enter the highway.

Here’s the evidence 👀 #PLAKATA https://t.co/wo9h3ie38a pic.twitter.com/HtbHKPhNDe

— Ty B (@tyBuffalo) June 16, 2021

The Orioles were paying attention when the park opened. Larry Lucchino, then an executive with the Orioles, pushed for what became known as the retro or neoclassical model for Camden Yards in Baltimore. It stands in contrast to what the Chicago White Sox did with what is now known as Guaranteed Rate Field, widely viewed as a design failure.

Lucchino grew up in Pittsburgh. He went to games at Forbes Field, which was built at the time of Wrigley and Fenway. It was a neighborhood ballpark. Lucchino saw it replaced by a multi-purpose facility, Three Rivers Stadium, which forever shaped his view of what an MLB facility ought to be.

Including Camden Yards, 23 ballparks have opened since 1992 in the majors. If you toss out the two suburban ballparks in Texas and Atlanta, they average 0.6 miles from their city centers, according to the Clem’s Baseball stadium database.

Then Buffalo mayor James Griffin - famous for telling Buffalonians to "Stay inside. Grab a six pack," during a mid-1980s lake-effect blizzard - helped bring the Bisons back and hoped to lure an MLB team. He at least hoped the stadium would be a reason for Buffalonians, who fled to the suburbs, to come back - at least for an evening or two.

While change didn't occur overnight, the harborfront here is transformed. There are new hotels, new restaurants, and new apartments downtown. The ballpark spurred some of this. It's what all the cities and states that poured public tax into a stadium hoped would happen to their urban core.

Tripi estimated that 70% of the 170,130 fans to pass through the gates since June 1 have been western New Yorkers. Frank agreed, give or take. Large northeast fan bases - primarily Red Sox and Yankees supporters - showed up too.

Frank was surprised by how many Orioles fans arrived, though many of those families paired the trip with a visit to nearby Niagara Falls. Mostly, though, it was locals. They adopted the Blue Jays.

Shawn Scotney is from Rochester, about 75 miles to the east. During Tuesday's early rain delay, I met Scotney in the loud and crowded lower concourse. He told me to look for the tall guy in the Guerrero All-Star Game jersey - it was tough to miss him.

Scotney's parents were Blue Jays fans, so he was born into it in a region where MLB allegiances vary. His son, Jack, was the 10-year-old with the large homemade thank you card. Father and son attended eight of the 23 games played here.

They arrived for each game when the gates opened and would get right up to the first row behind the field. It felt like a spring training back-field environment. Only this was the regular season. Scotney had to remind himself this was real. He knew they'd never have an MLB experience like this one again.

"It's the best summer ever," Scotney said.

They went often enough that Blue Jays rookie pitcher Alek Manoah knows his son by name.

"That was the coolest thing," he said.

What an incredible ride it’s been. Thank you, @BlueJays for making this boy’s summer.

— Shawn (@shawnsJays) July 22, 2021

A 10 year old doesn’t see OPS, blown saves, and quirky bullpen moves, he sees his favorite players up close and personal in a way he’ll never forget. And the joy I saw in him, I won’t forget. pic.twitter.com/N787NHApG4

There are few modern precedents for what the Blue Jays have experienced over the past two years.

The 2003 Montreal Expos played 22 games in San Juan, Puerto Rico, but that was planned well in advance for a team on its way out of Quebec.

On July 19, 1994, four ceiling tiles in Seattle's Kingdome fell to the field and the facility was closed. The Mariners played the rest of the strike-shortened season on the road.

Teams in New York City have shared stadiums, often due to new stadium construction, but the Blue Jays' traveling roadshow is unmatched. Their last 70 "home" games covering 22 months were played out of their country.

Semien knew it could be a chaotic year when he signed with the Blue Jays. He and his wife have three young children, ages 5 to six months. They decided to take on a long-term lease in the Tampa area for spring training and the early season. But when it came to Buffalo, it was difficult to find a place.

"We had a little less than a month to figure it out," Semien said. "Not ideal with three little kids."

They stayed in a hotel during Toronto's first homestand in Buffalo. Then they found an apartment, but needed to furnish it.

"The tough part here was finding furniture to rent," he said. "I'm sure they were swamped when we came at the same time."

