The long, steep hill to overcoming the yips

Steve Blass developed Steve Blass disease - what's known today as the "yips" - at the height of his powers in 1973. The worst part was the silence.

The Pittsburgh Pirates' ace, about to enter his ninth season in the majors, had just finished second in National League Cy Young voting. But in the spring of 1973, he lost the ability to throw a baseball across the plate. That season, he walked 84 batters in 88 innings, and led the NL with 12 hit batters.

On the road, he was heckled. But at home, at Three Rivers Stadium, the sound was different. When it was clear the issue wasn't going to be easily remedied, the fans would "go silent," he recalled.

"They were all rooting so hard for me and that was the toughest thing of all," Blass, now 80, told theScore. "They didn't boo me."

Blass never thought about mechanics, the muscle memory he'd built. Blass was always an "instinctive" pitcher, he said. But his instincts abandoned him at the age of 31.

He tried everything. He worked with sports psychologists at a time when it was taboo. He tried hypnosis and visualization techniques, too. Nothing worked.

His despair accumulated and "toward the end," as he describes it, he couldn't sleep. He would go out to the back patio of his suburban home in the rolling south hills of Pittsburgh and sit alone. More silence, save for cicadas chirping. It was a lonely fight. No one understood it, including Blass.

"I'd be out in my backyard at 4 o'clock with tears coming down my eyes. I knew I wasn't going to be a Pirate anymore," Blass said. "It was tough on our kids. The year before they were asking them for my autograph (at school), now they are telling them your father is a bum."

He returned in 1974. He didn't pitch until the 10th game, taking the mound at Wrigley Field for mop-up duty. In five innings, he allowed eight runs, walked seven, and threw a wild pitch. He never pitched in another major-league game.

Numerous baseball careers have been derailed by the condition, including those of Rick Ankiel, Mark Wohlers, Mackey Sasser, Chuck Knoblauch, and Pedro Alvarez.

This perplexing and remarkable loss of skill is not a baseball-only phenomenon. Golfer Tommy Armour coined the term "yips" in the middle of last century, describing it as "a brain spasm that impairs the short game." It derailed his career.

In the NBA, point guard Ben Simmons became a hesitant shooter last postseason. The yips? He didn't play this year. At the Winter Olympics, U.S. skier Mikaela Shiffrin - who owns 73 World Cup titles - couldn't stop falling down on the Beijing slopes. She never slips.

"I don't know what I'm supposed to fix, that's the frustrating thing," Shiffrin said, fighting back tears. "The last 15 years, everything I thought I knew about my own skiing and slalom and racing mentality … ." She paused. "Just processing a lot."

Sian Beilock is a cognitive scientist, the author of "Choke," and president of Barnard College in New York. She's researched the phenomenon extensively. She also experienced it herself as a goalkeeper in high school. During a tournament, she noticed a high-profile college coach show up to scout.

She became mechanical. She thought about her every move. By "being evaluated," her performance changed.

"It's a disruption in a well-learned skill that you could otherwise do on autopilot," said Beilock, who's also given a TED talk on the subject. "All of a sudden, something that is fairly easy or routine is not. … We are pretty good at doing lots of things. When you get nervous about something, one of the things you often try to do is monitor what is going on."

Her research includes a study of a college soccer team in which players dribbled a ball down the pitch but paid attention to which side of their foot was contacting the ball, an aspect of their performance they wouldn't normally notice consciously. She found players moved very slowly and were more error prone when asked to focus on that detail - what she calls "over-attention."

There's a better understanding of what the yips are today, but remedying it is another thing entirely. Solving the yips escapes many athletes, teams, and coaches. While baseball and other sports have made great advances in quantifying performance and data-driven player development, there are fewer breakthroughs in overcoming performance blocks like the yips. But Atlanta Braves pitcher Tyler Matzek and a former Navy SEAL have perhaps cracked the code.

When autopilot turns off

The day before the 2015 season opener in Milwaukee, the Colorado Rockies held live batting practice under the closed roof at Miller Park. When Matzek took the mound, his ability to throw a baseball completely unraveled. What was once an automatic process became a conscious, unnatural one.

