Park life: Three days with GOAT coach Tom House and his 'misfits'

Story contains coarse language

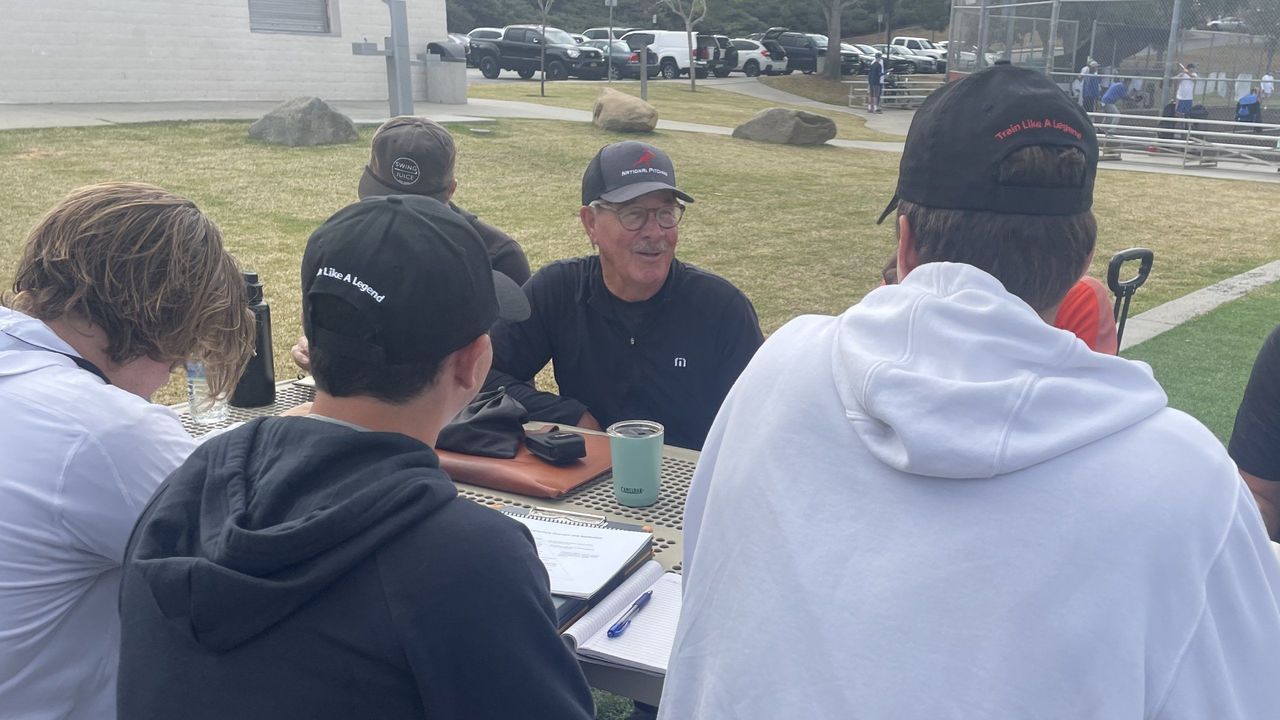

To find the Yoda of performance coaches, one must travel to a mountaintop in the far reaches of the country.

I exited Interstate 5 in early December about a half hour north of San Diego. The rental car climbed into the coastal foothills, ascending to a public space: Stagecoach Community Park in the city of Carlsbad.

What was once a stop for the two-day stagecoach journey from San Diego to Los Angeles is now a sprawling suburban space of playgrounds, tennis courts, and artificial turf athletic fields nestled between subdivisions. To unlock one's potential, no fancy state-of-the-art facility is needed. Tom House uses this space and a few other public areas near his home.

House doesn't advertise. To get here as an athlete, to attempt to master the force House teaches about the optimal ways to throw baseballs and footballs, you have to really want to be here - and House must invite you.

Those who arrive know the history.

