How a third major league introduced labor relations to owners and players

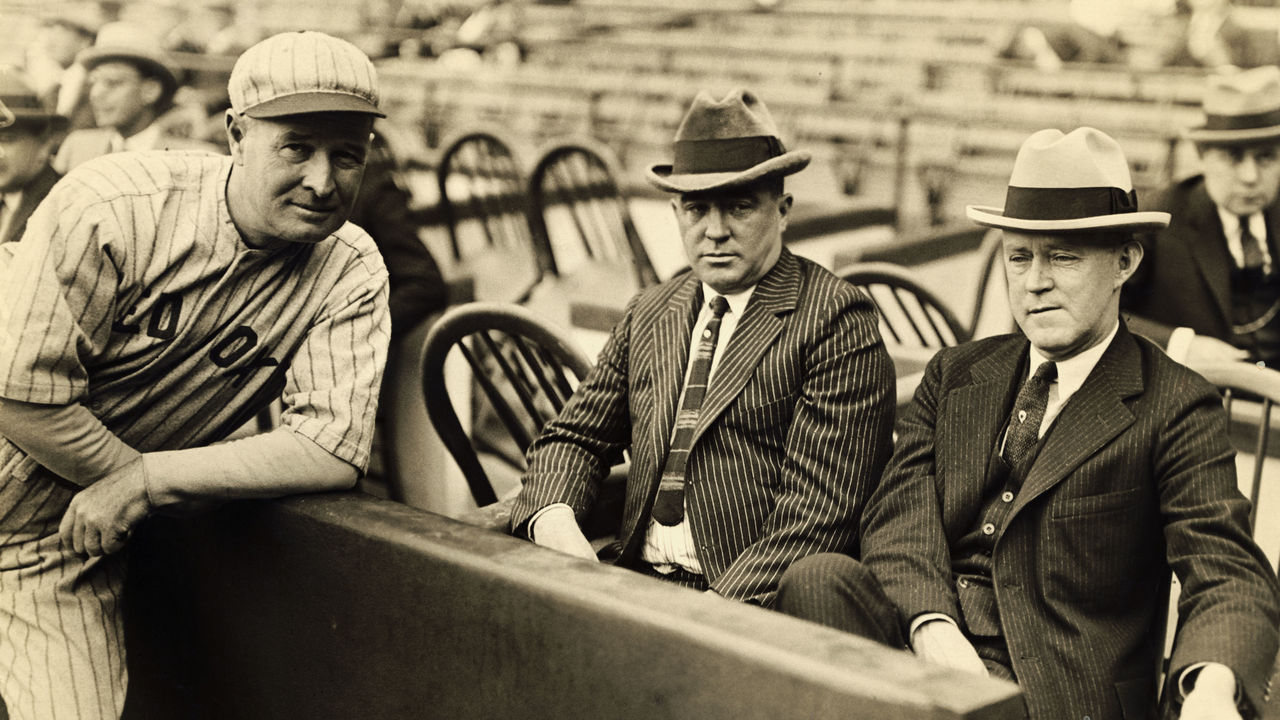

On Jan. 6, 1914, a train carrying New York lawyer Dave Fultz arrived in Cincinnati to negotiate with the National Commission, the three-member ruling body of professional baseball that included the presidents of the American and National Leagues.

Fultz's appearance was on behalf of players, something akin to their first union president. He was a baseball and football star at Brown, one of the school's first All-Americans. He played parts of seven seasons in the major leagues before retiring to get his law degree from Columbia.

He knew the gripes of players well, having experienced them himself. He heard from players occasionally as he practiced law in New York, which was home to three major-league teams at the time. He knew their complaints ranged from the relatively minor - like having to launder their own jerseys - to the significant: clubs could release injured players without pay. Fultz arrived in Cincinnati with a list of demands. He was threatening a strike, the first wide-scale labor stoppage in 20th-century sports, if they weren't met.

