'Living in an MRI world': The art and science of imaging and diagnosis

There was one final question as I prepared to enter "the tube," as they call it in the office at Beacon Orthopaedics and Sports Medicine. I was about to have my first MRI, one of the more dreaded acronyms in the world of sports.

"Are you wearing Lululemon pants?" the tech asked.

As I placed my cell phone in a storage locker, I responded hesitantly with an affirmative, "Yeah."

The tech explained: this particular brand of clothing goes through a wash of silver in its production process, with traces of the metal bonded to the fabric. The company uses silver to reduce sweat odor. In an MRI machine, the very powerful magnets will heat up the metal, and some poor patient found out the hard way that the clothing gets hot enough to burn skin.

The pants came off. Hospital-issued shorts were put on.

I then entered the adjoining room, where the MRI scanner - a large plastic-encased cylinder - resided.

Two techs situated me on a table that would slide into the center of the tube. They placed me on my right side, a pillow wedged under my head, with my right arm bent at nearly a 90-degree angle; what is known as a stress position. The focus of the imaging was to be on my right elbow.

As the table was nearly ready to convey me into the chamber, an emergency clicker was placed in my right hand. The tech said one in 10 people panic from claustrophobia upon entering the narrow tube. To have your elbow or any top-half-of-body anatomy scanned, one must enter the cylindrical scanner headfirst.

"It's a bit jarring at first," said James Schafer, one of the radiologists on staff, about entering the tube.

I was here to understand the art and science of imaging. I'd thought radiology was much more science than art: the picture was taken, and the diagnosis was generally clear, ironclad.

But there have been some curious cases this baseball season.

Texas Rangers ace Jacob deGrom was initially diagnosed with elbow inflammation this spring. He later required Tommy John surgery, meaning his ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) was significantly torn.

The initial look at prized Philadelphia Phillies prospect Andrew Painter's right elbow found a UCL sprain, but he's also about to undergo Tommy John surgery.

Oakland A's rookie pitcher Mason Miller was deemed initially to have no structural issues in his elbow and instead had a flexor muscle issue. After a second examination, it was determined he had a mild UCL sprain.

Reds pitcher Nick Lodolo was initially diagnosed with tendinosis earlier this spring. A few days later, he was facing a longer recovery from a new diagnosis: a stress fracture of his tibia.