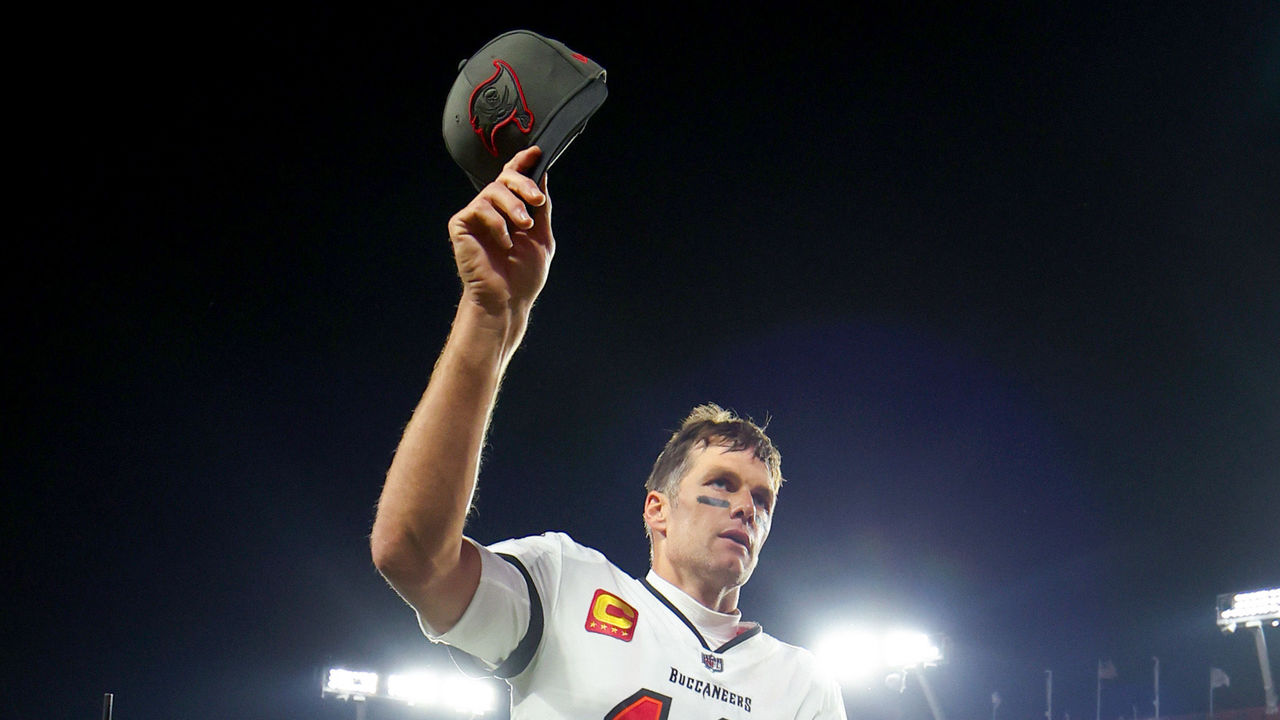

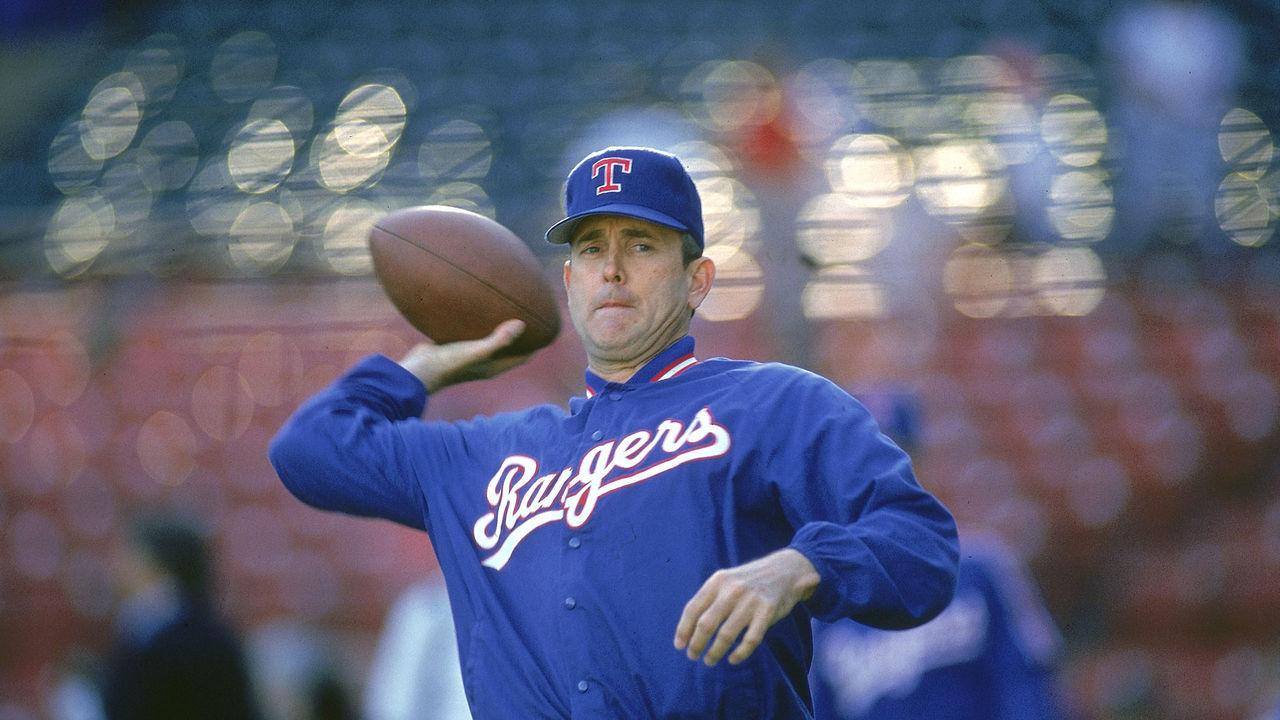

House helped resurrect Drew Brees' professional fortunes after a catastrophic shoulder injury early in his career. Tom Brady might not have played at an elite level into his mid-40s if not for House. House helped Randy Johnson after one bullpen session. When Nolan Ryan was dominant into his 40s, House was his pitching coach with the Texas Rangers.

