To dream the impossible dream - and then decide it's time to let it go

Doug Deeds thought you could see his heartbeat pounding through his Reno Aces jersey.

The Arizona Diamondbacks' Triple-A affiliate had just completed its final game of the 2010 season in Salt Lake City, when the Aces outfielder was summoned into manager Brett Butler's office.

Deeds, then in his ninth professional baseball season, was coming off his best year as a pro. He finished with a .302 average. He was a Pacific Coast League All-Star. He knew this was the time of year when it was most likely to get called up, when major-league rosters expanded in September. The Diamondbacks weren't playing meaningful games, perhaps boosting his chances.

He knew this was how so many players received the news that the dream they chased since they were kids was about to come true. Despite being a .293 career hitter in the minors, he'd never received the call.

"God, this is what it feels like," Deeds recalled thinking as he sprung from the chair in front of his locker.

He floated across the clubhouse to the manager's office, taking a seat across from Butler, who everyone called "Bugsy," a nickname pitcher Mike Krukow pinned on him years earlier, saying the fedora Butler often wore made him look like a 1920s gangster.

"You had a great year, and I love ya, and I want you to come back and sign back with us," Deeds recalled Butler saying.

Deeds paused before answering.

"I said, 'Yeah, sure, Bugsy.'"

Deeds turned to the other former major leaguer in the room, hitting coach Rick Burleson, who couldn't bear to make eye contact with Deeds.

His heart sank.

"It was like a scene out of 'Bull Durham,'" said Deeds, who trained his focus back on Butler. "Bugsy, you're not calling me up, are you?"

"Nah, Deeder," he said. "I wish I could, but it's not up to me."

Butler rose and hugged Deeds. They knew time was against him. At 29, he was already 2.2 years older than the average PCL player that season.

Deeds wasn't your average career minor leaguer. There have been 246 players who compiled more than 4,000 plate appearances in affiliated and independent leagues since 1948 and played at least 10 years without reaching the majors, and among that cohort, Deeds' career .838 minor-league OPS (.368 OBP, .470 SLG) ranks 15th, according to data provided by Baseball Reference. His OPS ranks first among such players who started their careers this century.

He's one of 1,420 minor leaguers since 1891 to reach 4,000 plate appearances and never play in the majors.

I hadn't spoken to Deeds in some 20 years, after we both attended Ohio State. Back in 2002, I was writing for the campus newspaper and Deeds was a star on the baseball team. His left-handed swing helped him better teammate Nick Swisher in OPS and home runs. Swisher was the 16th player taken in the first round that summer, featured in the book "Moneyball," and went on to play 12 seasons in the majors. Deeds was selected 272nd that year, a ninth-rounder to Minnesota.

While researching a piece on the "Moneyball" draft this summer, I wondered what became of Deeds. What was it like to get so close to a dream and not reach it? Why do players like him keep chasing it? How do they decide to stop? Do we all hang on too long?

Anthony Medrano ranks second among 21st-century players in minor-league plate appearances (5,712) without reaching the majors.

Medrano was close, too.

Cleveland ended its 2002 spring with an exhibition game against Los Angeles at Dodger Stadium before opening the season in Anaheim. Cleveland had injury concerns as Opening Day approached, and Medrano traveled with the club as insurance. Entering his 10th year of pro ball, there he was in a major-league clubhouse on the eve of a new season.

"I was thinking, 'Man, I have a chance to make this team,'" Medrano said. "Even to have a cup of coffee in the big leagues, it would have been something that fulfilled everything."

But the next day, he was given a plane ticket to meet the Triple-A team in Buffalo. He spent 14 years in the minors, and parts of nine seasons in Triple-A.

Corey Smith accumulated the most affiliated minor-league plate appearances without reaching the majors of anyone to play this century: 5,835. He logged another 1,928 in independent baseball and the Mexican League.

