The future of TV sports, Part 1: How we got here

Sports television will not be immune to the digital forces that have rocked the rest of the media and entertainment worlds. Cord-cutting and improved streaming options are already having an impact on regular TV. Live sports may be the last anchor keeping households tied to cable and satellite plans, but that ground is shifting quickly. In this three-part series, theScore's Travis Sawchik explores where sports television content might be found in five years. In Part 1, he looks at how we got here. All three parts are available to read now and will be highlighted in the app throughout the rest of the week.

- Part 2: Where we're going

- Part 3: How it looks in Canada

Nick Alexander cut the cord with cable television a few years back. The suburban Cleveland resident and avid fan of the local pro sports teams no longer wanted a bulky cable box or the rental and DVR fees associated with them. There were dozens of channels he never even watched. Why was he subsidizing them? He wanted to save some money, sure, but like many millennials, he also liked the convenience and choice offered by a la carte streaming.

Early in his post-cable existence, in 2019 and for most of 2020, Alexander was able to keep watching what he loved most: broadcasts of Cleveland's NBA and MLB teams. He'd watched them on cable since he was a kid.

But beginning in late 2019, he noticed his streaming bill kept getting bigger. He initially subscribed to Hulu Live TV for $45 a month, which carried Bally Sports Ohio, the regional sports network that holds the rights to Cavaliers and Guardians games. Hulu increased its monthly charge to $55 in November 2019, and then to $65 in November 2020. A big reason for the increase, he knew, was regional sports networks (RSNs) and ESPN kept increasing their fees to offset the cord-cutting they were enduring.

Live sports channels are the most expensive part of a cable bundle. For instance, Bally Sports Ohio, one of 19 Bally-branded channels owned and operated in a joint venture between Sinclair Broadcast Group and Entertainment Studios, took in an estimated $7.42 per month per subscriber, the second biggest fee in the U.S., according to Kagan Research.

As sports channel fees increased and as millions of customers continued to cut cords, more and more RSNs were dropped by traditional cable providers and live-TV streaming alternatives. In 2019, Sling TV and Dish Network couldn't reach a deal with Sinclair to carry all 21 RSNs it co-owns. In September 2020, YouTube Live failed to reach an agreement with Sinclair. And a month later, Hulu Live also dropped the Sinclair RSNs.

Alexander was left in the dark.

"I was just blown away that I couldn't watch the Indians and Cavs, and I know I'm not alone," Alexander told theScore. "It blew my mind that it wasn't an option as a local fan."

He didn't want to go back to cable. He hoped Hulu or YouTube and Sinclair would work out an agreement. They have not. So in 2021, for the first time in his existence as a sports fan, he didn't have access to Cleveland baseball games.

"I don't know how you keep a fan base, locally," he said. "How do you keep local fans if they can't watch the teams? As a kid, I watched the Indians and Cavs all the time. It was available to me."

For nearly a year, Alexander didn't have access to those local MLB and NBA games. But as the Cavaliers became one of the surprise success stories early in this current NBA season with young players like Darius Garland and Evan Mobley excelling, he felt compelled to watch. He scoured his options and found there was one way to watch the telecasts without a cable or satellite TV package: through AT&T TV, a streaming service now branded DirecTV Stream. But it was a pricey $86.40 per month, which jumped to $97.20 per month in May - Alexander signed up that fall - and increased again to $100 in January.

"I'm subscribing to DirecTV (Stream) at this point just to watch Bally Sports," he said. "Besides getting the news, which I could get elsewhere, I'm paying $100 a month to watch the Cavs.

"If the future is direct-to-consumer, sign me up."

Right now, sports TV is in the middle of a turning point. Alexander's experience illustrates the turmoil in the marketplace. There hasn't been a smooth transition to what's next as consumers part with their ties to broadcast and networks, and to the cable and satellite tethers that fed them what they desired. So what might the future of how we consume live sports look like?

The old models face existential threats from changes to consumer habits and new technology. How we watch live sports could change dramatically in the coming years and have wide-ranging effects, maybe even including diminishing league revenues and player salaries. The future could be more consumer-friendly, with more competition among leagues and streaming providers for viewers.

The trends are already taking shape: Young people are already watching less live sports than previous generations. But there's also the threat of live sports being less accessible if they are detached from a cable or streaming bundle. The future is likely going to look much different, and we're interested in gaming out what it might look like in five years.

A brief history of cable

First, we need to understand how we got here, why change is coming, and how quickly it might arrive.

Televising the vast majority of professional sports teams' games wasn't always obvious.

Owners of sports franchises have always feared new technology.

