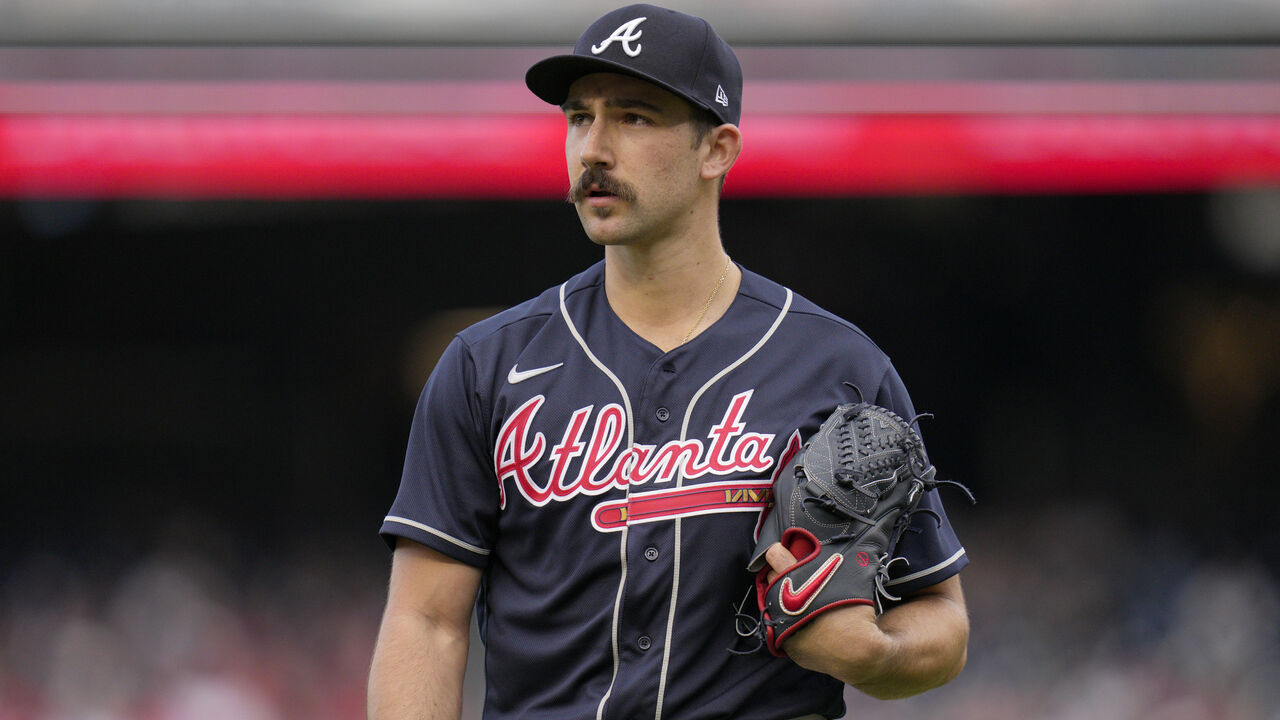

How Spencer Strider developed a cheat-code pitch to become an unlikely ace

NORTH PORT, Fla. - The pitch is essentially a laser beam.

Spencer Strider's top-of-the-scale fastball, an 80-grade offering on baseball's 20-to-80 scouting scale, is one of the best pitches in the sport.

Since the start of last season, batters are hitting .194 against his fastball compared to the league average of .254. The pitch's runs-saved-above-average value ranks second. And this despite his four-seam fastball usage (65%) ranking 15th among all pitchers to throw at least 500 pitches since the start of last season.

Hitters know it's coming and they still appear helpless.

What allows it to be such a weapon?

"The hardest thing for a hitter to do is decide when to swing: when and where," Strider told theScore in late March. "The closer the release is to home, the less movement it needs to be difficult to predict where it's going. I think with good extension, lower release height, and I think my ball rides well, it all just packages to be deceptive."