Scott Simkus, a baseball historian and author of "Outsider Baseball: The Weird World of Hardball on the Fringe, 1876-1950," said players then were subject to woeful workplace conditions by modern standards.

"You had to pay for your transportation when you got traded or sent down to the minors," Simkus said. "You didn't even get copies of your signed contracts. (Fultz) also wanted teams to commit to painting the center-field walls dark green, or dark color, for safety purposes so (batters) could see the pitch," instead of trying to find it amid a backdrop of advertising.

"The other thing that is really interesting is how they handled injuries back then. If a player got injured, they would pay your salary for two weeks, and then you were on your own. How about that? Even though you have a contract, and can't play anywhere else, if you cannot show up for work, 'we are not going to pay you.'"

Fultz was influenced by a 1912 event. During that American League season, Detroit star Ty Cobb was suspended for entering the stands at New York's Hilltop Park to fight a heckler, a disabled fan who'd lost a number of fingers in a printing press accident. Two days after the incident, Tigers players sat out, demanding Cobb's return. Detroit cobbled together a lineup of amateurs and lost 24-2 to the Athletics.

“If the players cannot have protection, we must protect ourselves,” the Tigers wrote in their grievance.

The Tigers and Cobb returned shortly thereafter, but the brief strike gave Fultz evidence to pursue something he was thinking about: if those Detroit Tigers could stand up collectively, maybe most players would have the resolve to organize.

On Sept. 6, 1912, Fultz founded the Baseball Players' Fraternity. It wasn't called a union, because a union had a negative connotation then, Simkus said, but it was the first time since the 1890 Players' League that players organized in any meaningful way. By the time Fultz stepped off the train in Cincinnati in early 1914, the Fraternity's membership included most major leaguers, nearly 400, and some 1,100 players in total. Unlike today's MLB Players Association, Fultz's fraternity also represented minor-league players.

He told all members that winter not to sign contracts with their clubs until he cut a deal. And he had leverage: there was a third major league coming.

In the summer of 1913, James Gilmore, a wealthy Chicago businessman, was golfing with his friend Eugene Pike, an investor in the Chicago franchise of the fledgling Federal League, Pike then sold Gilmore on a greater vision for the league, which made its debut as a six-team minor league a year earlier. Pike wanted it to become a major league.

Gilmore became president of the Federal League in August and recruited Charlie Weeghman, a Chicago restaurant entrepreneur who developed fast-service lunch counters, to become the majority owner of the Chicago club. They began recruiting other wealthy and relatively young businessmen. It would be akin to this era's tech and finance hotshots starting a league today.

"They had a bunch of rich weirdos that decided to start a third major league," Simkus said. "It was a bunch of guys in their late 30s and 40s with a ton of money. They said, 'Hey, let's start a baseball league.' How cool is that?"

The Federal League financiers included oil baron Harry Sinclair, who was later involved in the Teapot Dome scandal; George Ward of the Ward Baking Company, who became the owner of the Brooklyn Tip-Tops; and Phil Ball, a leader in the refrigeration industry. Ball's team would be the St. Louis Terriers.

They poured money into facilities. On March 4, 1914, Weeghman broke ground on a new stadium at the corner of Clark and Addison on the north side of Chicago, a ballpark that would signal the lofty ambitions he had for the club and the league. The first iteration of Weeghman Park opened, remarkably, two months later. Now known as Wrigley Field, it's what author Marc Okkonen describes as today's lone "silent monument" to the Federal League.