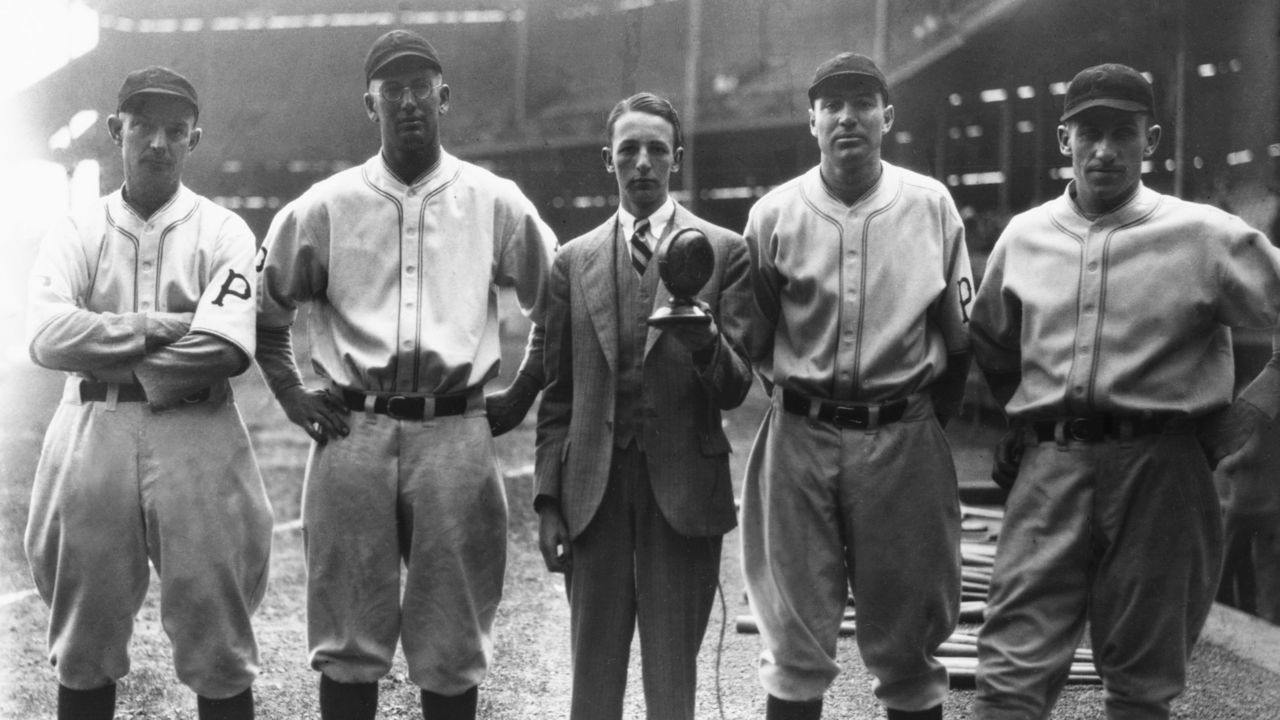

After the Pittsburgh radio station KDKA first broadcast a live, team sporting event - a Pirates-Phillies game in 1921 - owners were reluctant to embrace radio, fearful of what it might mean for their gate receipts. It wasn't until 1939 that all MLB teams had local radio broadcasts of their games.

Having fans be able to see games via television, not just hear them via radio, was an even more terrifying prospect.

While only 9% of American households owned a television in 1950, 86% did by 1959. But regularly televising local sporting events wasn't something that happened often until the 1980s.