He's basically built Jacob deGrom's fastball in terms of its speed, release point, and shape.

But unlike deGrom, Strider possesses an unlikely pitching build: he stands just six feet tall. He's the game's most unusual ace. He's short in relative terms, and he's also a vegan, a diet change he made while at Clemson University. He's a dedicated hipster. In a Google doc, he created a ranking system for Indie rock albums. He wears No. 99 - the number of fictional pitcher Rick Vaughn in "Major League," his favorite movie - and a mustache instead of a beard, which he says makes his face appear too rounded.

And he's unusual, too, because he throws only two pitches. He can do so because his fastball is that good.

In 2022, Strider produced the third-highest strikeout rate in baseball history (38.5%) among pitchers to log at least 100 innings in a season - behind only Gerrit Cole (39.9% in 2019) and Chris Sale (38.4% in 2018) - and best for a pitcher six feet in height or shorter, surpassing Pedro Martinez's mark in 1999 (37.5%).

He's struck out nine or more batters in nine straight outings - only Sale (10 in 2018) and Nolan Ryan (11 in 1977) have longer streaks. He struck out 13 Marlins over eight innings Monday, taking a perfect game into the seventh inning. Strider's 2023 strikeout rate is an obscene 42.6% - it would be a record.

What's interesting is how these performances, keyed with this overpowering fastball, were created.

Strider wasn't gifted an elite fastball.

He didn't possess this fastball as a senior in high school in Tennessee. His heater sat in the low 90s when he was a 35th-round pick by Cleveland in 2017.

"His fastball doesn't show much life and he currently doesn't have a solid out pitch," Baseball America wrote at the time.

He didn't have his fastball as a freshman at Clemson, either.

Driveline Baseball's director of pitching Chris Langin says an elite four-seamer is typically difficult to engineer.

"You cannot really teach it," Langin said. "The four-seamer, of all the things pitch-design wise, it's probably the hardest pitch to teach."

Yet Strider learned it. He drew up a plan and created it - with help - all because of a setback many would view as devastating.

Cory Shaffer is a sports psychologist at Clemson University. He meets with the baseball team once a week and holds voluntary one-on-one sessions with student-athletes. Strider didn't visit until he tore his UCL in his right elbow in the spring of 2019, on the cusp of his sophomore campaign. Tommy John surgery followed.

In their first talks, Shaffer wanted Strider to apply a different kind of mindset to his rehab. He saw other athletes sharing news of an injury on their social media accounts that often went something like this: "Thanks for all the support. Despite this, I am going to come back better than ever," Shaffer said.

"The analogy I always use is: imagine writing a book about the story of yourself in baseball. That kind of mindset, 'despite this injury,' it's almost like you leave that chapter out. It's sort of a footnote," Shaffer said. "The mindset I encouraged him, or anyone to have is: 'No, because of this injury I will come back better than ever.'

"So now if you are writing that same book, it's a really important chapter. It might be the longest chapter in the book. So much happened in that chapter."

Shaffer stressed that from the time Strider picked up a baseball, he never had the time to have to develop himself, and he was about to have a lot of it.

"You are a blank canvas," Shaffer told Strider. "There is a massive opportunity in front of you."

He would have a year to not worry about competing for a spot or making adjustments in the middle of the season.

"Getting hurt in some ways was a good opportunity to do these things that I couldn't have done otherwise," Strider said. "That opportunity to build from the ground up was sort of a blessing in disguise."

Strider decided to rebuild his delivery.

He didn't go to Driveline or another facility to learn concepts and take advantage of their tech; he researched and taught himself instead.

"It was a bit of surfing the internet, YouTube," Strider said.

He had questions: How do the best pitchers who are built like me move? What do the best pitch characteristics look like? How do pitchers add velocity? He tried to answer them.

He didn't have a body like deGrom or Cole, so he didn't bother studying those archetypes.