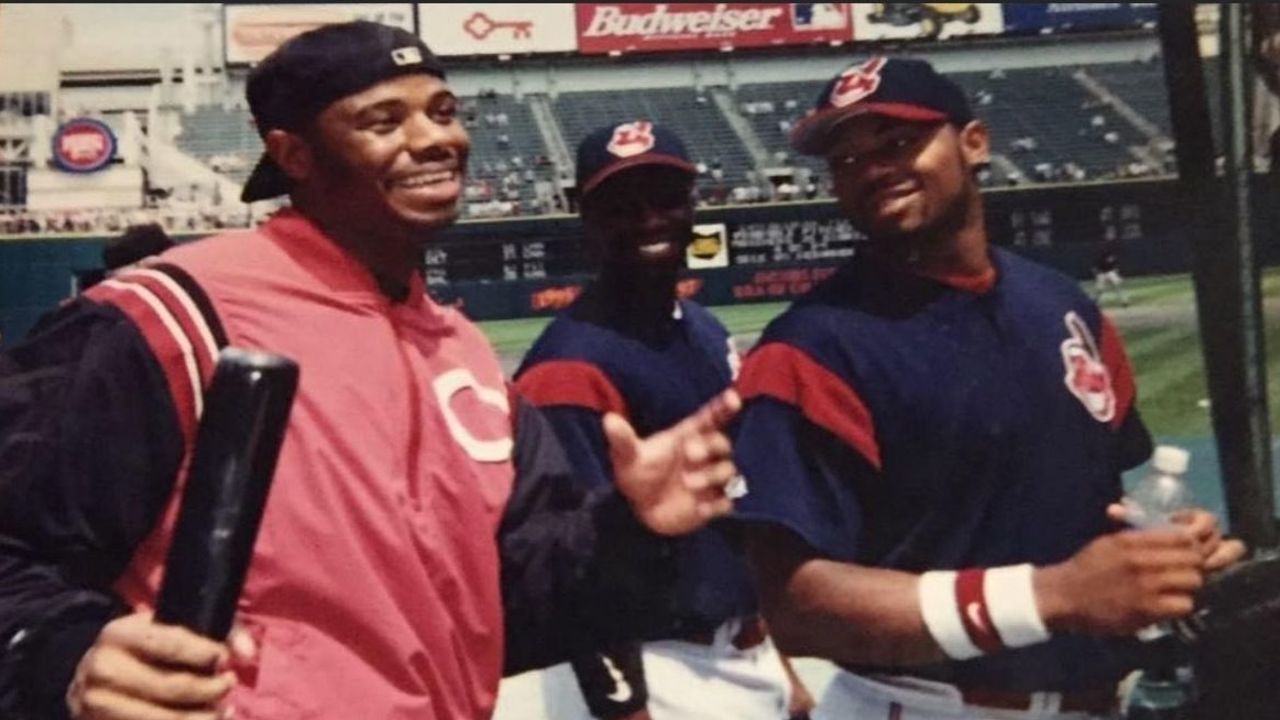

He was tantalizingly close to his dream just a few days into his career. Shortly after being selected in the first round of the 2000 draft, 26th overall, Cleveland flew him to town. He met with the media, toured the clubhouse, and took batting practice with the team. The Cincinnati Reds and Ken Griffey Jr. were in town.

As Cleveland neared the end of batting practice, Griffey and the Reds began to make their way around the batting cage. Griffey approached Smith.

"He was like, 'Welcome, kid.' He wished me luck," said Smith, who stayed on the field to watch Griffey hit. "He said he was going to go 'around the world.' His last round of BP, he hit a home run to left field, he hit a home run to center, and a home run to right field. And then went back around.

"I thought it was the beginning of this wonderful career," Smith said.

Hanging on

All three of them held on, hoping to become like 30-year-old Washington Nationals rookie Joey Meneses.

After spending 12 years in the minors, totaling nearly 5,550 plate appearances, Meneses reached the majors this year after Juan Soto and Josh Bell were traded to San Diego. Meneses hit 12 home runs in his first 49 games.

As they neared 30, maybe, just maybe, they could be like Mike Hessman, who recorded 250 major-league plate appearances over parts of five seasons. Hessman got his first call-up to Atlanta in his eighth pro season and played four more full seasons after his final call-up by Detroit in 2010. In 18 minor-league seasons, he compiled 7,540 plate appearances.