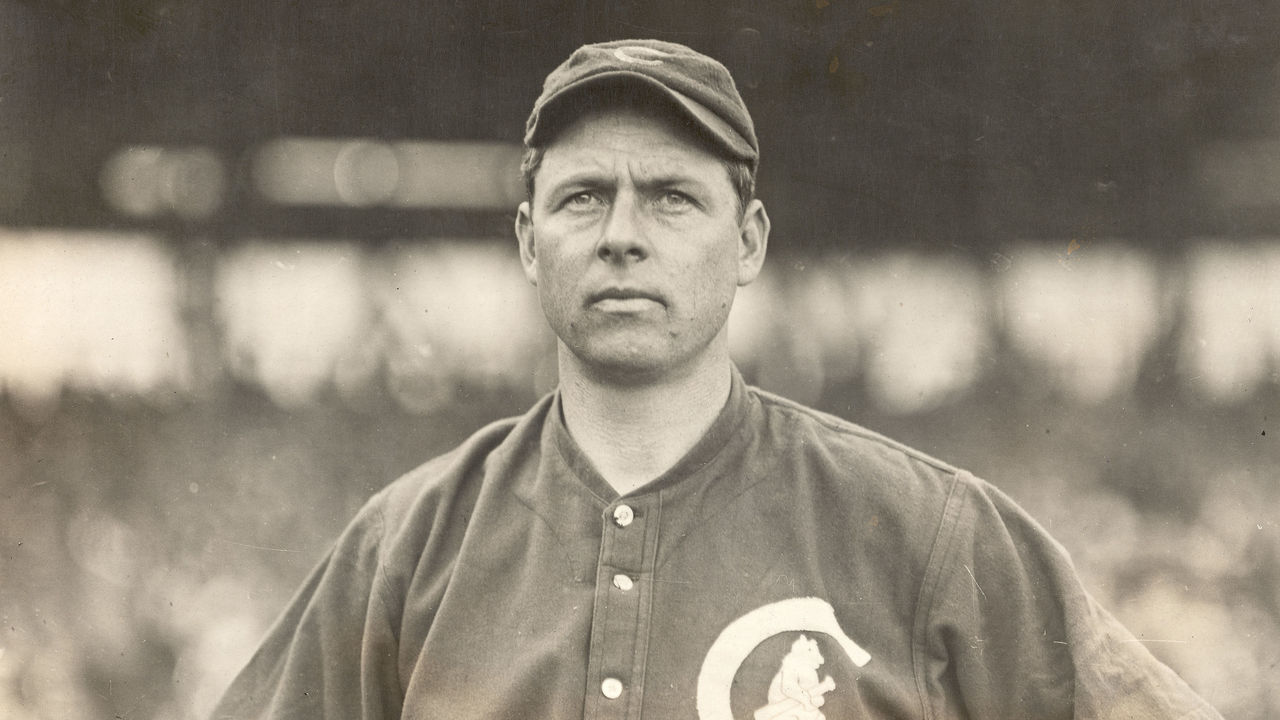

They also poured money into players. In December 1913, the Federal League shocked the major-league establishment when Weeghman signed long-time NL star Joe Tinker of the Cubs' famed Tinker-to-Evers-to-Chance infield trio. Tinker signed a three-year, $36,000 contract, a significant salary increase, and full payment was guaranteed by a bonding company in the event the Federal League folded.

"I'm a Federal Leaguer from now on," Tinker was quoted by The New York Times. "I'm a stockholder in the club, too."

That month, Ball's St. Louis club signed another player who was a Cubs' stalwart: Mordecai Brown, nicknamed "Three Finger" because of the loss of two fingers on his pitching hand in a farm-equipment accident in his youth. Brown was 37, but was coming off a year with Cincinnati in which he was again better than the league average, with a 113 ERA+. At the time, he had a 206-108 career record and a 1.89 ERA.

In the Dec. 23, 1913 edition of the Times, a story ran with a three-word headline: "Ban Johnson Worried."

"The defection of such a player as Tinker, at a time when he was the most prominent figure in baseball, has proved a stunning blow," the Times said. "Grave fears are entertained that other stars may follow."