The crippling affliction began innocently enough. He rolled an ankle in spring training and didn't think much of it. But shortly after, he began both overthrowing and short-hopping his throwing partners. On the mound, the issues worsened.

In an empty Miller Park, on the eve of the new season, Matzek couldn't throw a strike. He hit two teammates. He returned to the clubhouse and sat facing his locker.

"In front of my locker, I was tearing up. 'What is going on?' I had no idea," Matzek recalled during a spring conversation. "That was the true moment where I was like, 'There is something wrong. This is not right.'"

But he believes he understands what happened to him.

"Us human beings, we are our subconscious," Matzek said. "We stay in our subconscious mind 99% of the day. We think we make decisions all the time, but our subconscious is making decisions. Our conscious mind is hardly thinking about anything. It's about being in that subconscious mind as often as possible because that's our comfort zone.

"When I rolled my ankle it put every single pitching motion into a conscious mind, which is a very high-anxiety, high-stress, high-focused state to be in when you are doing that. I think a lot of negative things happen when you are in that mindset."

Matzek made the analogy to driving a car. Once mastered, it becomes second nature, so much so that people text and read - not that they should - while they operate 4,000-pound machines. They go on autopilot, albeit a dangerous version. Matzek, though, was reverting back to that beginner state.

"When I was first learning to drive a car, I was freaking out. I was hitting the gas, the brake," Matzek said. "There is so much going on. I'm overloaded. I'm stressed out. To try and pitch and be in that mindset, it's not going to work."

You might be able to relate to losing that sense of autopilot. I did.

I shared with Matzek that when I drive over the Skyway Bridge that spans Tampa Bay during spring training, I become more mechanical, more anxious. I don't like the height. I'm more aware of my surroundings, of how much pressure I'm applying on the accelerator, what my speed is, where I am in the lane. The driving becomes less fluid.

Perhaps I had the driving yips.

And my anxiety ratchets up before I reach the bridge itself. For Matzek, currently on the injured list with a shoulder strain, he began dreading going to the ballpark.

Beilock has employed brain imaging in her studies to understand what's at work.

"We looked at what is happening in the brain when people are getting ready for something that is stressful," she said. "This is really the emotional center of the brain. Areas of the brain that are involved in our pain response, sort of saying, 'Uh oh, there is this unexpected negative event coming.' … When you see the most neuro alarm signals in the head is that sort of anticipation of the 'what ifs.' That has consequences for how we perform."

After walking six Arizona batters in two innings at home on May 6, 2015, Matzek was demoted to Triple-A.

He walked 15 batters in 11 innings at Colorado Springs, and was then sent further down the ladder, to Low-A, where the dark cloud followed him.

The Rockies eventually released him after the 2016 season. In February 2017, the Chicago White Sox signed him to a minor-league deal, but released him in March.

Matzek was out of baseball.

He and his wife moved back home to Southern California. For several days, he lay in bed, paralyzed by anger and depression over this curse he couldn't shake.

Then the phone rang. It was his former Rockies teammate and battery partner Michael McKenry.

"'Hey man, I have a guy you need to meet,'" Matzek recalled McKenry saying. "'He'll fix you.'"

The physical manifestation

Jason Kuhn had big dreams vanish, too.

He was a pitcher at Middle Tennessee State, a top-25 ranked team in 2001, when the Blue Raiders made an NCAA Regional. He hoped to be drafted in 2002.

But the yips began during an intrasquad outing in his senior year. He walked the bases loaded, then walked in two runs.

In the only game he pitched that spring, he threw seven wild pitches - he believes it's still an NCAA record - and walked six. That was the end of his college pitching career.

For a time, he drank himself to sleep in his dorm.

"My life was hell on earth," he said.

He woke up one morning after drinking, peeled himself off the hallway carpet, and thought, "Is this going to define you?"

Looking back, he believes there was no one root cause. He went through challenging relationships with coaches. He grappled with anxiety like Matzek. More than anything, perhaps too much of his identity was tied up in being a baseball player. There were whispers that he was mentally weak.

"I just kinda thought I had gone crazy," Kuhn said. "I did what most people do: I attributed it to mental weakness because we don't know what else to attribute it to. But I never really believed that. I just didn't know what else to do with it."