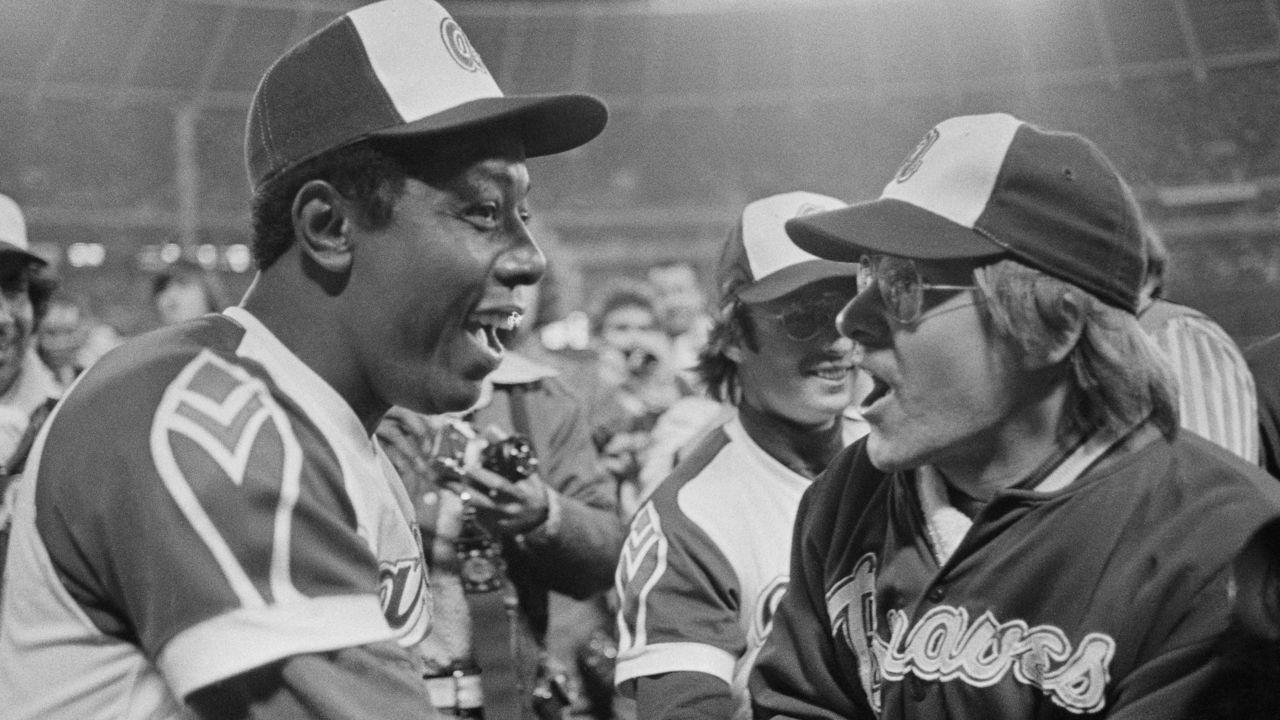

Now 75, House has been around so many great athletes and moments that he jokes he's something like film icon Forrest Gump. But his experience is real. It goes back as far as April 8, 1974. House, then a left-handed reliever for the Atlanta Braves, was watching through the chain-link, left-field fence from the bullpen at Atlanta's Fulton County Stadium. He made a prediction about where a ball might land if Dodgers starter Al Downing hung a pitch, and planted himself there. A few moments later, a ball soared through the night sky and came to rest in House's glove. He was holding Hank Aaron's 715th home run.

House calls himself lucky often, even though he's been battling Parkinson's disease for years.

House built his coaching reputation as a pioneer in the field of biomechanical analysis and weighted-ball training. The so-called "father of modern pitching mechanics" also holds a Ph.D. in psychology. He's accumulated as much wisdom as perhaps any coach on the planet.

He says he was "put on this earth to be a coach," and his passion for the craft is apparent on this December day. He's seated at the center of a picnic table between two recreational baseball fields, surrounded by three-minor league pitchers, a couple of pro hopefuls, and a quarterback from IMG Academy.

They wear hoodies, generally from their pro or college team's apparel stock. One of the hopefuls here, Jack Liebesman, sports a Brady T-shirt bearing a screenprint of a cartoon goat.

I once caught a home run in the bullpen then ran it in to give the ball to Hank Aaron.

— Tom House 〽️ (@tomhouse) January 28, 2023

House calls them a family. The athletes call themselves "misfits." They don't rank with Ryan or Brees but they're here to try to find new levels of performance in themselves just the same.

House is also able to help thousands of athletes from a distance through the Mustard app, launched in 2020 to democratize his wisdom and data collection. The app employs a smartphone's camera to capture an athlete's movement and compares it to optimal patterns from the app's database. His knowledge is also shared in books he's written and research he's published, too. But there's something about hearing his sage advice in person.

"There is some magic from Tom that can never be bottled up when he is working with somebody," says Mustard CEO Rocky Collis. "Not just the speed in which he can identify an issue but also the one sentence that can come out of his mouth that will fix that thing."

Collis says House often recites a definition for wisdom: "Knowledge plus experience."

Collis marvels at House's contributions to sports and the elite list of players he's helped. Successfully working with both Nolan Ryan and Brady on their performance mechanics is quite an achievement. "'Why is one guy responsible for both of those things?' is a really interesting story."

Monday

House works with smaller groups, six to eight athletes, his ideal teacher-to-student ratio.

His program is taught officially through the National Pitching Association, the organization he co-founded to teach functional strength and mechanical efficiency, but this offseason group is unofficial.

They meet Monday through Friday in public spaces like this one, and each morning House opens with a lecture, a graduate-level course in throwing an object.

They listen for 20 minutes, are free to ask questions, and if you appear to be drifting off, House is likely to toss a question your way to keep your head in the game. He wants them to understand the hows and whys of what he's asking them to do.

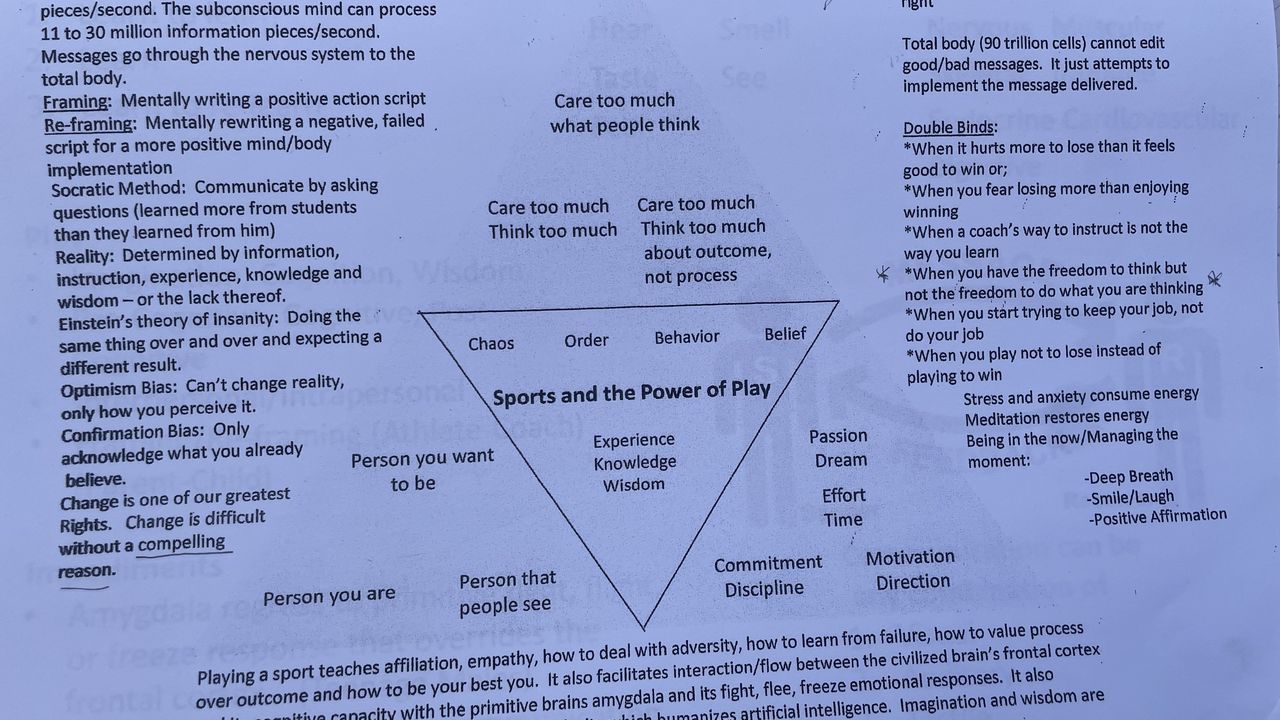

They each have a spiral-bound booklet containing some of House's wisdom. They also have a notebook and a pen.