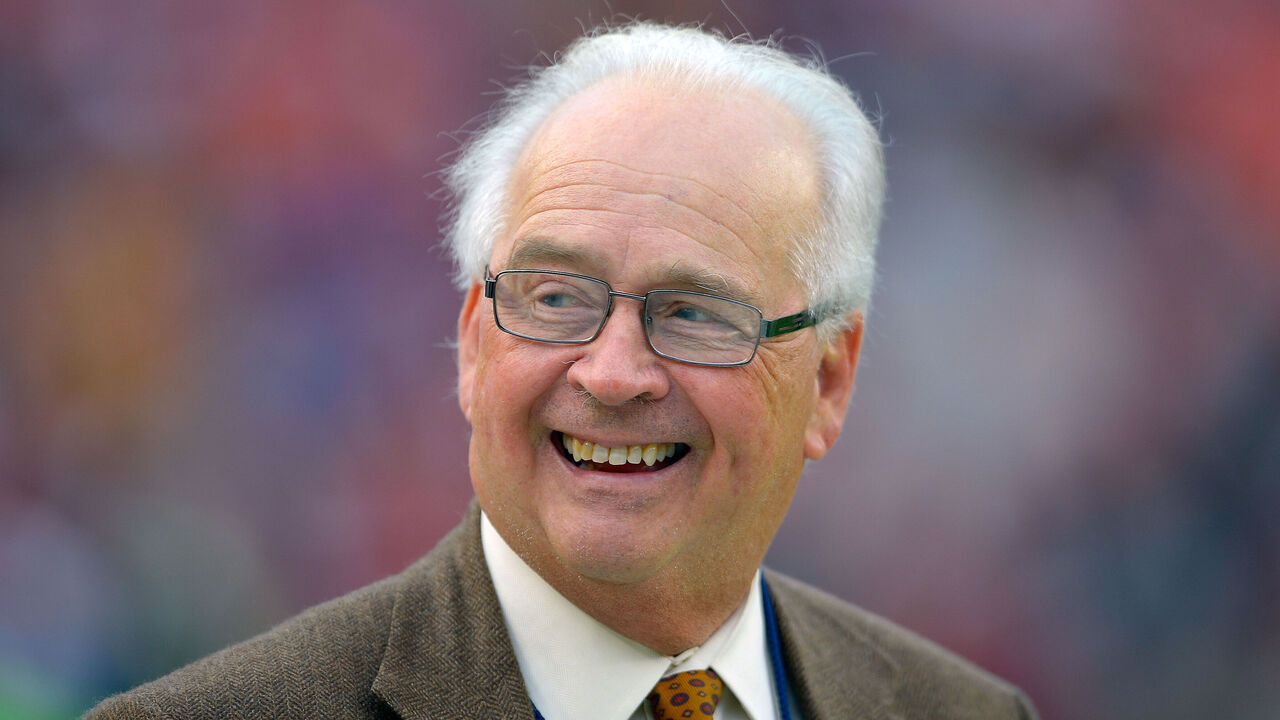

Why are so many initial diagnoses changed? Isn't the MRI the diagnosis tool that stands at the top of the sports medical hierarchy? Are the images not as clear as we believe them to be? I put the question to Dr. Timothy Kremchek, an orthopedic surgeon who served as the Cincinnati Reds' team doctor for 25 years, who founded the facility, and who transitioned to a consultant role with the club earlier this year.

"We're imaging everybody. It's like (former Reds manager) Jack McKeon's classic line to me in 1998: 'Doc, we have more MRIs than RBIs.' The question is, what are we doing with them?" Kremchek said. "How are we using our knowledge as doctors to make decisions on what to do?

"The problem is we're living in an MRI world."

I was about to receive an education. The table began to move along its tracks into the tube.