A few days into 2015 spring training, Hessman was approached by a couple of teammates in the Tigers minor-league clubhouse.

"They're like, 'Hess, you need 12 more,'" he recalled.

"Twelve more what?" Hessman asked.

"Home runs!" they said. "To be the all-time guy."

In Triple-A that year, at age 37, he was more than 10 years older than the average International League player. He hadn't played in a major-league game in five seasons, but on Aug. 3, 2015, he hit his 433rd minor-league home run, surpassing Buzz Arlett's record.

Hessman is now the Tigers' assistant hitting coach. He's seen people leave the game, regret it, and try to get back in. He saw them fail and become bitter. He didn't want that.

"I would never tell someone to stop chasing their dreams," Hessman said. "I didn't keep playing for the records. I was trying to get back to the big leagues one more time."

They are the outlier cases. Of course, anyone who reaches the majors is an outlier.

All time, there are 22,849 major-league players in Baseball Reference's database. Compare that to 226,179 to play in professional baseball at any level in North America, according to their records. (The minor-league record is incomplete prior to 1950, however.)

Smith hung on for so long in part because he was sure he was good enough. He was Baseball America's 73rd-ranked prospect in 2002, ranking second in the organization. He hung on because there's nothing better than playing, he said.

"The camaraderie you get in the locker room," he said. "The adrenaline of playing the game. You can't compare it to anything. … I wish I was still playing."

Deeds found more joy in the pro game later in his 20s, after being traded by the Twins. He joined the Chicago Cubs organization beginning in his age 27 season in 2008.

"From that point on, I didn't stress out about the 0-for-3s," Deeds said. "It wasn't until I let go some of the pressure of performing, just let it happen, that it made me realize how close I was. It became a chase to get to the big leagues, and chase down a childhood dream."

They also kept playing because they didn't have clear Plan Bs.

Even as he played into his late 20s, Medrano wasn't yet thinking about he and his wife's lack of savings, or what he was going to do after his playing career. To get by, he worked every offseason in the warehouse of a heating and cooling parts supplier in Kansas City. Minor-league baseball is seasonal work, after all.

"My mindset was, 'Hey, you gotta go out there and chase your dream,'" Medrano said. "Not having a college education … I didn't have anything else lined up. To be honest with you, (life after baseball) wasn't top of mind."

Deeds worked every offseason, too.

"You are so hyper focused on training, getting ready for next year, thinking about the what-ifs for the season to come, and how intoxicating that is," Deeds said. "It's like you put everything on hold outside of that."

Most of us hang on too long.

That's what Christopher Olivola, a Carnegie Mellon University professor who studies judgment and decision-making, told me.

He said human beings are poor managers of the economic concept of sunk costs.

"A baseball player who has put their own blood, sweat, and tears, and time and money into a baseball career, they are the ones who have made the investment. There's the sunk cost," Olivola said. "You want to honor your own past investments. You don't want all that time and money you put in to go to waste. But that in itself is irrational, because, if it's sunk, it's already gone. There's no getting it back.

"(With any sunk cost) where you're forcing yourself to do something that is not fun, or unlikely to succeed, that isn't going to bring the investment back. ... But we have this psychological feeling where, 'Oh, if I can just make it.'"

Studies show all animal species demonstrate some form of mismanaging sunk costs, he said, but we as humans add cultural layers.

We value perseverance as a culture - and in many cases for good reason - but sometimes we do so irrationally. We also worry what others will think if we quit, he said.

In her new book, "Quit: The Power of Knowing When to Walk Away," author and professional poker player Annie Duke notes regular, rational quitting at the poker table is what separates amateurs from pros. And in explaining sunk-cost effects, she wrote a rational actor "would consider only the future costs and benefits in deciding whether to continue with a course of action."

"Freakonomics" co-author Steven Levitt believed little was known about whether people make good choices when facing important, life-altering decisions. Such decision-making is difficult for economists to study. Most decision-making studies involved relatively low stakes, he noted.

