MLB should embrace the Bally's crisis and forge its next TV path

One of Sinclair Broadcast Group's most important marketing and advertising partners told theScore a year ago there was no chance a major pro sports league could launch a direct-to-consumer product any time soon.

It would be impossible to gather the local TV rights - both cable and streaming - because they're scattered around the media ecosystem and expire over a myriad of timespans.

"It's not like someone can say, 'I'm going to take all the local rights in the U.S. back' any time in the next 20 years," Michael Schreiber, the CEO of PlayFly Sports, said at the time.

Now, MLB might not have a choice. When new technology disrupts a business model, change can happen fast.

Earlier this week, Sinclair's Diamond Sports Group subsidiary declined to remit a scheduled $140-million debt payment on its $9-billion debt. That triggered a 30-day grace period, at the conclusion of which the company is expected to file for bankruptcy. Its 19 regional sports networks (RSNs) have become underwater assets due to cord-cutting less than four years after Sinclair purchased those Fox Sports channels from Disney.

The fallout will affect the NBA, NHL, and MLB, all of which have teams with ties to Diamond's Bally Sports-branded RSNs. It was reported that the NHL board of governors met Wednesday to discuss the issue, and the league issued a tepid statement Thursday saying it's "closely monitoring the RSN situation." On the cusp of a new season, 14 MLB clubs now face uncertainty regarding the future of their local TV rights. Many of those clubs are due payments from Diamond before Opening Day.

What's clear is the cable model is failing, and it's been exacerbated by Bally's debt problems. For MLB, it's time to take control of as many of its local rights as possible and follow a Netflix or Disney+ model.

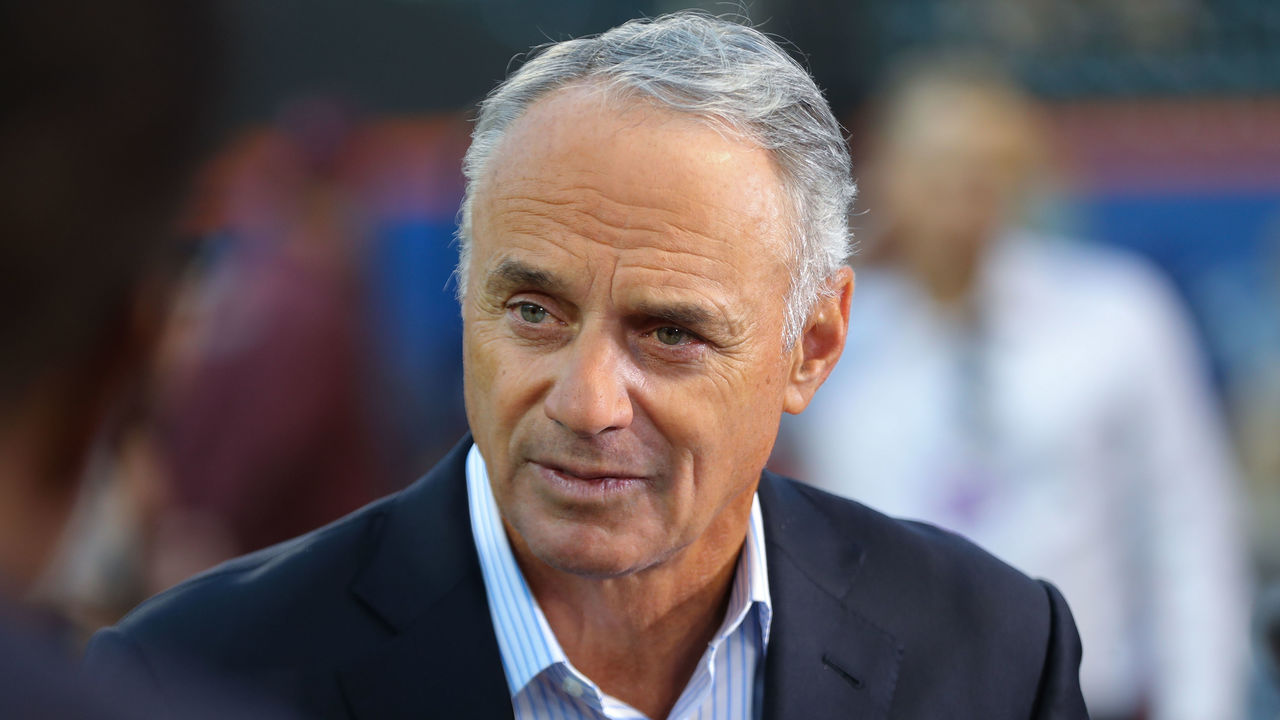

MLB commissioner Rob Manfred said Wednesday that affected MLB clubs will terminate their agreements and reclaim their in-market TV rights if Diamond fails to make its rights payments.

