Are the Blue Jays creating a launch pad with their new fences?

This winter's renovations to Rogers Centre in Toronto are focused on improving the fan experience, creating new revenue streams, and updating the players' facilities. But the ballpark makeover will have another significant impact, intended or not: it will change the offensive environment.

To accommodate some of the alterations, the playing surface is going to shrink.

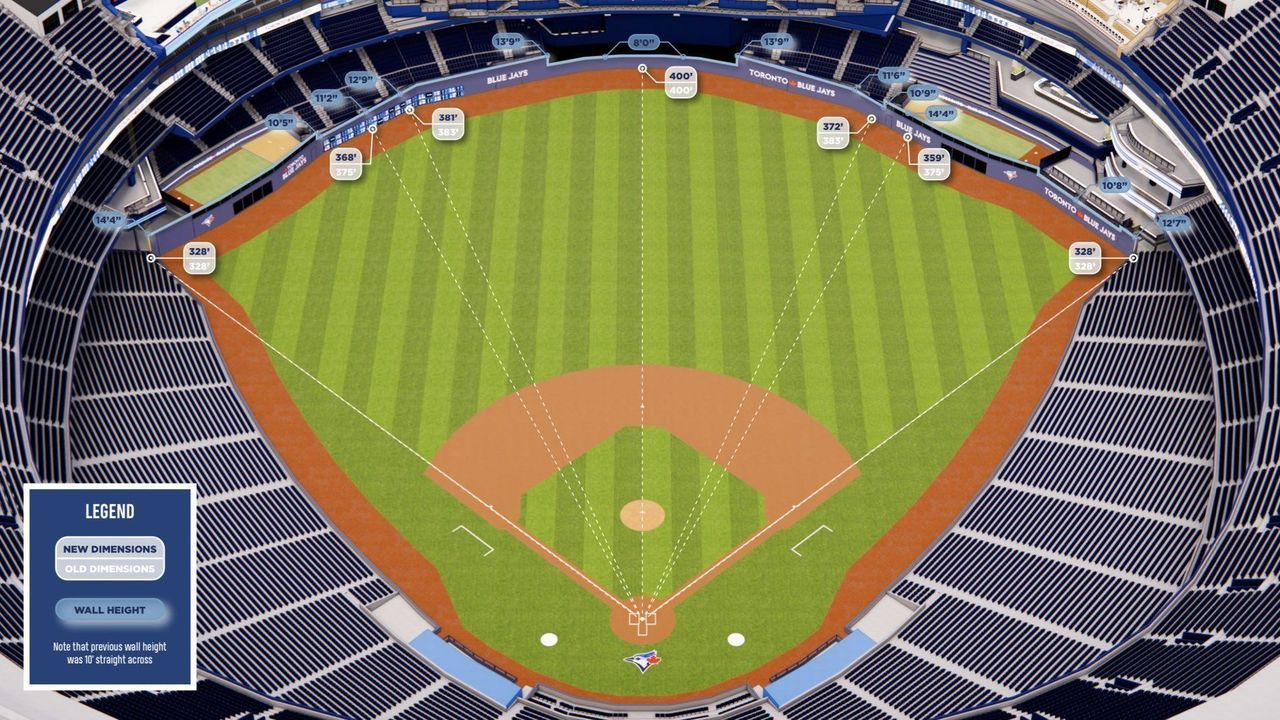

The fences are moving in throughout much of the outfield, which will no longer be symmetrical. And while fence height is also increasing in some areas, it seems unlikely to be enough to keep the park home-run neutral.

The Blue Jays say their modeling predicts the venue will play like it did with its previous dimensions - outfield dimensions unchanged from its opening in 1989 when the facility debuted as the state-of-the-art SkyDome.

Along with Dodger Stadium, Wrigley Field, and Fenway Park, it was the only MLB stadium to not change its outfield dimensions in those 34 years. Many clubs have brought fences closer - except Baltimore - or opened a new stadium in that period. Many teams have opened new ballparks and changed dimensions.

"Our team modeled these adjustments, and we anticipate they will create a similar, neutral environment," Marnie Starkman, the Blue Jays' executive vice president of business operations, told reporters last month.

To investigate the claim, theScore consulted with baseball physics expert Dr. Alan Nathan to explain what the changes might mean. We also reviewed every Rogers Centre fly ball from last season that we felt could be affected by the changes.

We used Statcast's distance projections and launch angles and also employed the eye test to try and discern whether a ball would or would not clear the new fences. It's by no means a perfect study, but hopefully it gives us a general idea of how the park will play.