In those days, players had few rights. There was no free agency and no salary arbitration, freedoms they wouldn't win until the 1970s. Players of the 1910s could hold out and refuse to play, or join semi-pro clubs that paid relatively well. Mike Donlin, a .333 career hitter (144 OPS+), played for Chicago-area semi-pro leagues for a couple of summers in the middle of his career while holding out. Those were his only options to try and create leverage until the Federal League.

On Jan. 14, after Fultz met with baseball's powers in Cincinnati, Cobb was courted and offered a five-year, $75,000 contract by the Federal League. He didn't leave, but it forced the Tigers to give him a hefty raise.

If you were a major leaguer playing on year-to-year contracts and didn't seek a raise at this time, you weren't doing it right.

"A lot of these guys were almost doubling their salaries just by using the Federal League as leverage," Simkus said.

Owners' claims from that period sound similar to today's.

In a Jan. 18, 1914 story headlined "Baseball Salaries Reach Top Mark," the Times reported: "Experienced baseball men say that the high salaries which are now being considered are absurd in contrast to the profits in baseball. … The result will be the loss of a great deal of money by club owners."

The Federal League was putting pressure on the establishment. In Cincinnati, Fultz took advantage.

"In 1914, Fultz made some headway," Simkus said. "One of the things (the National Commission) agreed to is they would pay guys throughout their contract. If you broke your leg in May, you would be paid for the whole season, which was a big win."

On the front page of San Jose's The Mercury News, on Jan. 28, 1914, it was reported that Fultz had secured a suitable deal. His order to withhold from signing contracts was withdrawn.