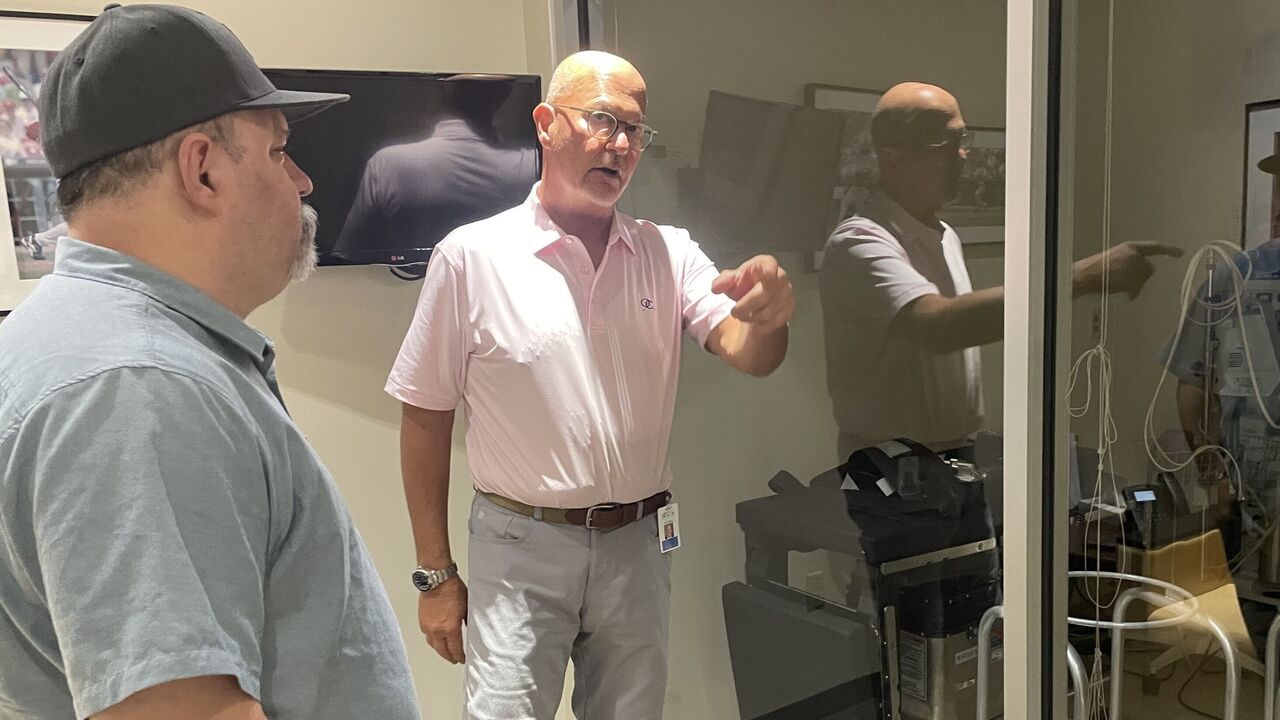

A few hours before I was scanned, Kremchek entered the lobby to meet Will Carroll and I. Carroll is a journalist and sports injury expert, and helped arranged the meeting. Carroll said I had to see this place in my quest to understand the art and science of imaging.

Kremchek wasn't wearing a doctor's white lab coat, but rather a golf shirt. He's tall, trim, and tanned. He sports round-rimmed glasses, and a clean-shaven head removing most signs of gray.

Kremchek doesn't look like he's performing multiple Tommy John surgeries a day, among other procedures, but he is. He tells us he wants athletes to feel comfortable when they enter here; that's part of the reason for his business-casual appearance when greeting folks.

It's also why the place doesn't feel sterile like a typical hospital or doctor's office. The lobby features vaulted ceilings. Adorning the walls are paintings and photos of Reds greats and some signed jerseys. Kremchek joked that if things ever go south here, he'll turn the place into a sports bar.