Levitt came up with a clever idea. He announced he was seeking people who were on the fence with an important decision. He rounded up 20,000 participants, an effort helped by the following from his best-selling book. To be involved in his experiment, there was one catch: one had to agree to be bound to the result of a coin flip. One side of the coin ruled you stay, the other dictated you move on.

Levitt followed up every few months and had his participants answer survey questions. What did he find?

"Those who report making a change in follow-up surveys are substantially happier than those who do not make a change," he wrote in a 2016 paper published by the National Bureau of Economic Research. "This is true for virtually every question asked both two months and six months later. …

"This finding is inconsistent with expected utility theory; those who are on the margin should, on average, be equally well off regardless of the decision."

But they weren't.

Levitt concluded: "If the results are correct, then admonitions such as 'winners never quit and quitters never win,' while well-meaning, may actually be extremely poor advice."

Moving on

Sept. 3, 2012 marked the last game of Deeds' playing career. He was with the Salt Lake City Bees, the Angels' Triple-A affiliate, which finished the season at home on a sun-soaked Sunday afternoon.

He knew it was his last game. He grappled with it in spring training, now in his age-31 campaign. Unless he got a call to The Show, this was it.

There were faster, stronger prospects showing up in camp each spring. He was now 4.2 years older than the average PCL player.

"You start looking around and know how fast you are, or are not, and you know how your body feels," Deeds said. "Taking in all of the noise, and realizing where I was career-wise, the chances of me getting that chance were so slim. Even if I closed in on a .300 average, it was highly unlikely that that big-league call-up was going to happen."

Friends were disappearing, too.

One day in camp that March, Deeds returned to his locker after a spring road contest to find a game bat that his best friend on the team, Drew Macias, placed upright at the base of Deeds' stall. Macias was released while Deeds was playing, and the bat was Macias' goodbye gift. He'd already cleared out his locker and was on a flight back home.

"I also wanted to start the clock on that next chapter. And the next chapter is crawling out of the debt that baseball brought to you," Deeds said. "Let's get out now and be on better financial footing five, six years from that point."

But he'd wanted to "soak up" one last summer as a pro baseball player. He knew he was going to miss it. And he could still hit.

Deeds went 5-for-5 in his last game. His wife and his best friend were there to take in the final act.

Afterward in the clubhouse, he found himself not wanting to take off his jersey. He lingered at his locker for longer than usual, and the emotions flooded in.

"Every baseball player will have that moment where they were sitting in their locker one last time," Deeds said. "It took awhile to get that thing off and throw it in the laundry bin. It was tough. It was really tough."

Salt Lake manager Keith Johnson called him to his office.

"My God, are you really going to call it quits?" Johnson asked. He'd been in the same boat; Johnson had seven major-league plate appearances against 4,981 in the minors.

"We are going to call it quits," said Deeds, who hit .292 in his final season. "Unless you are sending me to some place."

He wasn't. Another hug.

Deeds cleaned out his locker and he and his wife headed east that same evening. Their Honda Accord barely made it through the Rockies on that five-day trip back home to Columbus. Two weeks later, he was in business school at Ohio State, working on finishing his degree.

"Once you're all-in, you're in," Deeds said, "and once you have one foot out, you have to be all the way out. That can be a miserable season if you're there, 50-50."

Deeds chose to end it. Medrano, like so many players, had the decision made for him.

In 2005, the Phillies asked Medrano if he'd be interested in coaching. Maybe that was a sign. But he wanted to give the dream one more chance. With New Orleans, the Nationals' Triple-A team in 2006, Medrano was 4.2 years older than the league's average player.

In the middle of May, after hitting a single to right, Medrano, then 31, slid hard into second base to break up a double play. He hurt his knee.

"Your mind goes everywhere," Medrano said. "How am I going to support the family?"

He had three kids, a wife, a mortgage, and a diploma from Jordan High School in Long Beach, California, from where the Blue Jays drafted him in the second round in 1993.

That offseason, a call from Cleveland came, but it was to coach, not play.