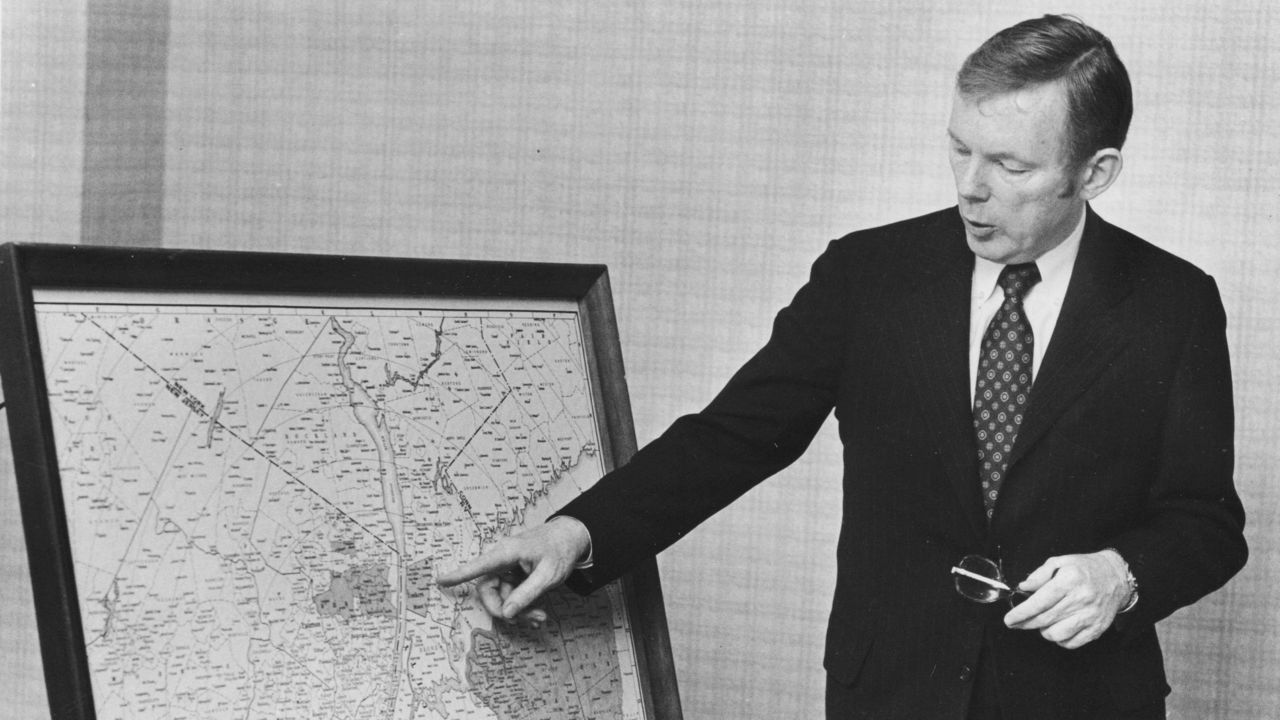

Greg Bouris worked for a RSN, the SportsChannel, as well as for pro teams, and for the Major League Baseball Players Association in a long career as a sports industry executive. He's something of a historian of sports media and is now a professor at Adelphi University, where he's director of the undergraduate sports management program.

"For the longest time in sports, you didn't get a lot of your games on TV," Bouris said. "(In the 1950s) people weren't going to give up 'The Honeymooners' to watch games (on prime-time network TV), so you got Fridays and Saturdays. Teams didn’t want to put home games on TV. Income was generated from the gate. Fast forward to the late 1970s, and Charles Dolan is trying to sell Cablevision. The (New York) Islanders are winning. 'Hmmmm,' he thinks, 'Let me try to get rights to a very popular hockey team.'"

In the mid-1960s, the Dolan patriarch was wiring lower Manhattan apartments so subscribers to his nascent service, HBO, could watch movies in the comfort of their living rooms. He would then sell HBO to begin something more ambitious: an early cable network, founding Cablevision in 1973. Dolan wanted to wean viewers from network TV, what he referred to as a "wasteland," and offer not just a commercial-free movie channel, but a business channel, weather, 24-hour news, and sports. He wanted to give the consumer more choice.

SportsChannel launched on Cablevision on March 1, 1979 as one of the first regional sports networks. The Islanders were the first team Dolan signed up. The Islanders were at the start of their heyday, winning four straight Stanley Cups from 1980-83.

"The contract was contrary to all sports franchise wisdom," The New York Times wrote of the rights deal in 1982. "The Islanders have effectively expanded their audience beyond the 15,230-seat capacity of the Nassau Coliseum to include the 230,000 subscribers to SportsChannel."

After their initial deal in 1979, Islanders owner John Pickett signed a 30-year deal with Cablevision in 1982, which did not pay a flat fee, but instead took an 18.5% cut of all SportChannel revenues. It was a groundbreaking deal in terms of its length, value, and that the club tied all of its television rights to cable. By the mid-1980s, nearly all the club's games were televised on SportsChannel. They were trailblazers.

It was a smashing success for the club, which by the mid-1990s was receiving from the deal almost as much as the NHL received for its national rights package from ESPN. In pro sports, the cable deal's revenue for the team was topped only by the New York Yankees. (Eventually, the Islanders and SportsChannel renegotiated a flat fee.)

The Islanders began the RSN boom.

"Others took notice. RSNs sparked to life in the 1980s," Bouris said. "It was a boon to the sports industry, selling inventory that was going unwatched aside from the live (in-person) opportunity."

The Cablevision contract was so valuable that when the Islanders were sold in 1998 for $195 million, $100 million was for the TV deal and $95 million was for the team.

Coinciding with the beginning of the first RSNs was another upstart that spurred the growth of cable: ESPN.

"The ingenious thing (ESPN) did was it would be paid for by every subscriber that paid for cable, ESPN was on the basic tier, and not placed on a sports tier," Bouris said. "(ESPN) peaked at 100 million subscribers. With a $7 per month fee, that was $700 million a month in fees."

This revenue model served both the networks and teams very well for many years. But consumers' habits are changing because of new technology and ways to consume media. YouTube launched in 2005. In 2007, Netflix began a streaming service.

