Baseball's new CBA is already failing the spirit of competition

What is immediately apparent about the new collective bargaining agreement is that it won't change teams' behavior. Those that want paltry payrolls, some in service of tanking, will continue to skimp without consequences.

Yes, there are new CBA measures that will tie extra draft picks to players whose service time is not manipulated by clubs. (Imagine an NFL or NBA team not starting its best rookies to avoid starting a service-time clock.)

Yes, the freshly minted deal includes a draft lottery for the top six spots so that final records no longer exactly match the draft order.

But those measures won't do enough to change the ingrained behavior of club owners and front offices. It's taken just days for some clubs to demonstrate their desire to clear the decks.

Chief among them are the Oakland Athletics and Cincinnati Reds, who have begun dismantling what were competitive teams last season.

Too many club owners, it seems, are not passionate about competing on the field. Too many owners are content to increase their operating margins and watch the rising tide lift the value of their franchises.

The biggest shortfall of the new CBA is that there is no change to how revenue sharing works, and there's no incentive to win tied to it. There's also no new regulation - like a salary floor - to compel owners to at least create a perception of a balanced playing field.

While this lack of spending might seem isolated to certain markets, there is a league-wide risk that it continues to compromise the game's overall health, making it more and more a regional game rather than a national one.

Consider the absurdity of what the Athletics and Reds are doing.

The A's won 97 games in 2019, won the AL West in the shortened 2020 season, and were competitive again last season, winning 86 games. Yet, they're tearing their club down, moving star first baseman Matt Olson to Atlanta, star third baseman Matt Chapman to Toronto, and 2021 Cy Young contender Chris Bassitt to the Mets in recent days.

Cincinnati finished above .500 in each of the last two years. The Reds' core was under club control for 2022. What have the Reds done since the end of last season?

- They waived Wade Miley, losing a competent major-league starting pitcher for nothing. He was a 2.9 WAR pitcher last year. He had one year and $10 million left on his deal.

- They traded starting catcher Tucker Barnhart to the Tigers, and one of their best starting pitchers, Sonny Gray, to the Minnesota Twins.

- On Monday, outfielder Jesse Winker, an excellent hitter, and Eugenio Suarez were shipped to Seattle.

- The Reds are all but certain to lose outfielder Nick Castellanos in free agency.

That's a deep-drive-to-left-field of an offseason.

The Reds claim they might jump back into free agency and keep top arms Luis Castillo and Tyler Mahle, according to Ken Rosenthal of The Athletic. Perhaps that's better to be seen first than be believed.