Later, Kuhn would focus on the physical manifestation of the yips instead of the psychology of it, but first he had to eliminate a variable: that it was mental weakness.

He asked himself: what's the toughest thing one can do to test himself?

So he showed up to Coronado Island, across from downtown San Diego, in 2004 to attempt to join SEAL, the U.S. Navy's elite commando unit. Much of the motivation was tied to patriotic duty after Sept. 11, 2001, but he also wanted to prove to himself he wasn't mentally weak.

Becoming a SEAL is a year-long process. Few make it through the first stage, a month of basic training that culminates with "Hell Week."

Hell week begins Sunday morning at midnight and ends Friday afternoon. The SEAL hopefuls are pushed to the limits. They lay in the surf as the Pacific pounds them into hypothermia. Some panic and ring the bell, which is the way out. They swim grueling relay races. They carry rubber inflatable rafts above their heads wherever they go. They scale walls and climb ropes. Some break arms and legs. They're allowed to sleep a total of four hours during the week.

"Most people quit early, on Monday, during hell week," Kuhn said. "They quit because they are thinking six days down the road instead of six inches in front of their face.'"

Kuhn was close to quitting Monday, too.

He was in and out of hypothermia, from what he called "surf torture." He was ordered out of the water and an instructor began badgering him inches from his face.

"Everyone hates you, Jason. Why don't you quit. Just go over and ring the bell."

Nearly equidistant from where his team members were up the beach was a van with its back doors open. The quitting bell was there, in the back, and so were blankets, burritos, and coffee.

"I really wanted to go over there, I wanted relief from the pain," Kuhn said. "But I remember telling myself the bell is the same distance to where my boat is. So if I could get there, to the bell, I could get to the boat. I was like, 'Dude, just take one step.' I took one step in the right direction. Then another. Then I put the boat on my head. I started running down the beach. The blood flow comes back, you are not in hypothermia anymore."

He caught up to the team, lifted the boat over his head, and asked if they hated him.

"No, man," someone said. "They say that to everyone."

He and 19 others out of 135 who started made it through. Kuhn wasn't mentally weak. That's not what the yips were about, he reasoned. So what had happened to him?

In firearms training, SEALs often employ dry fire, meaning they don't use live ammunition. The practice is for safety. They're still working on grip, targeting, reloading - anything that can help make you a better shooter without an actual bullet. SEAL trainees were told by an instructor how shooters become more inaccurate when live ammunition is added.

"What happens is, rationally, they don't want to move the gun, they want the sights aligned, that's exactly what they tell themselves to do," Kuhn said. "But when they go to pull the trigger, that subconscious part of the brain says, 'Hey, there is an explosion taking place in your hands. Prepare for that.' And you flinch just a little bit. A little bit of flexion in your forearms or wrist or fingers and it moves the barrel off target. When I heard that, it was like the light was shining down from heaven - I was having an epiphany."

He now understood the mechanics of what happened to him when he was pitching: his body was trying to protect itself. It anticipated a threat. The result was an involuntary spasm.

Dave Owen in The New Yorker reported on a 2014 study comparing golfers with and without the yips. Aynsley Smith, a sports psychologist at the Mayo Clinic, was testing a theory that "the yips are on a 'continuum' with choking at one end and a category of neurological disorders called focal dystonias at the other." Focal dystonias are involuntary spasms of small muscles, in this case of the wrist and hands.

Smith and other researchers collected data, including from a wireless motion-capture device called the CyberGlove II, to measure wrist and hand movement. They found "yipping was characterized by the 'co-contraction' of groups of arm muscles that don’t ordinarily operate at the same time: one group that extends the wrist and one that flexes it."

This was what Kuhn experienced.

Kuhn served in the Middle East as a SEAL and later as a private contractor. When he returned to Tennessee as a civilian, he founded Stonewall Solutions, which helps clients build teams and grow leadership skills. He also returned with a potential cure for the yips.

Remission

Matzek was intrigued after McKenry's call.

McKenry, who also played at Middle Tennessee State, explained he met Kuhn while arranging a bachelor party for Andrew McCutchen, then a star for the Pirates. Kuhn took them to a shooting range, and ran them through some other insane drills.