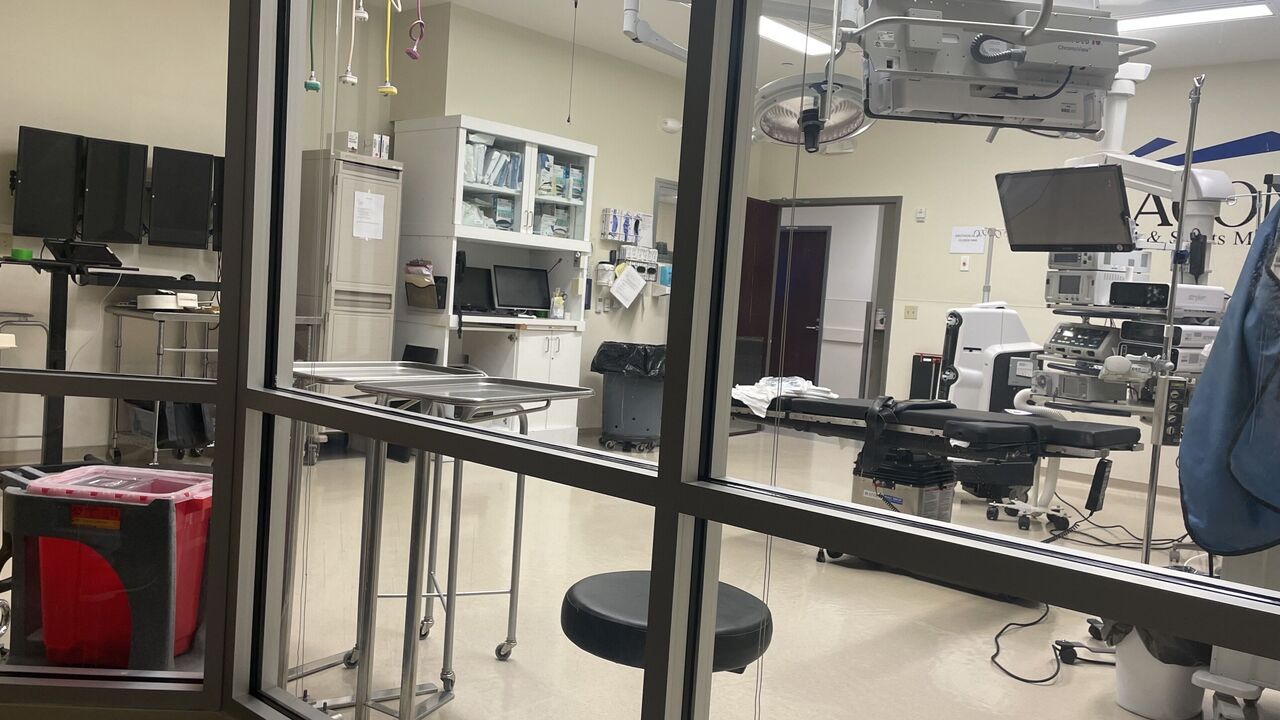

From the lobby, there are corridors to different departments: there's the wing of operating and recovery rooms; a rehabilitation center; and, of course, a radiology department. Alongside one corridor is an indoor pitching mound.

The facility was designed to diagnose, treat, and rehab Reds players under one roof. Kremchek, who's served the Reds and their affiliates for 27 years, believes a fully integrated facility is incredibly important.

For most professional athletes, imaging is often done at a facility separate from the team doctor's office. Surgery would likely be performed at yet another facility. Carroll suggests there are only four other facilities like this in North America. Housing all these services under one roof allows for better care and less risk of error, Kremchek says.

"It's all about that full circle of care," Kremchek said. "Most places are very fragmented. MRIs are read off to the side by people the doctors don't know. To do what I do here, if you don't have all this here, it doesn't work."

From the lobby, we start the tour.

While the lobby is Reds-focused, the hallways to the other districts of the facility feature signed jerseys and photos from other clients.

There's a Denny Neagle-signed jersey as we enter the large rehabilitation space the size of a small college basketball gym, where a handful of athletes and therapists are working together in rehabbing from various procedures. There's an anti-gravity treadmill and a Proteus, a device that measures strength in certain movements.

We move down another hallway, and peek into a recovery room where Blue Jays pitcher Chris Bassitt once rested after Tommy John surgery. We then advance to the operating rooms.

Kremchek ranks sixth all time in the number of Tommy John surgeries administered to professional baseball players, according to Jon Roegele's Tommy John database. Only James Andrews, Keith Meister, Lewis Yocum, Neal ElAttrache, and David Altchek have done more.

When including amateurs and professionals who haven't been documented, Kremchek says he's closing in on 3,000 Tommy John procedures.

"(Alexis) Diaz, our closer for the Reds," Kremchek said. "He came in, his shoulder was sore. I didn't even remember I did his Tommy John when he was in the minor leagues. He was offended, and I was embarrassed. Just another one on the conveyor belt that came through in 2016 or whenever it was."

We eventually enter a space to sit and talk in what is another unusual feature of the facility: an observation room separated by a wall of glass, where one can watch an operation in comfortable seats.

In the operating room is a padded operating table, and affixed to it at a right angle ominously protrudes an armrest at a 90-degree angle. That's where the Tommy John surgery takes place. This table is arranged for a left-handed pitcher.

Kremchek created these rooms to have full transparency during operations for families and agents. He explains through an intercom speaker what he's doing, and what he's found after making an incision.

Most Tommy John surgeries involve taking a similar ligament from another part of the patient's body and replacing the torn UCL in the elbow. A new kind of fix is being undertaken in some cases, where the existing UCL is repaired and braced. San Francisco 49ers quarterback Brock Purdy had this procedure performed by Meister in March, which can offer a shorter recovery time. Purdy was cleared to throw without any restrictions at the start of training camp in late July.