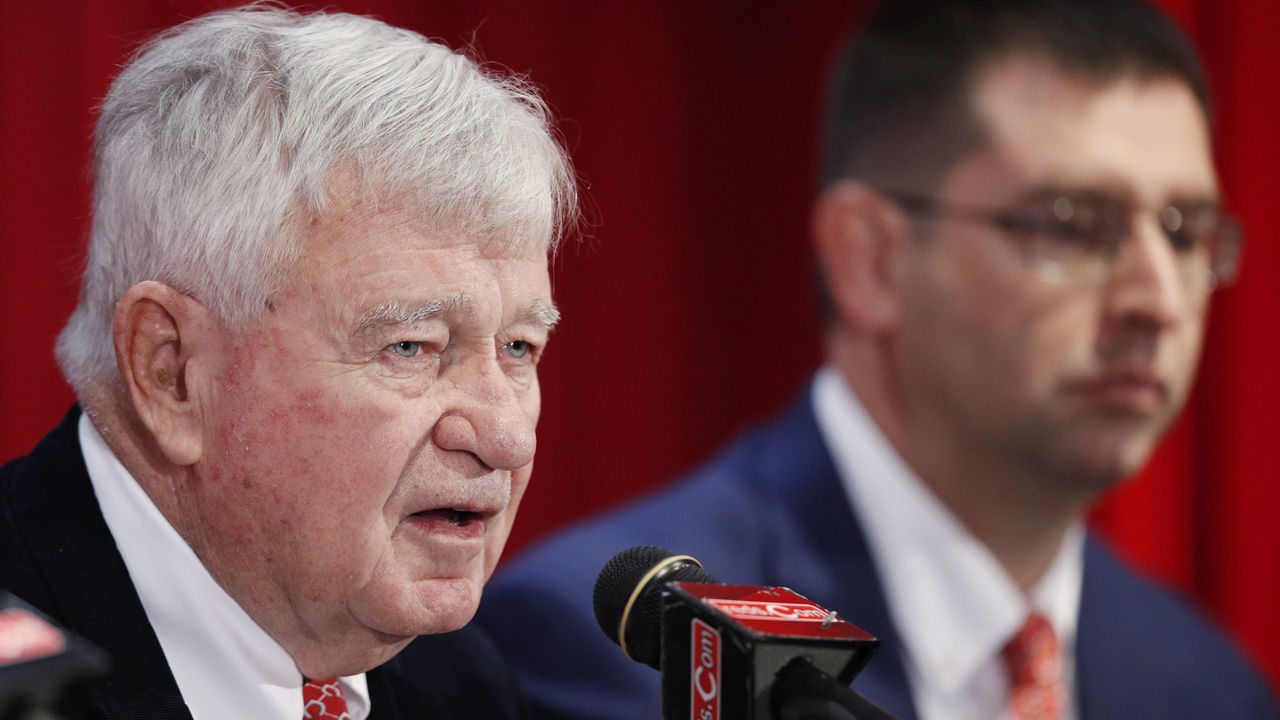

The Reds did add exciting young arms in Chase Petty and Brandon Williamson to go along with Hunter Greene and Nick Lodolo, but pitching prospects are risky, and no club can build completely from within. Will Reds owner Bob Castellini be willing to invest in the next core if he wasn't willing to invest in this one?

All that the Reds and A's have guaranteed this winter is that they won't be relevant in 2022, probably not in 2023, and perhaps much longer than that. Many fans will tune out, particularly in Oakland where a new ballpark is still just a plan and the threat of moving to Las Vegas remains.

How is that helpful in sustaining interest and gaining new fans for a sport that has by far the oldest average fan (57 years old) among North American contemporaries?

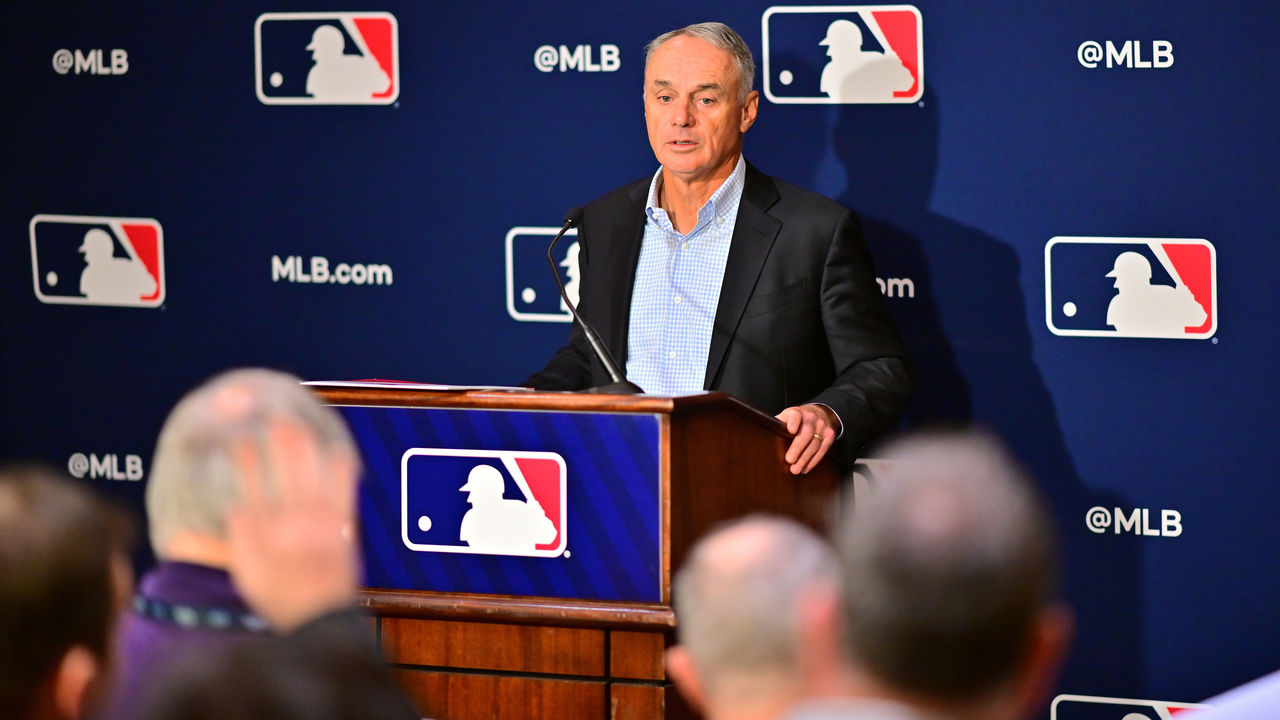

MLB commissioner Rob Manfred said something curious during the World Series of what was once called the national pastime: "We don't market our game on a nationwide basis."