"Pull out the kinematic sequence," he commands. His ball cap and tortoise-shell glasses make him look like both coach and professor. The mustache he's worn since his playing days has grayed.

On the page they're looking at is a chart - a series of lines that jump and spike, appearing something like an ECG reading.

"OK, that graph right there is of who?" House asks.

Silence.

"That's Greg Maddux, OK, and he's got perfect timing sequencing."

There is an optimum sequence through which various parts of the body need to accelerate and decelerate when throwing an object, or swinging a bat or golf club. House helps golfers, too. Maddux is one of the all-time greats in the efficiency of his pitching movement. House was able to capture his delivery with his nascent motion-capturing system.

House talks to the group about the foot-strike. He's found the best throwers move fast down the mound. There's an acronym he often recites, "GFF": Go forward fast.

So fun catching up with Nolan Ryan recently. I asked him, “What pieces of advice would you pass on to pitchers?”

— Tom House 〽️ (@tomhouse) May 5, 2022

His answer:

1) Always be in a hurry to the plate

2) The more tired I got, the faster I’d try to move to the plate

3) Grunt in front

He moves to discussing the various lines that spike on the chart representing the acceleration and deceleration of movement of the hips, shoulders, elbow, and hand.

"You see where the peak goes? Where it stops?" House says, scanning the faces around the table. "See what the hips do? The hips go first. And then the hips stop, and then the shoulders."

Joey Steele, a minor-league pitcher with the Miami Marlins, asks a question. He wonders which lines on the graph represent angular velocity and which are linear. Angular velocity is the speed at which something rotates around an axis, linear velocity is about speed of movement in a straight line.

"Everything in that little sequence is angular movement. This is the only linear," House says, pointing toward the chart.

Steele follows up: "Was his hand the only thing going linear?"

More questions follow.

"I can't believe you guys are having trouble with this," House says, slightly exasperated.

Some look sheepishly down at their notebooks. These are not subjects that are commonly discussed in baseball. But just as the "Moneyball" revolution ushered in a way of using spreadsheets of game data to find hidden advantages in player valuation, the new data age is centered around understanding physics to raise performance.

House asks another question, and Steele answers it before House can finish saying "mass times acceleration."

"Right. Now you're getting it," House says. "So, cotangent. What does that mean? You're edumacated."

House doesn't need his students to necessarily master trigonometry, but he wants them to understand the concept of stored energy, and how to release it efficiently.

Torque, expressed as the twisting of shoulders, is responsible for about 80% of pitching velocity, according to House. The back shoulder shouldn't begin to turn toward the target until the front foot hits the ground.

With younger athletes, to explain the concept, House likens the creation of torque to those model airplanes where you turn the propeller to twist the rubber band and store energy.

A couple of his students here are trying to increase their velocity. One is Levi Wilson, a 6-foot-3, 200-pound right-handed pitcher from Georgia, whose shaggy blond hair gives him the look of a SoCal native. He wants to sign a pro contract. Before House will summon the scouts, Wilson must hit 95 mph.

Joao Arede, a quarterback by way of Brazil, also needs more zip on his throws. He looks the part: 6-foot-4, 210; lanky and lean. His goal is to throw a football 50 mph this week. The NFL Combine average is 54 mph. He's coming back from a shoulder injury and hopes to walk on at UCLA.

In the coming days, they will test.

House doesn't have to be here but he still loves to coach; it's a reason to push through the tremors in his hand, the stiffness. Parkinson's has robbed him of much of his mobility and endurance. He can't stand for long periods during workouts, but he's lost none of his wit, wisdom, or eye for seeing things.

And just as others helped him, he wants to pass down what he's learned, starting with his earliest lessons in college ball.

When House arrived to throw one of his first bullpens with the University of Southern California baseball team, Tom Seaver was tossing laser beams alongside him. This was a time before handheld radar guns. House probably threw in the low 80s. Seaver? Much faster.

"Coach came up and put his hand on my shoulder. 'What do you think of young Tom Seaver?'" House recalls of his conversation with college coaching legend Rod Dedeaux, who won 11 NCAA titles in his 45-year career.

Seaver would go on to be selected in the first round of the 1966 draft and had a Hall of Fame career.

"Coach, if you need me to do that, you have the wrong lefty," House said.

"No, I don't need you to do that. I need you to do what young Tom House does best," and that was featuring his bending curveball, Dedeaux said.

House was drafted in the third round in 1967.

A few years later, House, then 23, was struggling and was sent to repeat a year at Triple-A for the Richmond Braves. It was spring 1970 and manager Clyde King asked him to walk with him one afternoon to the bullpen at Parker Field.

As they strolled, King asked, "What is your ERA the first time through the lineup?"

House had no idea.

"It's a little more than two. It's not bad," House recalls King saying.

"I'm thinking, 'Hmmm. Maybe I got a chance,'" House says.

King then asked, "What's your ERA the second time through?"

Again, House had no idea.

"It's sneaking up on six," King said.

"I'm thinking, 'Fuck, I'm in trouble,'" House says.

"He said, 'What is your ERA the third time through?'"

House knew this one. He'd never made it through the third time.

King had an accounting background, so he was used to dealing with numbers and risk.

"This was before Bill James," House says. House was receiving a lesson in platoon splits before James ever wrote about them.

"He said, 'I'm going to move you to the bullpen because I don't think you're ever going to start at the major-league level with your durability,'" House recalls.