Matzek tried everything to defeat his yips, but nothing worked. He agreed to speak to Kuhn, and eventually made his way to Tennessee to work with him and McKenry, who would assist.

He spent a week there. They met first at a shooting range on Day 1. Kuhn explained his spasm theory, dry rounds versus live. They talked about fear. Matzek said he felt it on the mound. A certain amount was good. Kuhn needed it to survive firefights as a SEAL, but too much was paralzying. They then traveled to a rolling plot of pasture land owned by a friend of Kuhn's south of Nashville for one specific geographic feature: a hill.

"I swear it was 45 degrees straight up," Matzek said. "A grass hill in a cow field, lumpy and terrible."

The task for Matzek was to scale the 150-foot hill as quickly as he could while throwing a medicine ball as he advanced. Every time Matzek threw the ball, it lost about half the distance rolling back to him.

An additional point of concern was added to Matzek's mind: at the base of the hill, McKenry was holding another medicine ball over his head while squatting. He had to hold that uncomfortable position until Matzek reached the top of the hill.

They began. A few minutes in, McKenry's body was shaking, trying to maintain the position. Matzek was gasping, heaving the ball as far as he could. They each ended up vomiting. Eventually, though, Matzek made it.

Kuhn watched and thought. "'Man, that guy is all heart and guts.' I wanted to build mental toughness and see where he was with it."

The hill was to teach Matzek something else about performance, too.

"The focus to motivate him going up that hill is kind of unique: you will reach a higher level of performance not just as a team, but also as an individual, by focusing more on your teammates than yourself or your own outcomes," Kuhn said.

Said Matzek: "I love McKenry. I don't want to see him in pain. … I can solve his pain by doing what I need to do. Instead of feeling sorry for myself, I have to push this up this hill.

"I think the biggest thing when I was going through (the yips) was I had a victim mindset that Jason helped me out of. 'Why me? Why me? Why me? Why is this going on?' Instead of just accepting it, what am I going to do about it?"

Matzek shed the victim mindset in working with Kuhn, who told Matzek his issue had nothing to do with mental toughness. That meant a lot to Matzek coming from an ex-SEAL.

After focusing on physical and mental toughness, they made their way to the place where Kuhn lost his ability to throw: Middle Tennessee State's Reese Smith Jr. Field.

It was time to pitch.

"I started doing anything and everything I could to see if we could get a relapse of the yips and also train him how to focus," Kuhn said.

As Matzek threw, Kuhn blared a siren. He played YouTube clips of play-by-play voices critical of his performance through a megaphone. McKenry found an old Matzek Rockies jersey and placed it in a visible spot in the dugout, his past haunting him.

Later, when Matzek returned to throw after a break, a few people started arriving at the field. This was a surprise to Matzek. Kuhn had called some friends and asked them to walk behind home plate to distract Matzek. Some sufferers of the yips can perform adequately when no one is watching. But when the lights come on, so do the yips.

Blass never had any problems in the bullpen, only in games.

In 2014, Pirates third baseman Pedro Alvarez caught the yips. He made 24 throwing errors in 95 starts. But he often made accurate throws in empty, pregame stadiums. He was out of a starting job in 2017 and out of the majors in 2019.

Author Malcolm Gladwell studied the phenomenons of panic versus choking - choking being a condition on the yips-related spectrum - in a New Yorker piece titled the "Art of Failure," published in 2000.

Wrote Gladwell: "Choking requires us to concern ourselves less with the performer and more with the situation in which the performance occurs. … Choking is about thinking too much. Panic is about thinking too little."

Kuhn even donned a helmet and stood in the batter's box, knowing that one thing that deeply bothered Matzek, that truly twisted his stomach, was hitting batters.

"What is performance? It's the ability to execute fundamentals under stress," Kuhn said.

As he threw, Kuhn gave Matzek only one cue to focus upon.

"The No. 1 thing is feeling that seam coming off your fingers," Kuhn said. "All the rest of it kind of flows from that initial concept. … The release is where the involuntary tension is, attacking and interrupting the throw."

Beilock agrees with the one-cue approach.

"It's almost something to distract you from the step-by-step details of what you are doing," she said. "The whole idea is if you are focused on that one thing, we only have so much attention, you can't focus on every little detail."