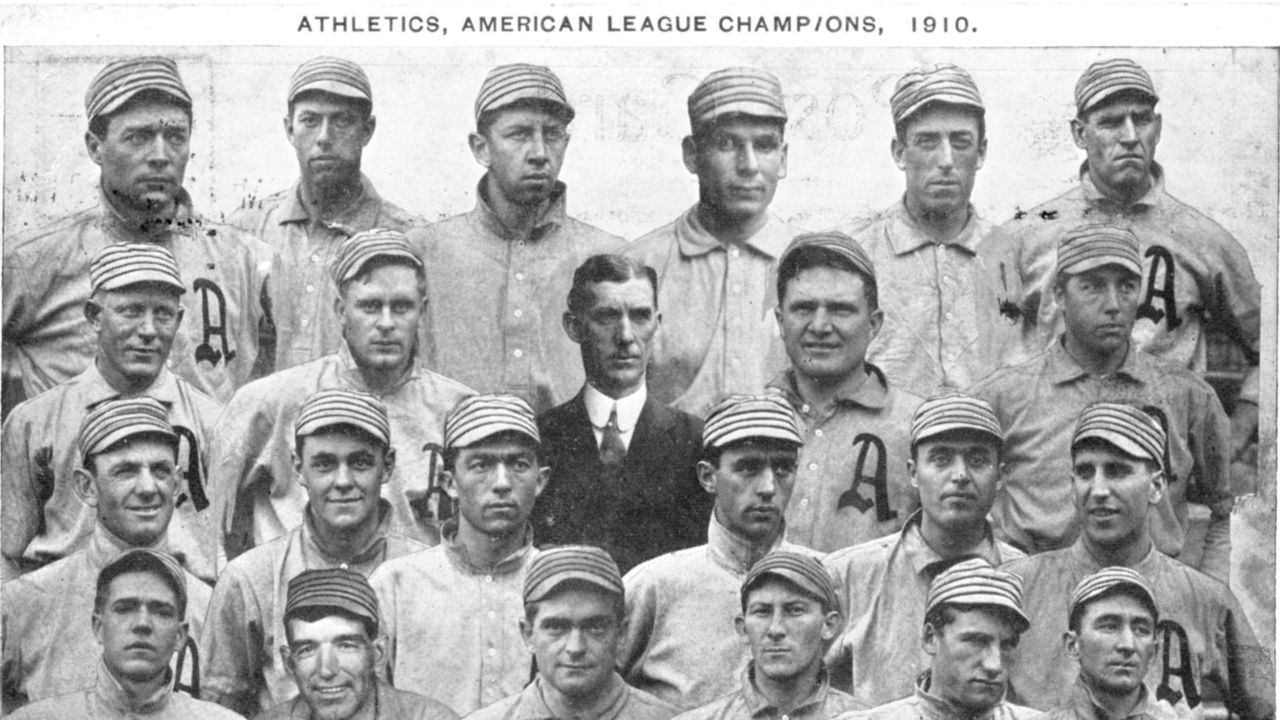

After its inaugural 1914 season as a major-league enterprise, the Federal League kept on its offensive, poaching a pair of future Hall of Fame pitchers from Connie Mack's Philadelphia Athletics.

The "outlaw" league, as it was described by AL and NL leaders, signed Charles Bender, who went 17-3 with a 2.26 ERA (115 ERA+) in 1914. Eddie Plank, a 38-year-old coming off a 15-7 season with a 2.81 ERA, also jumped ship.

"I wish him the best of luck," Mack said of Plank, according to the Milwaukee Sentinel. "I was through with him. He was after the money."

The 1914 A's won the AL pennant but were swept by the Boston Braves in the World Series. The 1915 A's lost 109 games and finished in last place, after Mack sold off other stars like 1914 AL MVP Eddie Collins in addition to his Federal League losses.

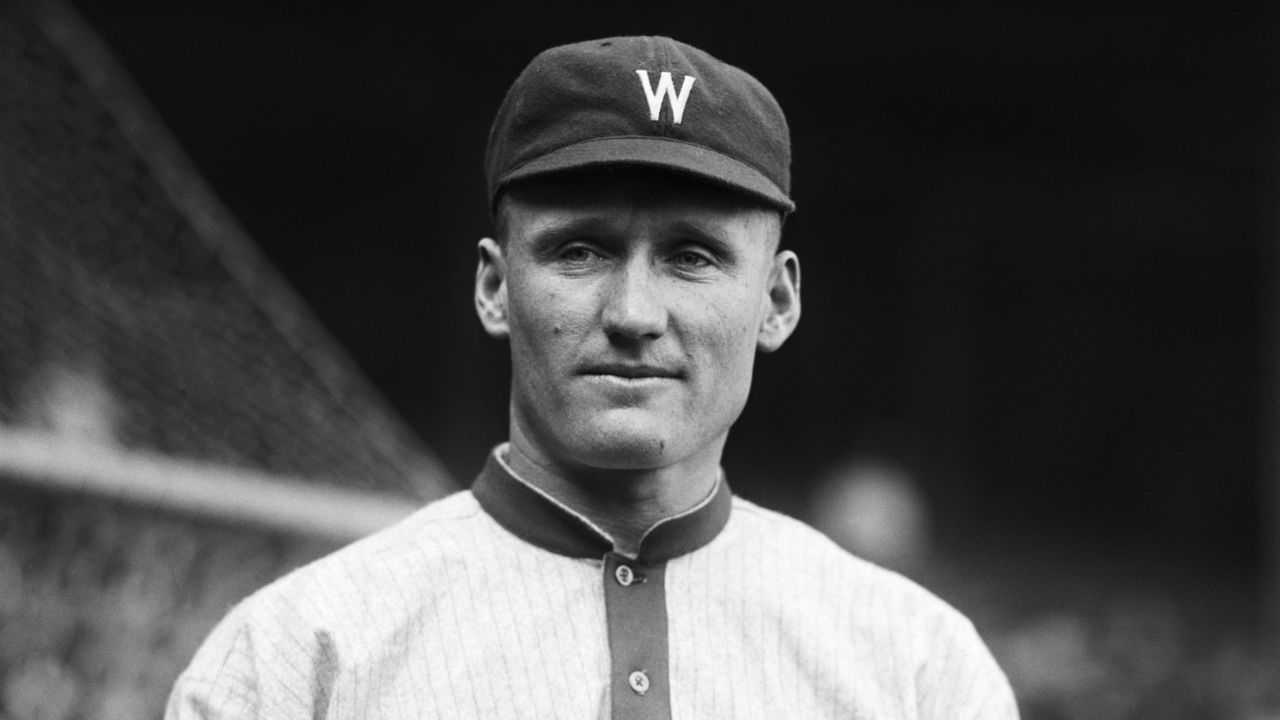

The Federal League didn't go after aging pitchers exclusively. It also went after the game's best: Washington Senators ace Walter Johnson.