If the teams take back rights, Manfred said MLB will produce the games and attempt to sell them directly to cable providers. But he added that in-market games would also be distributed through MLB.TV, MLB's existing direct-to-consumer platform.

While MLB.TV already distributes every game, only out-of-market viewers can currently watch them. An in-market option would open a new frontier for a league often criticized for its blackout policies.

"You can buy your out-of-market games like you always have, but you have the option to buy up into in-market games, which I see as a huge improvement for fans," Manfred said of the contingency.

Manfred admitted, however, that such a model wouldn't generate enough revenue to offset Diamond's debts to clubs.

"Not in the short term," he said.

Through a crisis can come opportunity, and this might be the catalyst to transform MLB's distribution. There may be short-term financial pain, but it could put the league on the path to something more profitable in the long term.

Manfred is still hoping the cable model can stay afloat for multiple years.

"Eventually, it might go away. But I don't think it's a short-term phenomenon," he said. "I think it's really important for the game to preserve the economics in the remaining RSN-cable bundle while developing a digital alternative that has more flexibility and gives us better reach."

But that timeline might be wishful thinking. The U.S. cable subscriber base is down 30% from its peak in 2014, and the losses are accelerating. While MLB has sold in-market cable and streaming rights separately, it's the streaming rights that are key long-term.

Consider what Jeff Green, CEO of The Trade Desk - the leading advertising platform on the open internet (which includes connected TV) - said during the company's conference call Wednesday.

"The shift from linear TV to (connected TV) continues to accelerate, and I predict that, at some point in the near future, we will reach a precipitous tipping point," Green said. "It won't be a long, gradual shift to CTV. It will be an acceleration and then a full-on shift."

Roku, the top streaming platform that controls about a third of the market, also announced earnings this week. It reported streaming hours on its platform grew 23% in 2022.

Comcast, meanwhile, recently announced that its cable subscriber count declined 11% in 2022.

Not only are subscribers fleeing from cable, but so are advertisers. TV connected to the internet can better target customers, is richer in data, and provides a better return on investment than ads on linear cable.

But there's opportunity here, too, Green noted, for owners of premium content; he told analysts that advertisers are shifting spending "from user-generated content to premium streaming content."

Long term, MLB distributing more of its own games - and owning its ad inventory directly - could be beneficial.

A direct-to-consumer product would also allow MLB to better target a younger audience, something it's struggled to do.

Going direct ends most blackouts and eliminates the need for so many subscriptions, which would be far more consumer friendly.

But there's also the matter of rounding up enough rights for a robust DTC product. The 14 Bally's teams would be a good start.

And while individual teams could opt for their own direct-to-consumer, in-market products, there is a strength in numbers from tying as many teams' rights together as possible. That could lessen risk depending on how revenues would be shared.

Yes, there are plenty of risks. Owners may balk at a DTC model because it lacks guaranteed checks from broadcast partners. More teams will have to compete in order to drive subscriptions. Changing the TV revenue landscape would create revenue-sharing issues among teams and necessitate negotiations with the players' union.

But MLB clubs are mistaken if they think there's a future in cable. If MLB doesn't want to forge its own path, the alternative is a new third-party distributor for in-market games. That might not be so easy.

MLB moved in that direction last year when it replaced a deal with ESPN for midweek games with a series of agreements that included ESPN and streamers Peacock and Apple TV+. That combined package of deals brought in about $35 million less than MLB made with ESPN alone.

The NFL moved its Thursday Night Football games to Amazon this season and sold the distribution of its U.S. Sunday Ticket package to YouTube starting next season. Beyond the Bally's crisis, the next major TV property to hit the open market will be the NBA's national rights collection in 2025. The tech giants have been lukewarm on MLB thus far.

MLB became a pioneer in streaming when it created its digital wing, MLB Advanced Media, in 2000. MLB streamed its first game in 2002. The league later spun off its streaming tech division, BAMTech, and sold it in chunks over time to Disney for a combined $3.5 billion. That technology became the backbone of Disney+, Hulu, and ESPN+. MLB can, and perhaps must, be a pioneer again.

Travis Sawchik is theScore's senior baseball writer.

HEADLINES

- Machado wishes more teams spent like Dodgers: 'I f-----g love it'

- Harper: Dombrowski's review of 2025 season is 'kind of wild to me still'

- Red Sox exec Kennedy: If 'Bregman wanted to be here, ultimately he'd be here'

- MLB offseason: Analysis for all major moves

- Braves' Waldrep undergoing tests after loose bodies found in arm