What's helped guide Kremchek and other surgeons for more than three decades on these decisions is the MRI.

Kremchek, though, believes imaging has become a crutch.

"We think the MRI is the ultimate tool. But the MRI is a tool only. It's the experience, (patient) history, and physical examination that helps you with the right diagnosis," he explains. "That's why they are often over- or under-treated.

"We are trying to make too many decisions (from MRIs). And too many people who are uneducated are making decisions, too many people who just read MRIs or scans are making decisions on how to treat these players. We're taking diagnoses, quite often, from radiologists. We're not putting those histories and exams together anymore. We're just like, 'Get a scan, send the scan out to two people, and see what they would do.'"

He gives examples.

"Internal impingement of your shoulder - you're not going to find that in an MRI," Kremchek said.

"Dr. Yocum told me years ago that (on) 40% of Tommy Johns he did - 40% - the MRIs read as normal. Now, if you listen to (the athlete), they hurt, there's pain, there's pain when you stress them, the ligament is not working right, but the MRI shows the ligament is there. If you send that MRI to someone else, they are going to say: that's a normal ligament. He's fixing a ligament because it's not right, while a guy who is reading it in Minnesota or somewhere says it's fine. So, who is right?"

Sometimes the only way to know for sure is to operate and explore.

MRI error can work the other way, too, in creating false signals.

Early last decade, Andrews, who's performed the most Tommy John surgeries, suspected MRIs were creating a lot of noise in addition to proper diagnoses. He had 31 healthy pitchers agree to have their shoulders scanned and found the MRIs showed cartilage and/or tendon abnormalities in 90% of cases.

"If you want an excuse to operate on a pitcher's throwing shoulder, just get an MRI," Andrews told The New York Times for a 2011 piece headlined, "M.R.I.'s, Often Overused, Often Mislead, Doctors Warn."

Kremchek agreed there can be too much noise. "Especially when you are dealing with throwers, who are dealing with elbows and shoulders that have all kinds of junk in there that could be red herrings," he noted.

The last thing a surgeon should want to do is operate on a player who doesn't need it.

Kremchek greatly values radiology. They have a 1.5-Tesla MRI scanner here, and about all the imaging equipment one with pain could ever want to help with a diagnosis.

Beacon also employs its own radiologists to keep the diagnosis circle tight. Schafer and Sunil Misra, who I also meet, work alongside Kremchek each day. There's no telephone game here in relaying findings from imaging. Kremchek and the radiologists learn from each other.

He stresses his point is about the MRI being a great tool, but it cannot alone identify and provide a diagnosis. And I'm about to find out why. Kremchek makes me an offer regarding the machine: "You want to go in?"

A few hours later, after our tour and conversation, I'm being conveyed into the tube. The table is moving.

I thought I'd be in utter darkness in the tube, but it was bathed in a soft, ambient light. As I entered, the space was tight, but any claustrophobic fear was eased since I had my squeeze alarm. If truly necessary, I felt I could manage to wiggle out of the cylinder.

I learned a big test was keeping still.

To acquire the necessary images, the MRI process can take half an hour. An MRI is different from an X-ray, which requires a fraction of a second to extract an internal image. The MRI scanner takes hundreds of images and from different angles.

"We are asking a lot of people to lay down on their back with their arm at their side, or knee, or shoulder," Misra said before I entered the tube. "A lot of the time, these folks are in pain."

I wasn't injured, and I was only in the tube for 20 minutes. Yet only a few minutes in, my right arm was becoming numb, and I was becoming uncomfortable. I wanted to move it. I really wanted to adjust. But I couldn't. I remembered what Misra told me.