What we found: The Blue Jays are going to need a bigger wall if they want to keep home runs neutral. The Rogers Centre could become the most favorable place in the game for long balls.

First, let's first review the changes.

The most consequential move is in right field. Straightaway right field, where the visitors' bullpen sits, will be moved in 16 feet from 375 feet. At 359 feet, it will be one of the shallowest right fields in the majors. For reference: Yankee Stadium's right field is 360 feet from home plate.

The average warning track depth in the majors is 15 feet, so the new right-center wall will essentially rest where the old warning track began. Warning-track power now becomes game-changing power up north.

Moving toward center field, in what the club refers to as the right-center power alley, the fences will move in 11 feet to 372.

The distances down the lines will remain at 328 feet, although the wall heights will be raised in both corners.

In left field, the walls are also coming in - though not as significantly.

The new distances from home plate will also create new angles along the walls themselves. The first 70 feet of left-field wall from the foul line across the front of the home bullpen will be slightly shallower than its previous iteration. The wall then recedes to the left-center area, with another new angle created.

To try and neutralize the effects on home runs, the Blue Jays are also raising the fence height in a number of areas, most dramatically down the left-field line, in right field, and in deep left-center and right-center field. Wall heights will be raised there as high 14 feet and 4 inches, up from the previous 10 feet, which was uniform around the entire outfield.

Dead center remains 400 feet from home plate, though the center-field wall height is decreasing from 10 feet to 8 feet.

It's tough to know from the artist's rendering whether the Teoscar Hernandez drive below, which didn't quite make it over the 10-foot wall, would have cleared the new 8-foot wall or hit the adjacent 14-foot section.

When it comes to trying to offset closer outfield distances with higher walls, Nathan said there is a close relationship. Bringing in the wall distance by a foot will play the same as raising the wall height by a foot.

And the Blue Jays are generally cutting distances more than they're raising heights. Nathan says the angle of decline of a fly ball is steeper than its incline.

"The ball actually covers more horizontal distance on the way up than the way down because the forward speed is slowed down," Nathan said of the effect of air drag. "If it were gravity (only), it would be totally symmetrical."

He notes the vast majority of home runs are hit with launch angles between 25 and 30 degrees. The average since 2020 is 28.8 degrees, according to Baseball Savant, MLB's data portal. No matter the launch angle, all balls hit in the air decline at a steeper angle than they left the bat at, a multiple of 1.5 times of launch angle, according to Nathan.

"To a pretty good approximation, the angle at which the (average home run) descends - which is really what you are looking for here - is about 45 degrees," Nathan said, "which is a very convenient number because the tangent of 45 degrees is one."

With a 45-degree angle of descent, for every foot of horizontal distance covered, there's one foot in vertical drop.

"If you're going to bring your fences in 15 feet, you better raise them 15 feet," Nathan said of the right-center gap. "Four feet simply won't do it."

Rogers Centre already ranked fourth in total home runs last year - trailing only Great American Ball Park (Cincinnati), American Family Field (Milwaukee), and Yankee Stadium (New York).

There were four more home runs hit in Toronto (204) than Denver's mile-high air.

Yes, the Blue Jays have boasted some strong lineups, but the Rogers Centre also ranked fifth in road home runs last season, and fifth in its last three full seasons.

While playing in the AL East inflates totals, the Rogers Centre ranked eighth in home run favorability last season according to ESPN's park factors, which compare the rate of teams' stats to home and the road. It ranked first in 2019 and 12th in 2021.

The Rogers Centre has generally been a favorable environment in which to try and hit a ball over the wall, whether by raw or adjusted totals. And now the outfield is shrinking.