"Everyone has their own situation. If you don't have kids or a family, it's easy to keep chasing that dream," Medrano said. "(The decision) has to come from within. You see a lot of players that played in the big leagues and are still playing independent ball. Some people can't let go."

The game can be unfair. It wore on Smith.

He was certain he was the best player to fill a void on a major-league roster at times, but 40-man roster machinations and economics worked against him, he said.

"You don't lead the league in home runs and go back to the same league," he said of the 2008 Texas League. "I did."

He still remembers the names of players called up instead of him.

"It starts to get to where everything is stacked up against you," Smith said. "You keep grinding but eventually the fight comes out of you."

He finished his career with 172 home runs and a .259 average. After a couple years in independent ball, he opened a baseball facility, Upper Deck Elite Academy in New Jersey, following the 2014 season.

"I used to watch (MLB), but I don't anymore," Smith said. "There are guys that are still playing that I played with, or against, that I outplayed.

"It's painful."

The costs

There are costs to chasing this dream.

Minor-league pay is notoriously low, though perhaps that will change with minor leaguers agreeing to unionize.

Deeds signed for $90,000 as a redshirt sophomore, but his regular wages as a baseball player were cash-flow negative for most of his career.

"It carried me through a few years," Deeds said of his bonus. "My wife was the breadwinner, working at the mall, at Sephora. That kinda gives you an idea. You don’t make any money."

Smith signed for big money: $1,375,000. But about half of that bonus went to taxes and agent fees. Fifteen years in the minors chipped away at what he saved.

"It only lasted so long because we didn't make much," Smith said.

The costs go beyond the lack of pay.

During his final season, Deeds' parents traveled to Nashville to watch him play one last time. It was the closest PCL park to their home in Columbus.

His dad tracked all of his box scores, and listened to so many late-night internet broadcasts through minor-league team websites. For so many years, Deeds' father studied who was ahead of his son on organizational depth charts and how they were performing. Deeds knew about it, but tried to avoid the details.

As Deeds walked off the field between innings, he found his parents in the crowd.

"I look up in the stands, walking up to the dugout. I don't know if my dad could recognize who I was," Deeds said. "He was trying to squint, and point me out, and it hit me like a ton of bricks: My dad had aged so much in those 10 years, and I had missed so much. I have no regrets about making that choice (to play), but that was probably the toughest thing, that realization of how much life had changed since I had been away."

Olivola, the Carnegie Mellon professor, has identified another type of sunk cost in his research, what he calls interpersonal sunk-cost effect.

"In the context of baseball, you could imagine for some of these guys it's not just them who made sacrifices, maybe it's their families spending time, money invested in them, giving up things so they could afford to chase their dreams," Olivola said. "So now if they quit on their dream, not only are they betraying their younger self, all the work they put in, but they feel they are betraying potentially their parents."

It's not just a concept to Deeds.

"They wanted it just as much as I did," he said. "You kinda felt the weight of more than just yourself when you made the choice to step away and retire."

Medrano is a second-generation U.S. citizen. His dad crossed the Mexican border in search of a better life and settled in L.A., where he worked as a welder. His dad and his brothers loved baseball. They all played on a Sunday league team - his dad still plays - and Medrano and his cousins would play parallel games. Baseball was the dream for him and his family, too.

There were costs beyond finances for Smith, as well.

After he was released midseason by the White Sox from Double-A Birmingham in 2012, he made his way to play in Monclova, Mexico, more than 2,000 miles from home, where he had a newborn daughter.

When his wife brought his daughter to visit, his heart sank.

"She didn't recognize me," Smith said.

That offseason he joined an independent team in Somerset, New Jersey, 20 minutes from home, and never returned to affiliated baseball.