Rather, in the spring of 2019, he looked at how Trevor Bauer and Walker Buehler moved in their deliveries. They were sized like him and threw four-seamers.

"I really started to look at data and try and figure out what guys' best stuff was," Strider said. "It was clear early that I had good ride and carry. I needed to try to pitch at the top of the zone, and pitch above guys' barrels, rather than see the ball move … previously we thought the more it moved, the harder it was to hit."

To make his fastball play up, he learned he had to get down the mound faster, cover more distance, and create more energy.

More than anything, Strider needed a better stride.

"Extension, release height, velocity, and movement are all connected," Strider said.

He explains: If your move takes you further down the mound, you'll likely lower your release height, and create more energy by moving faster.

"But if you increase extension, you need to block better with your front side so that you rotate fully around. And then to do that, you have to drive better with your back leg," he said. "Which means you have to stay longer over the rubber. They are all correlated."

That plan led to the dominant pitch we see today.

Velocity is a key characteristic of Strider's fastball, of course. His average velocity since the start of last season, 98 mph, ranks behind only Hunter Greene and deGrom among starters. But velocity isn't the only meaningful trait.

There is the extension of his delivery, or how closely a pitcher releases the ball to home plate.

Strider's extension of 7.08 feet ranks in the top 20 in the game this year, and the starting pitchers ahead of him, like Logan Gilbert and Bailey Ober, are at least two inches taller than the 6-foot Strider.

The longer the extension, the less distance the ball travels and the faster it appears. That's known as perceived velocity. The only starter with a greater perceived velocity than Strider's (98.4 mph) since the start of last season is deGrom (99.5 mph).

Then there's the pitch's release height. The lower the release height, the better for a four-seamer. Why? Langin explained.

"Pitchers that have lower release height, and that can generate any type of carry (or rising effect), they are the ones who are generally going to be the ones that kind of surprise guys with vertical break," Langin said. "Whatever you want to call it: vertical approach angle, or how flat that fastball is, it really helps that fastball play up."

Since the start of last season, there are two pitchers with four-seamers that average 98 mph or better that also possess below-average release height, above-average extension, and flat vertical approach angle of five degrees or less: Strider and deGrom.

"I want to say the two guys who compete with him are (Tyler) Glasnow and deGrom," Langin said of the top four-seamers among starters. "The main ingredient is their absurd velocity. But (Strider) also has the unique four-seam vertical break, especially when you account relative to his release height.

"You could look at a CSV file and determine this guy has a pretty damn good fastball."

Strider's fastball possesses every attribute one would want in the pitch including above-average rise - 2.6 inches of relative vertical rise, 21%, superior to the MLB average.

To put all this together, after adjusting his mindset and creating his own plan, Strider needed to execute the plan and build a stronger foundation.

In spring 2019, Strider handed his remodeled delivery plan to Rick Franzblau, director of strength and conditioning for Clemson athletes who compete in sports that are offered at the Olympics.

The plan's goals were "to get further down the mound, to lower my release height, and stay behind the ball," Strider said. As a freshman, his average extension was an even six feet according to TrackMan data supplied by an MLB club.

Franzblau was struck by the detail from a newly turned 21-year-old.

"He took it upon himself, with his own intuitive and cerebral sense, and kind of modeled a lot of his delivery based upon similar body structures," Franzblau said. "We reverse engineered from there, based on what he needed from a physical perspective, to be able to get in those positions, and repeat them pitch to pitch, outing to outing."

Strider required a stronger base - stronger legs - without losing athleticism in order to create what he wanted, Franzblau assessed.

He needed to create a great push off his right leg to move faster and further down the mound and be strong enough to stick his landing leg efficiently and transfer the energy from the ground to his hand.

For the first eight weeks after the surgery, pitchers can only use their own body weight in exercises, so they were limited to isometric options.

"I put him through this grueling long-duration isometric program where the goal was to hold a three-minute lunge position, isometrically," Franzblau said. "He got up to it."

