An MLB lockout brings immediate uncertainty and maybe future chaos

The past few days brought a rare frenzy of early offseason free-agent deals as teams try to lock in cost and roster certainty ahead of a potential lockout that's expected to arrive just before midnight Wednesday.

Still, that flurry of activity could be dwarfed by what happens on the other side of this labor fight. If it's a long lockout, as many in the industry fear, chaos could ensue as everyone rushes to start the season.

The most bitter labor dispute in baseball's labor history began Aug. 12, 1994, and wiped out the World Series that fall. But there's less recollection of what happened in spring 1995 after U.S. District Judge Sonia Sotomayor (who joined the U.S. Supreme Court in 2009) issued an injunction against the owners, and players returned to work.

There was a lot to get done. Many players were still unsigned free agents on April 2, 1995, when the strike ended. Arbitration cases hadn't been decided, and abbreviated spring training camps were to set to begin April 7. Opening Day for most teams was scheduled for April 26.

If this lockout is as contentious as many expect, with the two sides reportedly far apart as they meet in Texas this week, what happens afterward could play out similarly to 1995. And there was a lot of activity that spring.

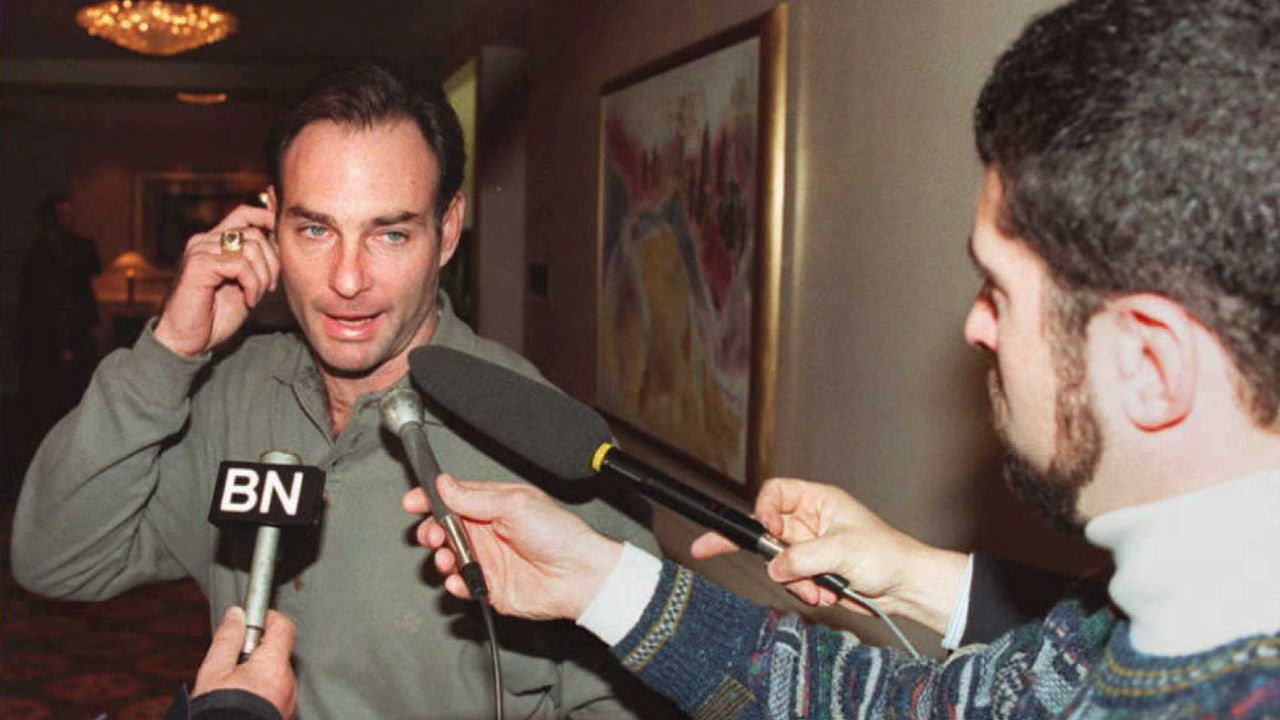

On April 3, 1995, Dennis Eckersley became the first free agent to sign a major-league deal after the strike ended - and the first since Dec. 23, when the owners tried to force a salary-cap system and players stopped signing deals. But a lockout, unlike a strike, will freeze all major-league business.

From April 3-26, 1995, 140 free agents with major-league experience signed contracts. That's six contracts per day, and there were two fewer MLB franchises then.

During the first 100 days of normal offseasons from 2013-14 to 2018-19, major-league free agents signed at a rate of 0.73 contracts per day.

Two days after Eckersley signed in '95, John Franco, Dave Winfield, and Fernando Valenzuela agreed to deals. On April 7, Mark Grace and Kirk Gibson signed. A day later, as players began to report to camp, Orel Hershiser and Larry Walker were among the players to sign contracts.

Over the eight-day period from April 5-12, 95 major-league free agents signed, which the Los Angeles Times described as a "dizzying pace." It had the feeling of the NBA's or NFL's free-agent signing periods. Later that month, well-known players such as Andy Van Slyke (April 21), Frank Viola (April 24), and Bud Black (April 25) were still agreeing to deals.

"There will be a frenzy when the lockout ends," one agent told theScore.

And it could be favorable for teams, which have found better deals in recent springs by waiting longer and longer.

This November, MLB players have already exceeded $1 billion in contracts, blowing away the total dollar amounts of recent Novembers. Those deals have mostly gone to a select group of star-level players, though. Agent Scott Boras seemed intent on ensuring the biggest names on his client list - Marcus Semien, Corey Seager, and Max Scherzer - signed before the lockout. Semien and Scherzer are also two of eight members of the MLBPA's executive player committee.

While the total number of players signed is within the range of recent November periods, teams usually haven't given out big contracts this early in the offseason.

This November's megadeals may signal that MLB owners aren't all that concerned the terms of the new collective bargaining agreement will change dramatically. One MLB executive told theScore that some of the recent deals are player-friendly, an indicator that "things may not be so bad" between the two camps.

The one-percenters generally always do well in free agency, and they are certainly getting paid this month. But one agent who spoke to theScore is concerned about what a long lockout could mean for the majority of remaining free agents. There could be a huge supply of unsigned players when a lockout ends, and the clock will be ticking.

"The big-money guys will get their deals," the agent said. "A salary floor would be the only thing that could help the lower- and middle-class guys."

A salary floor, proposed by MLB last summer, doesn't seem to be of interest to the players' union if it's attached to a lower luxury-tax level, which the owners would likely demand.

Then there's the matter of arbitration-eligible players.

Post-strike in 1995, players could file for arbitration by April 14, and the teams and the players exchanged salary numbers by April 28. Players started the season being paid at the level of the club's offer until their cases were heard. Players who won were awarded back pay with interest.

It may require a similar setup to get through arbitration quickly after a potential lockout, as the process can take several weeks during a normal offseason. Teams and players usually exchange salary demands in January and any necessary hearings are held before spring training.

A condensed offseason could be good news for fans who get to experience an exciting, transaction-filled period that's closer to the free-agency windows in the other three major pro sports. But it might not be great for the free agents still available after a lockout, or for the teams that didn't complete their major shopping before the CBA expired.

Much uncertainty is on the horizon if the owners declare a lockout. And no one knows for sure what awaits on the other side.

Travis Sawchik is theScore's senior baseball writer.