"That's the only reason I got to the big leagues."

House went on to have an eight-year major-league career, compiling a 3.79 ERA and 103 ERA+.

"See how I got people to help me out with what I could do? Not trying to make me something I couldn't be?" House says. "See how lucky I got?"

For a few hours, his group goes about their individual drills. They throw normal baseballs and footballs. But they also toss weighted balls, attach large elastic bands to chain-link fences and stretch. These once unusual practices have become common in baseball. Sometimes they whip towels instead of baseballs or footballs. The towel drill, and some other NPA practices, have their critics, but it's hard to argue with the client list.

House asks an assistant what time it is. He needs a ride home so he can be seated in front of his television by 5 p.m. Pacific time. Brady, his most famous client, is playing tonight. He must watch in real time.

House says it's possible Brady will call at halftime and ask, "What do you think?"

Tuesday

They reconvene at the same picnic table late Tuesday morning, and the subject turns to building strength.

"How many muscle groups accelerate" in the arm, House asks.

"Three," says Liebesman, one of his better students. "And you have two to decelerate."

"You can only accelerate what you can decelerate," House adds.

To obtain elite arm speed, one requires the accelerating muscles to properly move the arm briskly, then the decelerators to put on the brakes. The body, House said, won't allow the arm to move faster than it can slow itself.

House adds that gravity, while moving down the mound, also increases force and the need for strong brakes.

In softball, because there's no mound and because pitchers throw underhand, there's far less stress on the decelerator muscles.

House always wanted to learn whys and hows of the body's mechanics. Perhaps that's because his father, who he described as the "ultimate nerd," was a civil engineer and a natural problem-solver. Perhaps it's because his mother stressed academics over sport, steadfast in her "No A, no play" rule.

For a half century, he's been trying to answer questions.

House and John "Coop" DeRenne grew up playing amateur baseball together. DeRenne played two years in the Montreal Expos system before becoming a kinesiology professor at the University of Hawaii. DeRenne's House's "research buddy," he says.

In the late 1970s, DeRenne found an article about the unusual training methods employed by Ukrainian Olympic gold medal hammer thrower Anatoliy Bondarchuk. Bondarchuk employed practices like using lighter training implements to build speed and heavier ones to build strength. Bondarchuk became a coach and wrote about training techniques for every major field event that involved throwing or rotational movements. They were fascinated by his concepts.

"We stole everything from Bondarchuk," House says. "Coop and I figured if it works for javelins, it should work for weighted balls."

While some pitchers had trained with weighted balls, like fellow pioneer Mike Marshall, no one had done any scientific testing. House rounded up some college and high school pitchers to be used as guinea pigs in their first studies in the early 1980s. He co-authored the work with DeRenne.

"(DeRenne) and I did the first velocity study with the six-, five-, and four-ounce balls," House says. "That was the initial study. ... That was the beginning of what you see right now."

The research expanded, with further work being done by the American Sports Medicine Institute and Driveline Baseball. Weighted balls are now a common tool in pro ball, and the training regimens are playing a role in velocity gains.

In the 1980s, House believes it was rare for a pitcher to average 90 mph. In 2007, the first year of official pitch-tracking data, the average fastball in the majors was 91.1 mph. Last year, it was 93.9 mph.

"Like with Jim Ryun and the four-minute mile," House says, "once people saw that you could throw 92, 93, it just kind of pulled the system forward to where, 'Yes, it is possible.'"

What are the limits?

"I have had seven or eight kids throw a two-ounce ball 118 mph. We know the arm can go that fast," House said. "But can it go that fast with a five-ounce ball and remain durable and still throw strikes? I think, eventually, we'll adapt to something along those lines."

After Tuesday's opening lecture, the players begin their individual work.

House motions toward one pitcher.

"That's my Eckersley," he says of Cam Brown.

Like Dennis Eckersley, Brown throws sidearm with unusual extension. Brown essentially leaps from the pitching rubber. House worked with Brown for more than a year on honing his delivery.

Brown explains that teams like "the leap, the plantar flexion," reciting House terminology. "For my height, my extension is way out there. … It gets me closer to the plate and moving faster," Brown says.

Brown being in professional baseball is a minor miracle.

Looking to add velocity off the mound during his senior year at Central Michigan to entertain the pipe dream of being drafted, Brown procured a contact number for House through a college teammate's father.

Initially, there weren't the results he wanted. He went undrafted and failed to impress scouts in his first workout. But after a few months of working on and off with House and a month with the independent Windy City Thunderbolts, House arranged another workout. Twelve teams called. Brown signed with the Detroit Tigers.

He pitched 32 2/3 innings for the Tigers' Class A affiliate last year. He struck out 31 and allowed only 25 hits, posting a 0.55 ERA, which earned him a promotion to High-A.

"(House) knows how you need to learn," Brown says. "He can read people. He loves watching us get better. I don't think he's going to stop until he physically can't do it."

In early August 1992, the Rangers were in Seattle. The Mariners had a struggling giant on their staff: the lanky, 6-foot-10, 28-year-old Randy Johnson. Nolan Ryan was Johnson's idol, and like House, Johnson was a USC product.

Hours before a game in the series, they met Johnson at the Kingdome. The two uniformed Rangers personnel visited with Johnson in the Mariners bullpen, in foul territory on the playing field down the first-base line.

Johnson made a few throws. House made a suggestion. Instead of landing on the heel of his right foot in his delivery, he ought to land on the ball of his foot.

In 125 1/3 innings that season, Johnson posted a 4.52 ERA and walked 97.

After the bullpen session, Johnson posted a 2.65 ERA over 85 innings and struck out 117 while cutting his walks to 47 - a reduction of about two walks per nine innings.

In a one-on-one discussion with Ryan for a magazine piece in 1996, Johnson said: "It's unheard of, unfortunately, to have other people on another team take the time to help another professional athlete. … You and Tom House didn't have to help me."

Much of House's eye comes from studying video, motion analysis, and staring at biomechanical stick figures for 40 years. He's almost apologetic for his ability to "see things," drawing from his mental library.