There were wall squats, too. "His whole session might be five or six reps of (wall squats)," Franzblau said.

This rehab was not designed for enjoyment. Already strong in his lower half, as many pitchers are, Strider became stronger.

As spring turned to summer, he remained on campus to work with Franzblau. They began adding weight to the work.

Strider advanced to lifting 355 pounds for three reps on a reverse lunge. For reference: one rep of 320 pounds is considered advanced for a 190-pound male; 399 pounds is elite. They worked to the maximum weight they could manage without putting his body in positions that tilted his pelvis too far to the ground, Franzblau said.

"For a shorter guy to throw hard, you're going to have a hard time finding a guy who doesn't have some pretty good weight-room prowess," Franzblau said. "A shorter guy, to create some of the ground forces and kinetic energy necessary, generally speaking, is going to have to be a stronger individual."

Said Shaffer: "There's a reason they call him 'Quadzilla.'"

Building strength was important, but so was maintaining athleticism and flexibility to ensure "that as we're getting stronger, we're not turning into a block," Franzblau said.

Franzblau taught Clemson pitchers like Strider mobility drills for hip rotation. He incorporated other exercises into Strider's regimen including sprint work, agility drills, and hurdling.

Spencer Strider started doing the exercise in his viral hip mobility video during his Freshman year at @ClemsonBaseball. They're called hip "CARS."

— Lance Brozdowski (@LanceBroz) June 17, 2022

Credits Clemson strength coach Rick Franzblau.

On @PitchingNinja's "quadzilla" nickname: "I'm proud of my quads." #ForTheA pic.twitter.com/0ye2R3bUSo

He'd arrange three track hurdles on a 30-meter stretch of indoor turf.

As Strider and the other rehabbing athletes who sometimes worked together improved at clearing the hurdles, Franzblau shortened the distance between them. He also made them alternate lead legs.

"It challenged them from a movement perspective," Franzblau said. "They failed a little bit and it was frustrating." But that was intentional. "They had to deal with it."

All that foundational work went toward the linear component of his delivery. He also needed to work on the rotational component.

"I wanted to shorten my arm path, understanding that rotation speed was instrumental in creating velocity and getting down the mound," Strider explained. "If I could stay close together and centered around the core of my body longer, then I could rotate faster."

Think about how a figure skater's spin accelerates when they draw their arms inward. It's the application of the law of conservation of angular momentum, something Strider said he happened to stumble upon.

That shorter arm circle also allowed Strider to better hide the ball from batters, Franzblau and Strider both said.

"He kind of weaponized his fastball," Franzblau said.

In winter 2019, as Strider was throwing bullpens, Franzblau trained an Edgertronic high-speed camera on him. Commonly used in pitch design, Strider also used them to hone his finger placement and wrist position at pitch release to maximize spin efficiency. Franzblau used them for another purpose, though.

"I have Edgertronic video of Spencer, nine, 10 months out (from surgery) on the mound, and you can just see how well that (energy) wave propagates right into his shoulder," Franzblau said.

He uses the footage to teach concepts to student-athletes at Clemson today.

"The ability to accept that energy and propagate it into the area you want (is impressive). With a lot of guys, if they cannot capture good foot position on the front leg, that wave might propose toward their neck, or propagate more toward the lat," Franzblau said.

"I was able to compare him to the rest of the team and he was really, really unique in that capability."

When Strider returned to game action that year, he reached new velocity highs, hitting 97 mph. Atlanta made him a fourth-round pick after only four appearances in the COVID-shortened season.

Throughout 2019, Franzblau preached: "Learn to be your own coach." He reasoned that a professional baseball player might have four different strength coaches and just as many pitching coaches as he moves through the minor leagues to the majors. It was important to understand who you were as a pitcher.

Strider took the advice to heart.

"It's really unique, " Franzblau said. "I haven't had anyone like him in that regard."