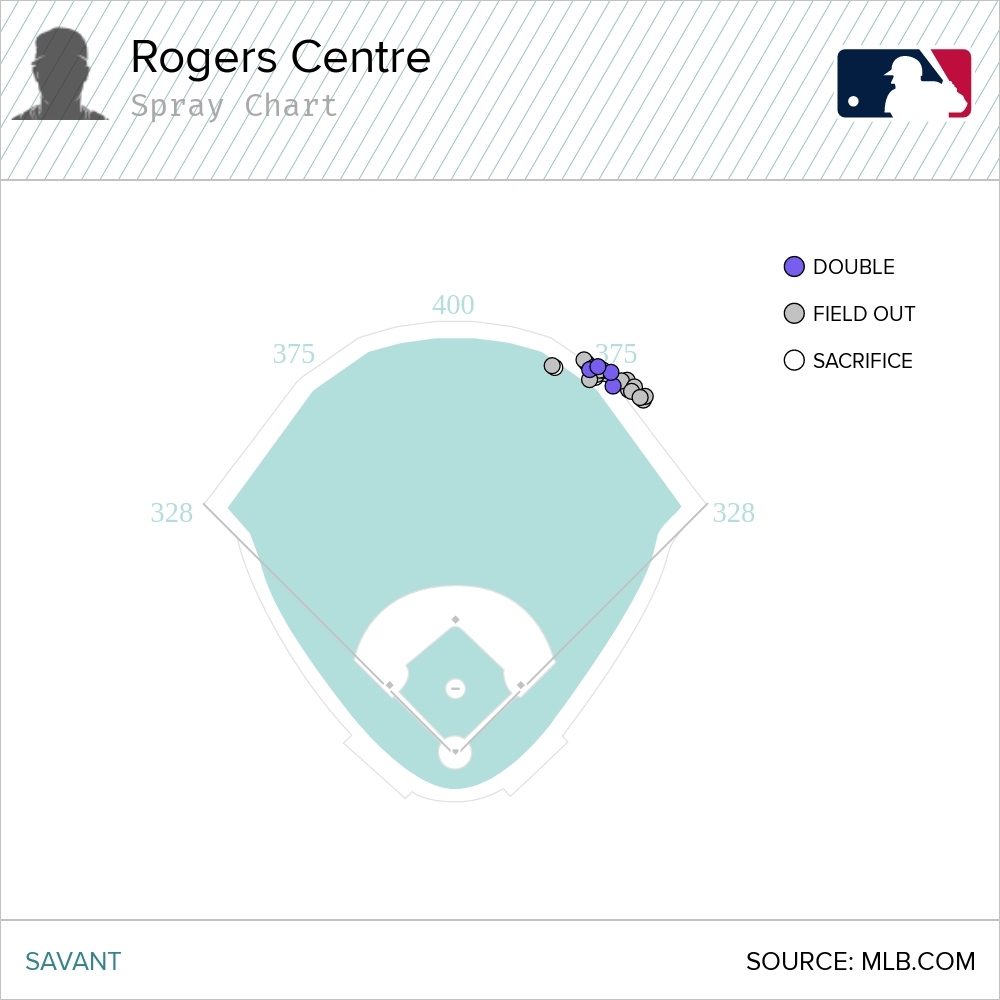

We looked at all fly balls that weren't home runs a year ago that could have been based on the new dimensions. We examined borderline home runs in areas where fences will be raised, and balls hit more than 400 feet to center that weren't home runs with a 10-foot wall but could be with an 8-foot wall.

While Statcast data doesn't give exact coordinates of where a ball passed over the would-be new dimensions, I estimate there would have been a net gain of 15 home runs if last year's balls had been hit using the new dimensions.

The shorter distances would have added an estimated 22 home runs, but the taller fences would have subtracted seven of them.

While 15 isn't an astronomical figure, it would have made the venue the top homer park in the majors last year: 219 compared to 217 at Great American Ball Park. It would represent a 7% increase in home runs for a stadium already favorable to hitters.

The hottest spot is right-center field and the right-center power alley: I estimate 19 fly balls that were either outs or doubles last year would be home runs with the new dimensions. Here's a good example from Raimel Tapia:

While the new dimensions would seem to favor left-handed batters, 31 of the 50 fly balls hit to right field that might be home runs in 2023 were actually hit by right-handed batters.

The Blue Jays had the heaviest right-handed hitting team in the majors last year and the majority of their power remains right-handed.

Consider that Yankee Stadium, with its short right field, has awarded right-handed batters with 111 opposite-field home runs since 2020, nearly double the next closest venue, Houston, with 63. (Left-handed hitters have homered 135 times over the right-field wall at Yankee Stadium.)

Perhaps Toronto's right-handed hitters will benefit similarly.

Of course, the new fence height would have kept some home runs last year in the yard, like the one below by Randy Arozarena, a ball which bounced off the top of the wall and went out. The new 14-foot, 4-inch wall keeps it in play.

Will Toronto become a new launching pad? We'll find out in a few months.

Travis Sawchik is theScore's senior baseball writer.

HEADLINES

- Report: Orioles, Bassitt agree to 1-year, $18.5M deal

- Report: Carroll set for surgery on hamate bone, will miss WBC

- Lindor to undergo hand surgery, could be ready for Opening Day

- Orioles' Holliday to have surgery on hamate bone, will start season on IL

- Royals' Bubic wins arbitration hearing, Blue Jays beat Lauer