House was hired by the Rangers in 1985 when the club was looking for an edge to close the gap with rivals who had more resources and talent.

House credits then GM Tom Grieve and manager Bobby Valentine's openness for allowing his experiments. "They were behind it 100%," House says.

Even future U.S. President George W. Bush, the managing general partner of the team's ownership group, gave his approval.

"I got along with Barbara the best," House said of the Bush family.

The experiments included one of the first biomechanical labs in North American pro sports.

He arrived in Texas fascinated with the process of another Olympic athlete, Gideon Ariel, who competed in the shot put and discus and was one of the first athletes to use motion-capture analysis to improve his throwing mechanics.

House took out a second mortgage on his home to buy Ariel's motion-capturing system. His first wife wasn't pleased with the investment nor the year-round coaching obsession. After the end of one of his first seasons with the Rangers, he returned home to find the locks changed.

He was further stressed trying to make sense of the moving stick figures generated by the system.

"We were sitting there with the system in spring training, and Bobby (Valentine) said, 'How are we doing?'" House recalls. "I said we got some great captures. He said, 'What are we doing with it?' I said, 'I don't fucking know.'

"But all of a sudden, boom: Guys that are really good do this, everybody else does this. The modeling got better and so did the questions."

He often brought the system on the road when the Rangers traveled, too, placing a camera behind home plate, and on the third- and first-base sides before games. Did anyone ever bother him before a game?

"Nobody gave a shit because no one knew what motion analysis was," House says. "Did you see how lucky I got?"

He collected four seasons' worth of data on a number of major-league pitchers.

He brought other things to Texas, too, like weight training, monitoring players' sleep and nutrition, and training with heavier implements. That included the then unusual - but now common - practice of pitchers throwing footballs in the outfield before games.

House has found it easier to get buy-in from the best performers.

"It turned out to be the opposite of what you would think," House said. "When not just Nolan, but all these elite, elite, Hall of Fame, the GOAT guys - if it makes sense to them, they are on anything new that will make them better."

House got the football idea from Dick Dent, a trainer with the Padres, when House was a roving minor-league instructor with San Diego in the early 1980s.

"(Dent) found they worked harder and had more fun in recovery, and their arms were recovering faster," House says of that between-outings work. "He noted the guys who had the best spirals also had the best arms."

In one of House's last games as Texas pitching coach, he watched Johnson strike out 18 Rangers - just weeks after helping him. Valentine got the axe at midseason and House was fired after the season. It was his last as a major-league pitching coach.

"I don't know if it hurt me, but it certainly didn't help that we'd been working with someone in our division," House said

The Oklahoman reported at the time: "some baseball insiders say (Texas) has gone from the worst pitching coach in the game, Tom House of Texas, to baseball's best, Dave Duncan. … House's coaching methods have been called revolutionary by some, revolting by others."

One of House's few laments is about those early years.

"If I had to do it all over again, I wouldn't have been confrontational at the beginning," he says. "I knew our stuff was good."

At some point during Tuesday's lecture, House asks everyone, even "our visiting dignitary" as he labels me, to place our hands on the picnic table, palms down, digits extended. He wants to examine our fingernails.

Our fingernails?

If you have any white specks on your nails, he explains, it's a sign that something is wrong with your blood chemistry. His nails are pristine, and so are most of the others at the table. I have some white specks. House says he's seen sportswriters in worse shape, but that I might want to make some dietary changes.

In part to cope with Parkinson's and forestall its progress, House attempts to keep himself in as flawless shape as possible. He's defied the odds and believes athletes can alter their aging curves, too.

In 2012, he told a Boston Herald reporter that Brady could play until he's 45. At the time, it seemed like a crazy prediction.

A year earlier, House made a trip to Foxboro, Massachusetts, to work with Brady. At the practice facility one day, Bill Belichick called them into his office.

"'Tom House, tell me why I should keep Tom Brady?'" House recalls Belichick's questions. "'When all the history of QBs in the NFL tells me they usually peak about age 32-34, why should I keep and not trade him right now?'"

Brady was in his age-34 season. Belichick is emotionally detached in his decision-making and unafraid to move on from a player despite his status with the team or the fans. When Belichick began his head coaching career in Cleveland in the early 1990s, he released popular quarterback Bernie Kosar during his age-30 season in 1993, citing "diminishing skills," although the QB was also feuding with Belichick over play-calling. Belichick won his first NFL playoff game the next season with Vinny Testaverde, who is 12 days older than Kosar, at QB.

"'Well, I do know this, Bill,'" House said. "'If the athlete is willing to pay the price, like Nolan Ryan did, there's no reason he cannot be just as good at 45 as age 25.'"

In his first season working with House, Ryan, at 42, had his second-best season by WAR (7.0) and strikeout percentage (30.4%). Ryan's age-41 to -45 seasons are the most productive in MLB history for a 40-something pitcher.

Here’s a great video with Nolan Ryan, @RockyCollis and myself. We talk about tucking the elbow to stay on line during your throw.https://t.co/uAshDOovZ8

— Tom House 〽️ (@tomhouse) November 18, 2022

Years later, a significant portion of Ryan's Hall of Fame induction speech was directed toward House.

I was very fortunate to have a pitching coach by the name of Tom House. … Tom is a coach that is always on the cutting edge and I really enjoyed our association together. … And because of our friendship and Tom pushing me, I think that I got into the best shape of my life during the years that I was with the Rangers. And Tom, I really miss those days that we spent in the weight room and out on the field working together. And that last year that you weren't there, I can really say, buddy, that I missed you.

As House recalls that Belichick visit, he says: "I'm not going to say that's the reason the Patriots hung on to Tom as long as they did, but I know it's a part of their explanation."

Arede, the quarterback in the group, became interested in American football in Brazil through fantasy football. Although his velocity is lagging, he puts very good spin on the ball.

House says the best QBs have a lot of spin, and efficient gyroscopic spin like that of a bullet. The less wobble the better.

"Brady has always had spin rate," House says. Brees too.

"Play catch with Drew, you can hear it spin," House says, mimicking the sound of a football cutting through air. "Shhhhhhhhh. You can hear it coming.