Johnson agreed to a three-year deal with Weeghman's Chicago Whales, more than doubling his annual salary to $17,500 with a $6,000 bonus. But Washington owner Clark Griffith claimed the reserve clause prevented Johnson from leaving the Senators, and Johnson only backed out of the deal when Griffith agreed to match the bonus and double his salary to $12,500 a year.

Of the 286 players to play in the Federal League in 1914 and 1915, 172 had major-league experience, according to the Society of American Baseball Research. Of those, 71 would return to AL and NL clubs after the Federal League folded.

But most major stars remained in the AL and NL.

"They signed a number of major leaguers but generally aging veterans, or younger players buried on the depth chart looking for opportunity," Simkus said.

It was considered a major league for its two seasons, but it was probably better described as the best minor league, Simkus said.

Still, it eroded the market share of NL and AL clubs. While Federal League attendance records are spotty, combined attendance for the AL and NL fell from 6.35 million in 1913, an average of 5,152 fans per game, to 4.45 million in 1914 (3,456 per game) and 4.86 million in 1915 (3,907 per game). Attendance bounced back to 6.5 million in 1916 after the Federal League folded.

The Federal League made an impact before it ran out of cash. Can you imagine if today's MLB players decided to start their own league?

Frustrated with the recent lockout, Phillies star Bryce Harper last month posted a photo illustration of himself on Instagram in a Yomiuri Giants jersey.

He was also making an implicit point: players are the product.

What's the size of your jersey?🤣

— 読売巨人軍(ジャイアンツ) (@TokyoGiants) March 1, 2022

▶ https://t.co/YgSUH0sEp5#BryceHarper #ブライス・ハーパー@bryceharper3 #不屈 #巨人 #ジャイアンツ #giants #東京 #tokyo #野球 #プロ野球 #tokyogiants pic.twitter.com/jJW2yNcULa

The Federal League was ideal as leverage for players back then, but it would be all but impossible to attempt now. All today's players can do is coyly tap on the windows of Japanese or Korean leagues, which have limits on the number of foreign players.

Echoes of the Federal League have reverberated throughout sports in the 20th century. The American Basketball Association challenged the NBA from 1967 until a merger folder four teams into the NBA in 1976. The World Hockey Association went toe-to-toe with the NHL during its eight-season run from 1971-79 and also resulted in a merger. The USFL tried to come for the NFL in the early '80s but only managed three newsworthy seasons played during the NFL offseason.

Those upstart leagues provided players with alternative outlets for their labor and monetary competition for their services. The WHA lured Gordie Howe out of retirement at age 45 and paid Bobby Hull a $1-million signing bonus to play in Winnipeg. Wayne Gretzky, Mark Messier, and several other young players got their start in the WHA. The ABA enticed Rick Barry and Billy Cunningham from the NBA and launched the careers of Julius Erving, Spencer Haywood, Artis Gilmore, Dan Issel, Moses Malone, and George McGinnis. The USFL poached a few NFL names but also signed the Heisman Trophy winner for three straight seasons (Herschel Walker, Doug Flutie, and Mike Rozier).

Golf is having its Federal League moment right now, spearheaded by Greg Norman and backed, controversially, by Phil Mickelson.

