A new, old rhythm: How the pitch clock could be profoundly positive

Rule changes aren't new in the lifespan of Major League Baseball.

The mound was lowered from 15 to 10 inches after the so-called "Year of the Pitcher" in 1968 to boost offense. The American League even introduced something as radical as a new position in 1973: the designated hitter.

So new rules coming into effect this season - the adoption of larger bases, a ban on defensive infield shifts, and limiting the number of pickoff attempts - aren't the most radical changes ever implemented.

But the volume of change speaks to an urgency to experiment. MLB wants more action and more athleticism as its attendance continues to decline - nearly 19% from its 2007 peak - and its fan base continues to age.

The sport is also contending with stagnating revenue growth and an uncertain TV rights future. The commissioner's office must do something, so it's going to try lots of things.

One rule change in particular will have the greatest effect on the 2023 product: the pitch clock. The changes it ushers in could be profoundly positive once batters and pitchers get accustomed to the new rhythms this spring.

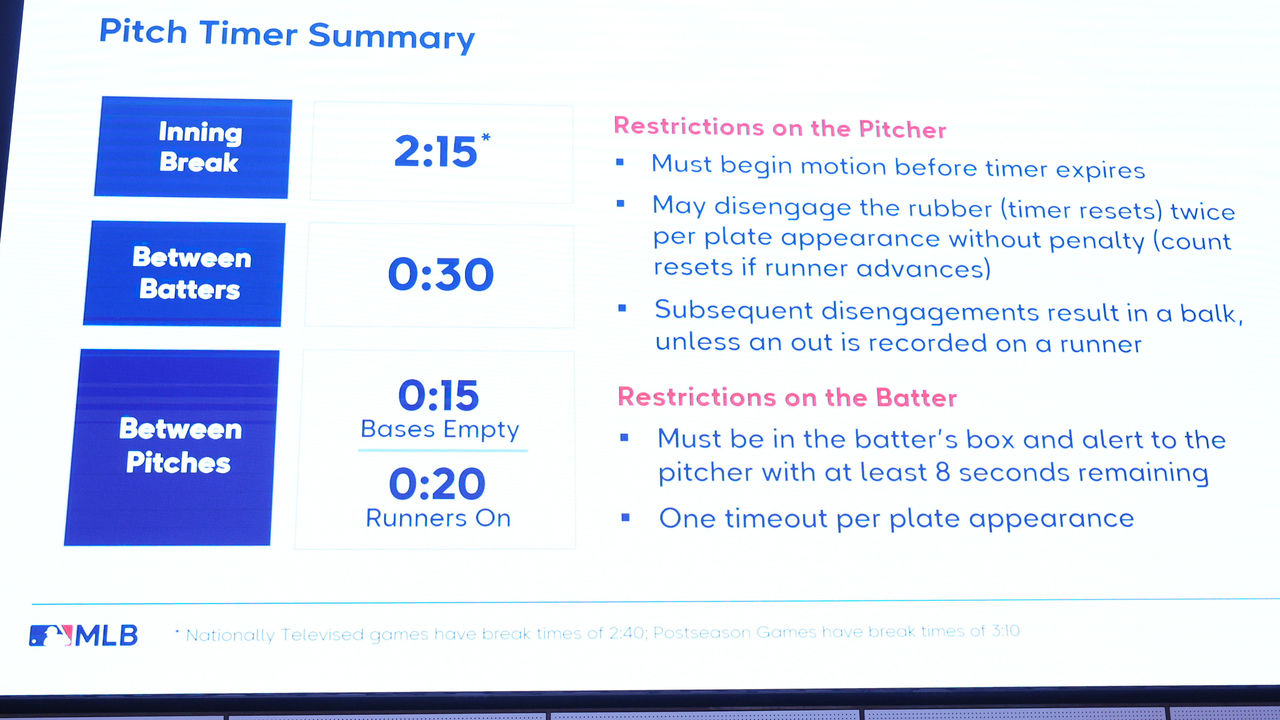

This season, when the bases are empty, a pitch must be thrown within 15 seconds. With runners on, the ball must leave the pitcher's hand in 20 seconds. Batters must be in the box and ready to hit with at least eight seconds remaining. Pitchers in violation of the rule are assessed a ball; tardy batters get a strike.

The impact will be felt throughout the game. Consider that of the 648 major leaguers to throw at least 10 innings last season, only 32 averaged less than 20 seconds between pitches.

The clock is supposed to start when the pitcher gets the ball from the umpire or catcher. Nearly every pitcher except for the Brewers' Wade Miley will have to pick up the pace. He was an outlier last season, working at a 15.5-second pace in his nine outings. Only position players pitching in blowouts averaged less than 15 seconds last year.

Last season, 141 pitchers (22% of those who threw 10 or more innings) averaged 25 seconds or more between pitches.

The worst offenders in 2022 were relievers: Giovanny Gallegos, Devin Williams, and Kenley Jansen; each averaged more than 30 seconds between pitches.