Strider continued to refine his delivery in pro ball, where he mapped his delivery in labs and threw off force plates for more objective feedback. He's kept throwing harder and hit 102.4 mph with a pitch last season.

But his next step to stardom had nothing to do with the physical act of throwing a baseball.

What psychologist Shaffer observed about Strider as a Clemson freshman was that after a bloop hit, a missed pitch location, or a missed call, he had trouble moving on. He wanted to be perfect.

After their first conversations about adjusting his rehab mindset, they began focusing on another mindset.

"I had Spencer on our podcast last year. I asked him what was the most important thing you've learned about the mental game," Shaffer said. "For him, it was learning to separate what is in his control and what is not. That was vital for him to understand.

"When he got to college, he was basically like, 'If I'm not perfect, I failed,' which is always why he seemed frustrated and emotional."

Shaffer started Strider on a new daily practice: writing in a journal. Strider still does it, entering his handwritten thoughts into a Google doc where Shaffer can add his perspective, as well.

"The best performers are the ones who are most self-aware," Shaffer said. "If you're not willing to admit, 'Emotions got the best of me there,' or 'Mindset got in the way today,' you're never going to be able to improve. His willingness to write in the journal, 'I don't think I competed well enough today,' that's really powerful stuff. Not everyone is willing to do that. They are going to point to the umpire or the mound in that ballpark instead of, 'It's on me.'"

Strider couldn't control what happened after the ball left his hand. But he could control everything until it did.

Something of a paradox developed.

"The more he tries to be perfect is when he tends to be less so," Shaffer said. "He has even described himself as: 'I'm a thrower more so than a pitcher.'"

Command plagued Strider's amateur career. He walked 6.2 batters per nine innings as a freshman.

But his walk rate has come down at every level of baseball: from 5.4 per nine innings in college, to 3.8 in the minors, to 3.2 as a major leaguer.

Early this season, he owns the fourth-highest percentage of pitches in the strike zone (56.8%) according to Pitch Info Solutions, up from 48th out of 140 pitchers to throw at least 100 pitches last season (52.2%).

The idea of not chasing perfection, of not nibbling at corners of the strike zone, was reinforced by the Braves' player development personnel, who had a simple message for Strider in the spring of 2021 before he rocketed through the system: Trust your fastball in the zone.

"'You're not going to need to fool people,'" Strider said of the message. "'Your goal should be to attack guys in the zone and induce swings.'"

He's thrown 606 fastballs in the "heart" of the strike zone since the start of the 2022 season, according to Statcast data, the second most by volume in all of baseball, trailing only Kevin Gausman. And 22% of all his fastballs are in the middle of the strike zone, also the No. 2 percentage among starters.

For many pitchers, those are costly mistake locations. But batters are hitting .243 against his pitch in that location compared to the .302 MLB average,

The pitch is so good that it makes his slider, which has only slightly above-average break, one of the great swing-and-miss offerings in the game.

#Gameday3D -- Spencer Strider fastball/slider overlay

— David Adler (@_dadler) April 25, 2023

83.7 mph slider (whiff)

98.2 mph 4-seamer (backwards K) pic.twitter.com/NjtCJUSJPS

Strider doesn't even see the need for a third pitch.

"I could throw a curveball with a negative-20(-inch) vertical. I don't know that it would be worth it," Strider said. "It wouldn't induce swings. It wouldn't play off my fastball and slider. It would look terrific on TrackMan, but what would be the point of that?

"You look at deGrom, he has the curveball and changeup, too, but he's throwing both less because the fastball-slider combo is what reduces a hitter's decision confidence the most. That deGrom package with the fastball, a breaking ball doesn't even need to have a depth. It just needs to look like a fastball as long as it can. That's all you really need."

It's all Strider needs. His 80-grade fastball is essentially a cheat code. It allows for a here-it-is, try-and-hit-it approach. It allows him to let go of being perfect yet gets him closer to perfection than he's ever been before.

Travis Sawchik is theScore's senior baseball writer.