"With no spin rate, it's like catching a brick. Blake Bortles … he threw a football and it just knuckled. Same with (Tim) Tebow. Tebow could not spin a ball."

Arede can spin a ball. What he needs is velocity.

House says he's found ways to teach spin rate in baseball, but not football. What he can do is teach velocity.

House didn't intend to work with quarterbacks. He got lucky, he says.

In the early 2000s, House was giving baseball instruction to a son of Cam Cameron, the San Diego Chargers coach. Cameron asked House if he'd ever consider working with a quarterback. He knew one he thought House could help: Brees.

Initially, Cameron wanted House to work on Brees' huddle presence and mental game. As a shorter quarterback, he worked with Brees getting lower in the huddle, often in a catcher-like squat, to force his teammates to lean in and get nearer to eye level.

After Brees' injury, Dr. James Andrews rebuilt his shoulder, and House rebuilt Brees' mechanics. House found there was tremendous carry-over to pitching.

"I was literally with Drew every day for four months," House said. "He's like one of my kids."

Given Brees' success, other NFL and college QBs began calling.

It led to 3DQB, a quarterback development coaching group co-founded by House, which works with more than 20 pro QBs today, including Philadelphia Eagles QB Jalen Hurts. 3DQB's webpage sounds a lot like modern baseball: "Every delivery must be properly timed and kinematically sequenced."

During a ManningCast last year, Eli Manning commented on Dak Prescott's warmup routine being shown on air: “That’s the Tom House stuff!"

Accuracy and velocity were thought to be difficult to improve in NFL circles. House is always challenging conventional wisdom.

Arede wants to test today. They move beyond the baseball fields to the multi-purpose artificial turf, crisscrossed with lacrosse and soccer boundary lines. The pitchers run routes as Arede warms up. There's also a new face today, former Wake Forest wide receiver Donald Stewart, who's hoping to sign with an NFL team.

Stewart met House when he was training at a nearby high school where House was working with some pitchers.

House noticed Stewart caught the ball better on one side of his body and suspected it was because one eye was weaker than the other. He suggested wearing an eye patch covering his stronger eye for a few hours a day to strengthen it. Stewart tried it and said it helped. House's magic isn't limited to stationary throwers.

Before his test, Arede throws with a one-pound baseball of sorts, an equivalent weight to a football. He hits 53 mph. That's encouraging to House, a good number. If he can throw a one-pound sphere 53 mph, he's physically capable of throwing a football 53, about the NFL Combine average.

Deshaun Watson's draft stock declined in 2017 because his top throw at the combine was 45 mph. Josh Allen set a combine record with a 62-mph throw. After years working with House, Brady shared a gun reading of 61 mph with his followers.

Arede takes a half step and unleashes a throw to begin the test.

"Forty-four," is called out as the radar reading.

I'm standing with House some 20 yards away.

"Justin, come here really quick. Explain what thresholds are," House said.

Justin Courtney is another of his better students.

Courtney was an undrafted pitcher out of the University of Maine in the spring of 2020, coming back from Tommy John surgery. He threw 88 mph in his backyard when he began working with House.

A New England sports fan, he sought out House after he watched the "Tom vs. Time" documentary. He was fascinated watching House coach Brady on concepts like not having his elbow extend too far away from his body, and avoid having his head jerk and throw off balance.

"Just keep all your shit inside critical mass," House said to Brady in 2017.

It's similar to the advice he's giving in a community park more than five years later - the importance of keeping the head aligned, and over the athlete's center of gravity, as the head accounts for about 8% of body weight.

After watching the doc, Courtney sent House an email. Miraculously, House got back to him and was willing to work with him. House liked that Courtney was 6-foot-4, 220 and that he was curious.

After months of remote work during the peak of the pandemic, Zoom calls, and work with the Mustard app, he hit 98 mph. House set up a workout. Courtney bought a one-way ticket to San Diego. He planned either to get signed or work with House. He wasn't coming back.

Last season, the 26-year-old was promoted to Double-A with the Mets, where he struck out 10 in 7 2/3 innings.

Courtney can explain thresholds.

"So you have physical thresholds and mental and emotional thresholds. (Arede) tricked his body into 53 (mph) with a one-pound ball, but as soon as he put a football in his hand … he reverted back."

"Why?" House asks.

"Your body kinda has a governor on what it thinks is safe," Courtney explains, "and you kinda have to take the governor off in order to reach the next threshold."

House seems pleased.

Says House: "The 53 is encouraging. I didn't think I'd see that today."

Arede makes his way over and tries to assess his performance, and the rest of the group follows along. A huddle forms.

"I felt more pain with the football than the one-pounder," Arede says.

House wasn't worried about the pain, suggesting it was more mental than real: "When you threw with X amount of velocity and got hurt, that little village in your shoulder is saying: 'Fuck this, I ain't gonna do it.' So how do we overcome the thresholds, Joey?"

"Stop thinking," Steele said.

"For you, that works every time," House says. "But there's a physical way to do it."

"Train with something other than the implement in your hand," Steele says. "His brain needs to figure out and trust that he can go faster than he actually can."

House seems pleased again.

"What did we do with you (Courtney)?" House asks. "We took away the five-ounce, made you do what?

"Four-ounce only for a couple months last offseason," Courtney says.

"Do you think he needs to do a heavier football or lighter?" House asks.

The group pauses.

Says House: "If we know his functional strength is what it should be, but when he throws he cannot get through the threshold, are we going to work on more strength or more speed?

Wilson: "Speed."

"Yeah," House says, "because I think he is strong enough."

House turns to Arede.

"I know you hate that little pee-wee football," he says of the underload training tool, but he's recommending it again.

He pivots back to the group as a whole.

House turns to Wilson: "When do you want to test?

Wilson says he's ready.

"Rest of you guys get on with your drills," House says. "Go boys. Giddy up."

Later that day, Courtney talked about working with House: "Confidence. That's what he gave me. I was on the outside looking in. No connections to get into professional baseball, and then he's out here telling me I can be a big leaguer through Zoom. Why has no one ever told me that?

"He's the best performance coach in the world."