The one-inning dilemma

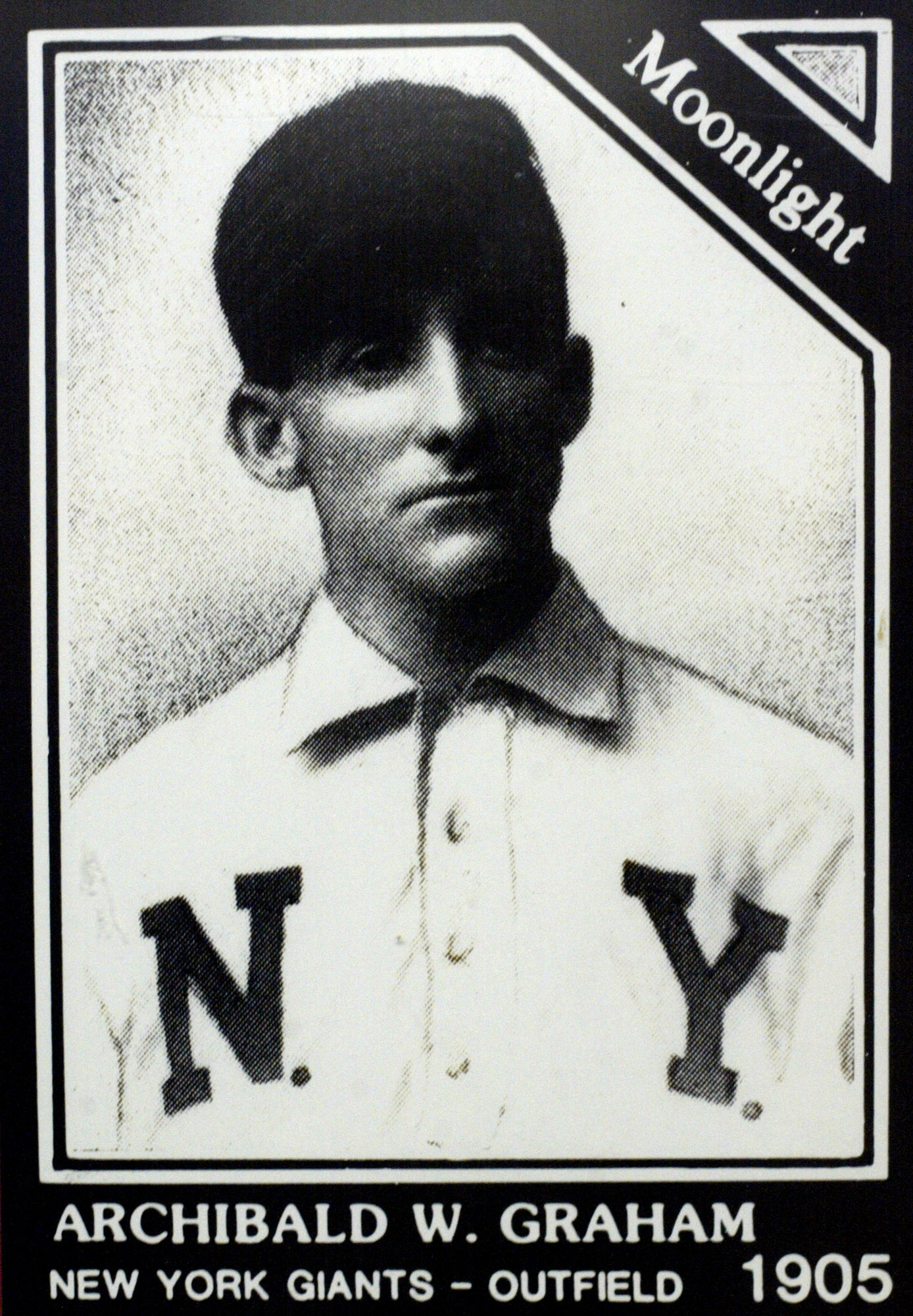

Years before writing his novel, "Shoeless Joe," which went on to become the basis for the movie "Field of Dreams," author W.P. Kinsella stumbled across an entry in "The Baseball Encyclopedia," which he received as a Christmas gift.

Graham, Archibald Wright "Moonlight"

1905, NY, N, 1G, 0 PA

“This is better than anything I could invent,’” the late Kinsella said in 2005.

Much of Moonlight Graham's historical record was accurate in the film.