The feel of the seams is also the very end of throwing motion. Focusing on it allows the mind to revert to autopilot for everything leading up to that end point: the ball rolling off the fingertips.

Matzek was only throwing in the 80s that week. He wasn't finding the strike zone often. He was far from polished, or "cured," a term Kuhn hesitates to use. But he didn't hit Kuhn in the batter's box, either.

Matzek felt his anxiety recede that day. He took small steps and focused on them. Small goals: throw one strike, then two in a row, then five. He kept his focus on feeling the seam. He worked with Kuhn over the next six months, mostly remotely, and felt his mental health improving.

After a year out of professional baseball, Matzek attempted a comeback. He got a look with the Seattle Mariners in spring training but was cut. He then hooked up with the now-defunct Texas AirHogs of the independent American Association in 2018.

"I think when it first hit me that I could make it back, the mental stuff had come (a long way)," Matzek said. "It was that first bullpen in (Texas). I made a physical adjustment that matched the mental success I had. When I did that: 'Wow. This is it. I figured it out.'"

Matzek wasn't good in 2018, but he made it through the season. He was still wild, but walked his fewest batters per nine innings (6.7) at any stop since 2014 with the Rockies. He was throwing in the 90s again. He was striking out more than a batter per inning.

"For years, I was pounding, pounding, pounding that wall," Matzek said. "To do something so many times wrong, and to finally do it right. It was the best feeling you can possibly feel."

In 2019, the Arizona Diamondbacks signed him to a minor-league deal. He was released after pitching a couple of Double-A innings. He went back to the AirHogs, where he was excellent in 22 innings. The Braves picked him up that August. He struck out five in 2 1/3 innings over a couple appearances in Double-A. He was promoted to Triple-A, striking out 13 and walking five in 10 innings to close the season.

In 2020, more than five years after throwing his last major-league pitch, Matzek earned a spot on the Braves' big-league roster. He posted a 2.79 ERA and walked 10 in 29 innings during the shortened season.

At the end of the 2021 season, Matzek had the World Series trophy in his hands. He was a major bullpen contributor during the campaign and allowed only three runs in 15 2/3 postseason innings.

"I think the most important thing is you might be at the bottom one day, you might be in the World Series the next. It happened fast," Matzek said. "It got taken from me really fast, and it came back to me really fast."

Rinse, repeat

Matzek's not alone in making such a comeback after working with Kuhn.

Since the lefty's success story, a number of players have reached out to Kuhn; even a professional coach struggling with tossing batting practice sought his help.

Kuhn's working with 11 players today, ranging from minor leaguers to SEC players to lower-level guys. One of those college arms is Robert Synodi, a pitcher at Eastern Connecticut State, a Division III school.

Kuhn shared with him the same program he employed with Matzek, including a focus on feeling the seams at release. Synodi also began taking medication to address what he learned was significant anxiety.

Also helping Synodi: coming to peace with the idea he may never pitch again.

A common thread through many of these cases: the individual identifies as a baseball player and everything else comes second. When that existence is threatened, it exacerbates the issues.

Synodi paused our conversation to find and repeat exactly what Kuhn had told him. "'What I do does not define who I am, who I am defines what I do,'" he recited.

Said Kuhn: "This is new, but it's working. I really believe we have the solution here. I would love to see this problem that has been around for so long, with no real consistent solution, to have one, and have one that works across the board."

For anyone who can't avail themselves of Kuhn's help, Beilock offers one tip she shared in a New York Times guest essay about Mikaela Shiffrin's Olympic struggles.

"As I tell my students, remember to play your whole movie - not just the clip of your latest stumble on repeat," she wrote. "I hope that will lessen failure’s sticking power as they inevitably encounter a bombed exam, a botched job interview, a breakup. Those things won’t matter nearly as much as their willingness to try again."

Matzek didn't quit baseball. Blass didn't, either.