There are fewer obstacles in golf because there are no player contracts, no need to build stadiums, and media rights would be relatively easy to sell if there were enough big names involved. What's missing are players willing to take the risk. Mickelson attempted to use the new loop to leverage concessions from the PGA TOUR but was sunk by some intemperate comments made to an author writing a biography of him.

"Look at what is going on in golf right now where you have a heavily bankrolled, Saudi-backed alternative tour being offered … (but) there are few risk-takers that are willing to do it," Ed Edmonds, a Notre Dame professor emeritus of law, said in an interview. "But most of the established stars, even if they agreed with Mickelson that the PGA has done some things against their interests, in the last (few weeks) you've seen almost all the top 10 players saying I'm staying with the PGA.

"(With the Saudi tour) you have the money interest. You don't have a venue problem - they can find golf courses for these guys to play on. They'll be able to establish some kind of media presence."

For the Federal League, the losses mounted through its second and final major-league season. It also lost one of its top bankrollers on Oct. 18, 1915, when Ward died of heart disease. An appraisal of his estate showed he lost a fortune in owning the Tip-Tops.

"Mr. Ward's total estate was appraised at $1,739,158.77. It was reported at the time of his death he was worth about $3,000,000, and the appraisal showed he would have been that rich had he not gone in for baseball," the Times reported.

Like many startups, the Federal League reached the end of its financial runway.

In December 1915, the remaining owners signed a peace treaty with the NL and AL. The Federal League agreed to disband, with the AL and NL paying out $600,000. As part of the settlement deal, Weeghman bought the Cubs, and Ball purchased the St. Louis Browns.

In January 1917, Fultz threatened another strike.

He believed clubs weren't fulfilling the Cincinnati agreement at the minor-league level. Fultz was again demanding all players withhold from signing contracts until conditions were met. But cracks formed in the player ranks. The fraternity expelled New York Giants pitcher Harry "Slim" Sallee for signing his contract that offseason.

The demands again included guaranteeing a player's salary should he become injured. Fultz also asked, again, for an "allowance to the players of traveling expense from their homes to club headquarters or their training compass."

NL president John Tener was quoted by the Times: "There is absolutely no moral basis for a strike on the part of our players."

With little leverage, Fultz called off the strike in February. Shortly thereafter, Tener and AL president Ban Johnson announced they would no longer deal with the fraternity.

Fultz no longer had the leverage to force the major leagues to meet his demands. Not only was there no Federal League, but more and more young Americans, including ballplayers, were traveling across the Atlantic to World War I's Western Front.

In 1917, MLB owners began to go back on their word not only to minor-league players but major leaguers, as well. After the season, Fultz said organized baseball viewed the Cincinnati agreement as nothing more than "a scrap of paper."

"They reversed their stance on the injury agreement and some of the other things," Simkus said. "(The owners said), 'We're not going to do it anymore. What are you going to do about it? Sue us?'"

And with that, the fraternity dissolved.

The fraternity marked the first time players stood up to AL and NL owners. The threat of a work stoppage, combined with players bolting to a start-up league, won the players concessions. The wins didn't last but they demonstrated the power of staying united, using leverage, and showing modern players what someday could be possible.

That wasn't the end of the Federal League's mark, though. On May 29, 1922, a U.S. Supreme Court ruling gave the major leagues another leg up, which was based on a Federal League lawsuit. Back in January 1915, the league's Baltimore club sued the American and National Leagues, alleging they were violating the Sherman Act, which prohibited monopolies from engaging in interstate commerce.

The Federal League's lasting legacy is that decision, which went against it. Baseball's antitrust exemption is celebrating its 100th birthday this year.

There wouldn't be another successful attempt to organize for nearly 50 years, when the MLBPA was recognized as a union in 1966.

In every labor fight, players face off against their well-heeled owners, and players are almost always at a disadvantage. Any sort of leverage can be fleeting. History repeats.

Reflecting on his research of the period, Simkus said: "You learn we don't ever change."

Travis Sawchik is theScore's senior baseball writer.