Graham did play right field in the eighth inning of the Giants' June 29, 1905 win over the Brooklyn Superbas (later to become the Dodgers). The top of the ninth concluded with him on deck. He went on to work 50 years as a doctor for the Chisholm, Minnesota, school system.

What was implicit in the story of this obscure ballplayer was that he chose the right time to go. From the screenplay:

RAY: It would kill some men to get that close to their dream and never touch it. They'd consider it a tragedy.

GRAHAM: Son, if I'd only gotten to be a doctor for five minutes, now that would have been a tragedy.

After the 1905 season, Graham's character in the movie couldn't bear another year in the minors. But Graham didn't actually end his playing career in 1905. He spent three more full seasons in the minors.

There are 45 other players like Graham in MLB history: position players who played in one game without a making plate appearance. Most of them kept playing, kept chasing something beyond inclusion in "The Baseball Encyclopedia."

Through Graham, Kinsella explored how one inning could change the trajectory of a life. What if he got to the plate? What if he got a hit? Olivola said what such players are chasing is likely something more symbolic than something that might transform their and their family's well being.

Consider Deeds. He completed his degree after the 2012 season and soon took a job with a start-up company, BodyArmor SuperDrink, founded in 2011. Its business proposition was being a healthy alternative to Gatorade. Deeds was one of the first 30 employees. In November 2021, Coca-Cola purchased the company for $5.6 billion. Deeds had an equity stake. He and his wife bought their first home. They had a sense of financial security for the first time.

As crazy as it sounds, was Deeds better off not getting a brief stay in the majors?

"It's a very interesting question," Deeds said. "I really think if I got a cup of coffee, I would have tried to stick around two or three more years longer. I would have never had this opportunity with BodyArmor that put me in this situation where I am today. There's nothing wrong with being a lifer, but I probably would have been a lifer in the game.

"At the end of the day, a cup of coffee (for a month) is $40,000 to $50,000, that's what it was then. It's not going to change your life. (Going to BodyArmor) was life-altering for my wife and I. It put us back on track."

One inning in the majors might have changed Medrano's course, too.

He wasn't completely out on playing again after the 2006 season. But he vowed if Cleveland offered a coaching job, he would take it. He liked how they treated players and coaches. Cleveland called. He asked Ross Atkins, who was then director of player development, for a specific job: to be assigned to a role based in Arizona that wouldn't demand much traveling.

"I was able to see my kids grow up and be with my wife and family everyday for 13 years," Medrano said. "That's something not a lot of people get in baseball."

While many have lamented MLB's consolidation of the minor leagues - for the fewer opportunities for players and for the small cities impacted by the reduction of teams - Dodgers pitcher Walker Buehler told me in 2019 that it might benefit players who teams never plan on giving an extended major-league opportunity.

"At any affiliate, there are three players who have a chance to play in the majors. The rest of the players are there so they can play. I don’t think that’s fair," Buehler said. "You are preying on their dreams."

Deeds and Medrano felt they left at the right time. They changed course when they began thinking longer term. In a study he co-authored in 2008, Olivola found that the advice we give to other people, and to our future selves, is different than we recommend for our present selves.

"I think it's more brave to quit (than stay) in that case when it's clear there's no chance of (advancement)," Olivola said. "It's the more rational thing to do."

Smith, though, who turned 40 this year, believes one chance - one inning - would have sent his life on a better course.

"My life would be 100% different because if I would have gotten a shot, I wouldn't have blown it," he said. "I would have performed, and I would have earned a lot of money. I was good. I was really good."

Still, he says he's happy. He coaches amateur baseball players everyday.

"And softball," his daughter added from the passenger seat as he drove her to a game during our conversation.

They all let go. Every player has to. Deciding when to do it is difficult. In the coming weeks, scores of other minor-league players will have to make that same choice.

"It's not going to be the last time you have a fork in the road in your life," Deeds said. "I'm a firm believer that you get the people close to you that help you make that decision, make it, and run with it. Sometimes it's a lot easier if you ignore the rearview mirror and keep moving forward."

Travis Sawchik is theScore's senior baseball writer.