Wilson begins throwing from his knees. It's part of a progression. A study by the NPA found pitchers can reach 78% of their velocity by throwing from their knees. That means a 75-mph toss from one's knees ought to equal 95 mph on the mound. That means a significant amount of velocity comes from the rotational movement.

From his knees, Wilson attempts to create as much torque as possible. He unleashes a throw into padding attached to a fence and grunts.

"That means he's shitting nails to throw," House says, about 15 yards away. "I'm going to guess his next fastball is going to be 74."

Courtney holds up his phone with a radar app open and trains it on Wilson.

"Seventy-six," Courtney hollers back to House.

"That should get to 95 on the nose," House says.

But when Wilson rises to throw in a full delivery, the big test, his first offering falls short of 90.

"Did anyone bring their four-ounces with them," House says of the lighter baseball designed to increase arm speed.

Someone has.

Wilson makes a few tosses with the four-ounce balls. Then back to his challenge of throwing 95.

"Eighty-nine," Courtney says.

Wilson throws another at max effort: 89.

"One more," House says.

"C'mon Levi!" someone exclaims, the misfits pulling for each other.

House turns to me: "It's in there."

Wilson breathes in, exhales, and uncorks another high-effort offering.

Eighty-eight.

"OK, enough," says House.

Wednesday

Wednesday's lectures are focused on mental and emotional aspects of performance. These are critically important, House says. The timing's ideal as the group reconvenes a day after failed tests.

The focus is on Levi as they sit at the picnic table.

"All his numbers, everything he did, showed he should be able to throw 95," House said. "But he's got the creature."

The creature is another term for the yips, the terrible mental block that can derail performance.

"His creature is different than guys who can't throw strikes," House said. "His creature is a double-blind between his conscious and subconscious. His conscious mind wants to play pro ball so fucking bad. He can taste it. His subconscious mind says 'No.' It says, 'We're not going to put you in a situation where you can fail.'"

"That makes sense," Wilson says.

"Of course it fucking makes sense," House says. "That's where you are, but think about how far you've come. A year ago, I don't even remember how you threw.

"You think the world is passing you by but it hasn't. You're still a puppy."

House wants him to face hitters "ASAP" to get over the issue. The easiest way to do it is to keep training with House, and join something of a high-level adult baseball league in nearby Palm Springs, which wouldn't affect his college eligibility should he need it. There, he'd get 40-50 innings against college, between-college, and some pro hitters.

Wilson seems hesitant about the idea.

"That's what I think you want to do. But I'm not you," House said. "I'm 75 and I've fucked up more things than you'll ever think you can fuck up. I have this thing called wisdom. If you were my son, or if I was you and I knew what I know now, I would be over in Palm Springs the first day of their spring. So just let it fester."

It's quiet for a moment. Courtney asks Wilson from across the table: "How old are you, Levi?"

Twenty, he says.

"He's a fucking puppy," House says.

"Yeah, you don't want to go straight from here to an organization," Courtney says. "They will put all the college guys ahead, and you'll be stuck in rookie ball for a year and half."

House, suggesting patience, cites an example at the end of the table. "Cam, tell them what Mike Elias with the Orioles told Rocky about you?"

Brown had failed in a workout, and logged innings in an independent league - then it clicked. He got his contract.

Collis had brought up Brown's name in conversation at the Grand Hyatt hotel at the winter meetings a night earlier when Collis and House made the rounds and met with a team.

"(Elias) said, ''I know who you are talking about,'" Brown recounts.

"How did Mike Elias know about him when Detroit tried to bury him in rookie ball?" House asks. "They didn't want anyone to see him all summer long, why?"

"Because he's fucking good," Courtney says. "This is the GM of the Baltimore Orioles."

House wants Courtney to share another story, about Courtney running into the Mets' farm director a night earlier at the Grand Hyatt. Courtney was told to get ready to face big-league hitters in Florida.

"(Courtney) was in his backyard, in bum-fuck Maine two and half summers ago," House says.

Not that there's anything wrong with training in a backyard.

"Did I tell you what would happen?" House asks rhetorically. "Was I wrong?"

"Never," Courtney says.

House turns back to Wilson.

"If you were 31 with a wife, two kids, and a mortgage, I'd tell you to go home," House said. "The tools are all there. Your subconscious and conscious brain won't let you show them off. That's what you have to get over."

They go through their work. A few hours later, the day winds down. The group scatters until tomorrow when the process continues.

It's not complete hyperbole when House calls himself the Forrest Gump of sports considering who he's coached.

He calls himself lucky repeatedly even though his fight with Parkinson's can't be won.

"I was just fortunate that the beginning of my playing career, and coaching career, was right at the start" of the age when tech met training, he says. "I got lucky. I was in the right place at the right time."

He also positioned himself in the right places and was capable of meeting the challenges of the new age.

He knew where to stand when Henry Aaron came to bat on a spring night in Atlanta in 1974. Even though his career began before radar guns, he knew there was something to motion-capture analysis and high-speed video. He was willing to experiment, to fail, to learn, and be different.

His legacy is secure as a pioneer and as one of the great performance coaches of our time.

Perhaps his last great quest is to democratize what he's learned through the Mustard app. He laments that millions of kids quit playing baseball and other sports before they're 14. He wants them to play longer. He knows only a few can go pro, but the life lessons from being a teammate, competing, and staying in shape that come with sport are invaluable. He still wants to make an impact and share.

The app means much of his wisdom can live on for years. But there's nothing quite like working with House the coach, learning the mysterious ways from the Yoda of throwers. He says this is what he was born to do.

"He'll say once in a while: 'I'm not going to be around forever,'" Brown says. "He'll say: 'When I die, this stuff dies with me or you guys will carry it on.' Which is a heavy responsibility. But at the same time, it's really cool we have access to that everyday. He's the best in the world."

Travis Sawchik is theScore's senior baseball writer

HEADLINES

- MLBPA deputy director shaken by events that led to Clark's resignation

- Santander explains injury: Torn labrum didn't show on MRI in 2025

- MLBPA head Tony Clark resigns after reported inappropriate relationship

- Stanton feels Yankees career will be 'incomplete' without World Series win

- Padres sign longtime rival Buehler to minor-league deal