Gallegos is one of the slowest workers on record, averaging 31.6 seconds between pitches in 2021, trailing only Rafael Betancourt in 2007 (31.9 seconds) and Jonathan Papelbon (31.6 seconds) in 2009.

Relievers are slower workers than starting pitchers, and the game's end is where the pitch clock figures to be a more difficult adjustment. Last year, starters needed 22.6 seconds between pitches, and relievers 23.9 seconds.

That time adds up. The total time of games has increased significantly: from an average of 2 hours and 23 minutes in 1972 to 3 hours and 3 minutes in 2022. The average game first crossed the three-hour mark in 2014 and has remained above three hours each season since 2016.

But more than total time per game, I argue that pace, the seconds between pitches, matters more to the actual in-game viewing experience - especially at a time when we're all distracted by the smartphones in our hands.

MLB started collecting pace data in 2007 when PITCHf/x pitch-tracking technology was first installed in stadiums and began time-stamping pitches. Pace has generally been on an upward trajectory since, hitting a record 23.7 seconds in 2021. Pace fell to 23.1 seconds last year, in part because of PitchCom, new tech that sped up pitch-calling communication between catchers and pitchers.

But it's not only pitchers dragging games to a crawl. Batters are arguably greater culprits.

When I was a beat writer covering the Pirates in 2014 for the Pittsburgh Tribune-Review, I started a timer every time a batter left the box with two feet and stopped it when he returned to the box during a Cardinals-Pirates game. In total, batters spent 42 minutes outside the box that night, in a game that lasted 3:37. The same season, Grant Brisbee, then writing for SB Nation, compared two games that had similar box score characteristics - one from 1984 and another from 2014 - and found that the between-pitch pace has slowed considerably.

There's been a lot of Velcroing and un-Velcroing of batting gloves in recent years. Perhaps it's not even fair to call it a pitch clock.

Since the same pace data can be applied to hitters as well as pitchers, we can see which batters are generally the slowest. Mark Canha averaged 27.5 seconds between pitches last year, the most lethargic pace for hitters with at least 500 plate appearances. It was also the eighth-slowest batter pace on record. Two other Mets - Pete Alonso and Jeff McNeil - were in the top five last season. Marcus Semien was the quickest, averaging 20.5 seconds.

The clock should restore a better rhythm to play. It'll move the game closer to how it was played for most of its history.

When the pitch clock was widely implemented at the minor-league level last year, it cut 25 minutes from the average game, reducing them to an average of 2:38.

If that reduction is replicated at the MLB level, it would bring the average game time back to levels last experienced in the mid-1980s.

And it's important. If baseball's games averaged three hours and came with a strikeout rate approaching 25% back in its nascent days, the sport would probably be a historical footnote.

The clock could also have a spillover effect to other areas of game play.

With new pickoff limitations, a clock nearing zero will potentially help some baserunners get an early jump on steal attempts and running on full counts.

We can also anticipate some changes in pitching velocity. Last year, pitchers with above-average four-seam fastball velocities averaged 23.9 seconds between pitches, and those with below-average velocities averaged 22.7 seconds.

Does more rest between pitches allow for more velocity?

In 2017, Rob Arthur at FiveThirtyEight found there was a relationship between more rest between pitches leading to more velocity. If the clock slows velocity, batting averages and run scoring could increase. Slowing pitchers' velocities by speeding up their deliveries could have more impact on offense than anything the shift ban or super-sized bases will do.

Last season, batters hit .252 against 96-mph fastballs - 2 mph above the league average - but .280 against 92-mph fastballs, which were 2 mph below the league average.

That said, there wasn't much velocity loss at the minor-league level last year.

Baseball America reported that fastballs averaged 92.3 mph in the minors, the same as in 2021 before the pitch clock. At the major-league level, average fastball velocity hit 93.9 mph in 2022, which is up from 91.9 in 2008, according to Statcast. Pitching pace is certainly not the only reason for the increase, but it likely has some effect. Forcing pitchers to quicken the pace may at least help stem the rising tide of fastball velocities gained through advancements in training and technology.

Given the lack of innings thrown by minor-league hurlers - only five minor leaguers exceeded 150 innings last year - perhaps stamina will be more tested at the major-league level with the clock.

A total of 313 major-league pitchers logged a minimum of five innings in both 2021 and 2022 and also decreased their pitching pace between seasons. That cohort actually added an average of 1.02 mph to their fastball velocity. So, perhaps adjustments can be made that will help maintain velocity despite losing rest time. We'll have to wait and see.

As society moves faster, as smartphones constantly distract, as free-flowing sports like soccer and basketball have gained popularity, baseball must quicken its pace to remain culturally relevant as a mass-appeal entertainment product.

Without a shot clock and 3-point line, basketball would be a different game, and perhaps the NBA's popularity wouldn't have exploded. Sometimes drastic changes are needed. MLB is right to be experimenting this year, and among all its tests, the pitch clock is most needed and will have the greatest impact.

Travis Sawchik is theScore's senior baseball writer.