So is MLB now simply a regional pastime? It's trending that way.

In its new TV arrangement with MLB beginning this year, ESPN will only broadcast 30 regular-season games - down 60% from last year.

Baseball is smart to begin its pivot to streaming with newly announced partnerships with Apple TV+ and Peacock (which is still being finalized). Streaming viewership will soon surpass that of traditional cable. The new streaming deals don't fully replace the revenue baseball lost when ESPN ditched its package of Monday and Wednesday night games this offseason. The shortfall is about $35 million, yet ESPN still gets access to the expanded postseason.

Much has been said in recent years about MLB's ability - or lack thereof - to gain the attention of new generations of fans. Baseball needs to pick up its game pace and is likely to introduce a pitch clock next year. It needs more action and more balls in play.

But I'd argue that a large part of the decline is the perception of an imbalanced financial playing field, with regular teardowns in some markets contributing to a lack of interest among fan bases. The new CBA addresses none of those issues.

It's true that baseball finds more parity in the postseason. Some argue that's a reason why it needs less payroll regulation, not more.

But that parity is merely due to the nature of the game. Unlike in the NBA where LeBron James touches the ball every possession, Mike Trout only bats four or five times a game. Unlike in the NFL where Patrick Mahomes starts every game, Jacob deGrom can only start once every five days.

And since baseball is less star-driven, it can be more difficult to turn a team around.

There's a reason the longest streak of losing seasons in North American pro sports history occurred in baseball (Pittsburgh Pirates, 1993-2012). And there's a reason, beyond there being fewer playoff berths than in other sports, that the longest current postseason drought also features a baseball team (Seattle Mariners, 2001).

While payroll is not everything - see: the Tampa Bay Rays - payrolls are loosely correlated to team success.

Small- and mid-payroll fan bases feel as if their teams are just glorified feeder systems for the New York Yankees and Los Angeles Dodgers.

The other major sports have cap-and-floor systems, of course. And beyond leveling the financial playing field, caps and floors help maintain interest in the sport. In such systems, teams are always forced to make trades and sign free agents to stay under caps or above floors. While these systems might not explain teams' success as much as many believe they do, they do help drive interest, locally and nationally.

Rarely are fan bases in Cincinnati, Oakland, Pittsburgh, and Cleveland in a position to be excited about a free-agent signing or trading for a well-known player in baseball. That's not true of other sports.

MLB's revenues have always been more regionally based than other sports due to the volume of games and the difference between local cable deals. In the recent CBAs, more revenues are shared. And yet payroll disparity in the luxury-tax era has grown, not shrunk. The system is not working. Owners are simpling depositing their revenue-sharing checks.

In 1995 and 1996 (the last years before the competitive balance tax) the top five MLB payrolls were a combined 2.4 times and 2.5 times greater than the lowest five, respectively.

In 2010, the gap was 3.3 times.

In 2021, the gap was 3.8 times.

In MLB, 48% of all clubs' net local revenue is placed into a pot and split among teams based upon a formula that results in moving money from larger market teams to smaller markets. Along with national media dollars, smaller market clubs are generally earning more than $100 million per year in shared revenue.

Yet, few of the receiving teams consider spending up to the CBT threshold level, which is now $230 million. Only nine teams overall have ever gone above the tax level.

Perhaps there was a glimmer last summer when the owners proposed a salary floor of $100 million tied to a $180-million initial CBT level. I argued then that a floor would be a long-term benefit for players. But the players were opposed to a lowering of the CBT level, so it never got off the ground.

The players' priorities were elsewhere this CBA cycle, rightfully focused on younger players and trying to increase the tax thresholds. There were some efforts to change the revenue-sharing system, but they were tabled.

At some point, I believe the MLBPA and its players will see the benefits of guaranteeing a share of baseball's revenues and having all owners meet a payroll floor.

Since its introduction, the luxury tax has headed toward being a more rigid cap without forcing owners to spend to a floor. That doesn't seem like a sustainable trajectory.

A floor ultimately is good for the greater majority of players and fans. It could grow the game - and revenue pie - for owners and players. Without one, we'll continue to see some teams do exactly what the A's and Reds are doing. We'll continue to see reasons for fan bases to check out, sometimes for years at a time.

The national pastime is becoming a regional pastime. It's a problem that is not going away, a problem being kicked down the road to be addressed on another day, in another CBA.

Travis Sawchik is theScore's senior baseball writer.

An earlier version of this story misstated how revenue sharing works. It has been corrected.