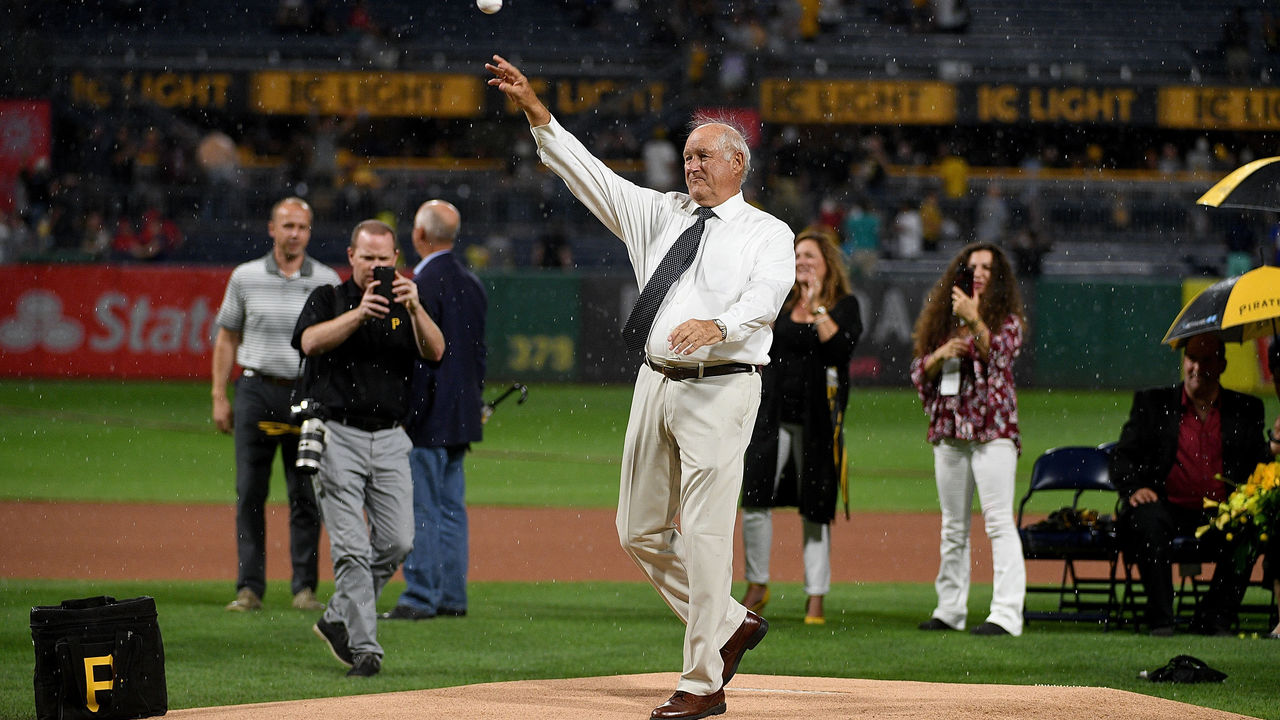

He became a broadcaster for the Pirates in 1983, working as a color analyst until he retired in 2019 as a revered local figure.

Blass didn't give up trying to beat the yips, either, long after his playing career.

In the early 2000s, he got a call from clinical sports psychologist Richard Crowley, who was looking for a way to reach Wohlers, who was suffering from the yips with the Braves. Crowley wondered if he could help Blass. He focused on visualization and relieving self-blame. Blass tinkered and felt he made some progress, but for a long time didn't test his arm in a competitive setting.

Blass was then a regular participant in the Pirates' fantasy camps each spring, where fans - mostly middle-aged men - pay to play in games with former major leaguers at the team's complex in Florida. But Blass never pitched in these games - not until January 2005.

One camper was riding Blass, then 62, that spring.

"He was saying, 'I wish you could pitch in these games, I'd rip your ass,'" Blass recalled.

Blass finally had enough and asked for the ball one morning. He pitched eight shutout innings at age 62. Yeah, it wasn't against major leaguers, but he walked only one. He was throwing strikes.

"I have no thoughts for a comeback," Blass quipped to Sports Illustrated, "but I felt ecstatic."

Blass proved he could overcome it.

He jokes he should have a 1-800 number for all the times he was called by pitchers - athletes of any kind, really - suffering from the yips. He regretted not having an answer, but he laid out a path.

"All I can tell you is: don't quit," Blass said. "It's not like it's not in there. You were good. Something might fall into place. But if you quit, you'll never find out."

Travis Sawchik is theScore's senior baseball writer.