He's now looking for a place in Toronto. In August, his family leaves for California, their offseason home, and where his oldest son will begin school.

"That will be tough. A lot of families go through that," Semien said. "The good thing is they were able to be with me."

What made it a little easier: Semien's oldest loves baseball. Before afternoon games, he and his son hit in the new indoor batting cages the Blue Jays built at the park this season. The Blue Jays also expanded the visiting club facilities, which reside in a giant tent beyond the right-center field wall. The Triple-A Bisons will inherit it all.

For some, it'll get harder with the move from Buffalo - Blue Jays pitcher Ross Stripling will not have his wife and 5-year-old son travel to Canada.

I asked Toronto manager Charlie Montoyo where he was staying. He pointed toward a hotel high-rise visible beyond the first-base grandstand.

He believes the Jays haven't been credited with how well they've dealt with this turbulent season.

"You're talking about moving families," Montoyo said. "You're talking about leases, the clubhouse guys moving four times. It's a lot of moving parts. These guys haven't complained the whole time."

Single, without children, it was easier for Biggio. He stayed in hotels in Buffalo. He knows the city well from playing here in 2019 on his way to the big leagues. His routine included walking to Starbucks each morning. He usually went unnoticed.

"I always use a different name," Biggio said of his coffee orders. "Ever since I was in high school, I'd say, 'Cav,' and they'd be like 'What?' I’d have to repeat myself a few times. I just say Kevin or Kyle. I respond to both of them."

Biggio said he felt a "warm" reception from fans in the ballpark, but he's ready to be back in Toronto.

"Buffalo has been really good to us, but I definitely miss the fans in Toronto, the energy we had in 2019," he said, "and what I saw in the '15 and '16 playoff teams."

Millions have watched another Buffalo-based baseball campaign that included a freakish talent - albeit a fictional account. "The Natural" ranks as the No. 7 baseball movie of all time by MLB.com. It was filmed primarily in Buffalo and other nearby locations. Frank can surely point out all the sites.

In the 1984 film, War Memorial Stadium was cast as the New York Knights' home. Director Barry Levinson scoured the United States looking for a minor-league stadium that could look like a Depression-era ballpark. War Memorial, a WPA project built in 1937, had hardly changed since its opening.

The stadium was perfect and so were other locations like the Buffalo Central Terminal, where rail traffic ended in 1979, and the Armory, where set designers built the Knights' clubhouse, the owner's office, and Max Mercy's press box.

The Armory is where Wilford Brimley playing the role of Knights manager Pop Fisher told Robert Redford playing Roy Hobbs that he was "the best goddamn hitter he ever saw."

Fisher never saw Guerrero Jr.

Hobbs was the fictional natural. Guerrero Jr. showed Buffalonians he is of the real-life variety.

Vladdy’s 2nd HR of the night is his 30th of the season, and it got LAUNCHED. 😮💥

— theScore (@theScore) July 17, 2021

(🎥: @MLB)pic.twitter.com/7H3mmrkAlR

Ask Tripi, Frank, and the Scotneys about what they'll remember about this time and Guerrero's name comes up quickly.

Tripi recalled a game against the Orioles when Guerrero saw two pitches in his first two at-bats, and took two swings, smashing a double and a home run.

"From the games I've gone to, Vlad has been the coolest thing," Tripi said. "He’s a freak. I've never seen anything like it."

The show ended Wednesday with a 7-4 loss to the Red Sox.

Lourdes Gurriel Jr. was the final batter, grounding a ball to Rafael Devers, who threw across the field for the last out. On the center-field video board, a "Thank you, Buffalo" message appeared as the fans filtered out. The Red Sox shook hands on the field. Guerrero gave a pair of his batting gloves to a young fan and disappeared into the dugout tunnel. Major League Baseball left seven weeks of memories. Just like that, it was gone.

Travis Sawchik is theScore's senior baseball writer.

HEADLINES

- Ohtani is back in Miami, where he's had some magical moments

- DeRosa 'was well aware' losing to Italy could eliminate U.S.

- WBC odds: Dominican Republic closes in on favorite U.S. ahead of quarterfinals

- Aaron Judge card sets modern-era record with $5.2M sale

- Dominican powers past Venezuela to finalize WBC quarterfinals