Just as the internet unbundled local newspapers' monopolies by remaking advertising markets and allowing just about anyone to publish their niche interests online, television was now in the crosshairs.

Cable peaked at 100.5 million subscribers in 2013. That count fell to 84 million by the end of 2019 and to 74 million last year. The Wall Street research firm MoffettNathanson estimates cable erosion will continue at a rate of about 5% a year, and that there are another 26 million non-sports-loving households that are near-term threats to cut the cord.

But that rate of decline might be conservative. Comcast reported fourth-quarter earnings on Jan. 27 and said its cable subscriptions shrinkage is accelerating, down 7.9% in the fourth quarter of 2021, compared to a 6.4% loss in the fourth quarter of 2020, and 3.2% in 2019. That means the cable base could shrink to 50 million before the end of the decade, and it's not clear whether the industry can survive at that level. While cable still leads in hours spent watching television, streaming is gaining. MoffettNathanson forecasts that cable and streaming will be equal in terms of consumer usage by 2024.

Suddenly, that $700-million windfall ESPN received every month to pay for expensive national rights fees is drying up. The same goes for the RSNs and their local rights.

"It's been a golden goose," Bouris said of cable. "You remove cable TV from the scenario, and franchises are worth a fraction of what they are today, players make a fraction of their salaries. This boom has been going on for almost 30 years. But the vast majority of people that pay never watch. That's been the model."

According to a report in May from YouGov, a market research company that surveyed 3,800 adults, 47% of TV viewers in the U.S. are already cordless. Among those who still subscribe to cable, 44% plan to cut or pull back their cable subscriptions in 2022. In an updated YouGov survey in December, the number of respondents who said they were cordless jumped to 54%.

Younger consumers are leading the cord-cutting revolution, with 64% of adults between 18 and 34 reporting in December that they don't subscribe to linear cable. Of those under the age of 50, 65% said they stream six or more hours of live sports per week.

"Locally, regionally, teams need a new economic model," Rich Greenfield, a media analyst with LightShed Partners, told The Athletic last year.

As cord-cutting continues, cable distributors continue to pass on higher and higher costs to subscribers like Alexander. After all, the rights fees ESPN and the RSNs have paid for live sports aren't shrinking. Dave Warner, a hobbyist blogger who writes about the topic, estimated in 2017 that payments for ESPN's rights deals took up 63.3% of their carriage revenues, up from 52.5% just two years earlier. That percentage is only getting higher.

"For now, the bundle is broken," NBA commissioner Adam Silver said at the SBJ World Congress of Sports last year. Sixteen NBA teams air local games on Sinclair-owned Bally Sports regional stations.

"To me, it's pretty straightforward: people are living on their phones."

MLB commissioner Rob Manfred noted at the conference that Sinclair's RSNs are valued around $5 billion, which is a problem since Sinclair paid $9.6 billion - $8.2 billion of it financed with debt - to acquire them from Disney in 2019. Disney had to divest the networks in its deal to acquire 21st Century Fox.

"There's excessive leverage on that business," Manfred said of Sinclair's RSNs. "If you think about what they paid for it, how much debt they have on it, I mean, you think it's over 80%, it's a huge number."

Some media experts, like Sports Business Journal reporter John Ourand, believe predictions of Sinclair's demise may be exaggerated and that Sinclair's debt holders will be able to keep the company afloat as it transitions to the direct-to-consumer world. But if Sinclair gets too underwater with its debt and can't survive, suddenly a large portion of live sports inventory would be in flux.

Sinclair reported local sports media revenues of $759 million for the third quarter of 2021, up modestly from the same quarter a year earlier ($727 million). While revenues from cable subscription fees increased, ad dollars decreased. During the third-quarter conference call, Sinclair CEO Chris Ripley also reported that its RSNs operations had 12 months of liquidity as a buffer against the tides. But the word "churn" was used eight times on the call by Sinclair officials.

"What's the point of no return?" Bouris asked. "What (subscriber) number will have to be reached where RSNs will no longer support teams?"

Change is coming. Legacy media companies, leagues, and teams are searching for their profitable path. Team owners have always resisted new technology but eventually bought in and benefited from it. That's a possible outcome again, but the transition could be bumpy.

Travis Sawchik is theScore's senior baseball writer.

Part 2: Where we're going | Part 3: How it looks in Canada

HEADLINES

- U.S. shows offensive muscle in 15-1 win over Giants before WBC

- Profar suspended 162 games after 2nd positive PED test, out of WBC

- Report: Phillies' Rojas fails PED test, won't play in WBC for Dominicans

- World Baseball Classic odds: Who will challenge Team USA?

- World Baseball Classic preview: Everything you need to know