"You have to hold really still because each picture takes a decent amount of time to acquire," he said. "You get a little bit of motion in that picture, and the picture is not as crisp as it could be. Kind of like if you are watching 'The Blair Witch Project': 'Oh my gosh, everything is moving all over the place.'"

Remaining still is on the patient, but the techs also must align the elbow correctly. And if the scan is being done at a clinic more accustomed to imaging different parts of the body, that can be an issue. As Kremchek warned before I went into the machine: "You don't do the proper positioning for a UCL ligament and you've missed the tear."

Miller, the A's pitcher whose diagnosis changed, said he went in the tube for his initial scan in what is called a "Superman" pose, lying chest down with his right arm extended forward.

"That one showed no structural damage or anything, just a bunch of edema," he said.

Edema is a term for fluid that can collect around tissue, which shows up as blotches of white on an MRI image.

When Miller flew to Dallas for a second opinion eight days later, his elbow was in the 90-degree stressed position. He said the swelling had also subsided a bit. The diagnosis changed.

"The diagnosis wasn't terribly different. It was more the timetable to return," he said. Miller's now throwing from flat ground in his recovery. "It wasn't anything that was an issue. Most pitchers have micro tears in their shoulder or elbow."

Each imaging sequence can take a handful of minutes. Miller said he had no issue remaining still, so blurring from motion wasn't a problem. For me, it was a challenge.

The other thing I learned about getting an MRI: it's loud.

Before entering, I had to fill out a waiver and document any medical history. Near the end of the form, there was a question about which Spotify channel I wanted played through noise-canceling headphones. The music is there to soften the machine's clamor.

I ask: "What's the most common music people request?"

"Classic rock," the receptionist says. "Taylor Swift is probably second."

I write "Taylor Swift" in the blank space.

In the tube, a computerized voice let me know how long each image round would take. About 10 minutes in, the voice let me know another three-minute cycle was set to begin. The machine started its jackhammer-like chorus again. Another Swift track began, and I hoped it was three minutes long and used it as my gauge. Another arduous three minutes.

Here's what happens in an MRI tube: a magnetic field is created around the patient, causing the protons in the water of the patient's tissue to align with it. MRI machines are cataloged by the strength of their magnets. In a hat tip to Nikola Tesla, whose discovery of the rotating magnetic field in the late 19th century was the first step that would lead to the MRI (and electric motors), the strength of a magnetic field of an MRI machine is measured in Tesla units.

Once a magnetic field is created, radio waves are then pulsed through the patient, and the protons change position. When the radio frequency is turned off, the protons move back into alignment, and the MRI's sensors capture the energy released by the protons, which is converted into images.

The loud noise is from gradient coils encased in the machine. The switching of currents through the coils causes them to expand and contract rapidly, which results in a loud clicking noise.

Misra explains it as simply as he can: "Your body is essentially full of water. Water can be magnetized by this giant magnet, and we start taking pictures."

By the time I entered the tube, athletes' injuries had been imaged regularly for more than 30 years.

The first MRI images of a human were taken in 1977, and the first commercial scanners began being produced in the early 1980s. The focus was on cancer diagnosis but it expanded to sports medicine.

The earliest reported MRI results of a baseball player in The New York Times' archive were for Don Mattingly in 1987, to help diagnose a confounding back injury.

MRIs weren't widespread until the 1990s. For instance, former big-league pitcher and manager John Farrell felt something "pop" in his right arm in 1987 but didn't have his first MRI until 1990, when he was astonished to learn he'd been pitching with a torn ligament.

As the technology proliferated, doctors for the first time could see inside the body to examine soft tissues. In part as a result, Tommy John surgeries skyrocketed. Careers were saved.

From 1974-89, there were 21 Tommy John surgeries performed on major leaguers, as documented in Roegele's database.

In the 1990s, that jumped threefold to 63.

Back in the scanner, as I neared the limit of my ability to remain still, the tech's voice arrived in my headset in a crackle: "Almost done."

Relief. A few minutes later, there was overhead light at the end of the tunnel.

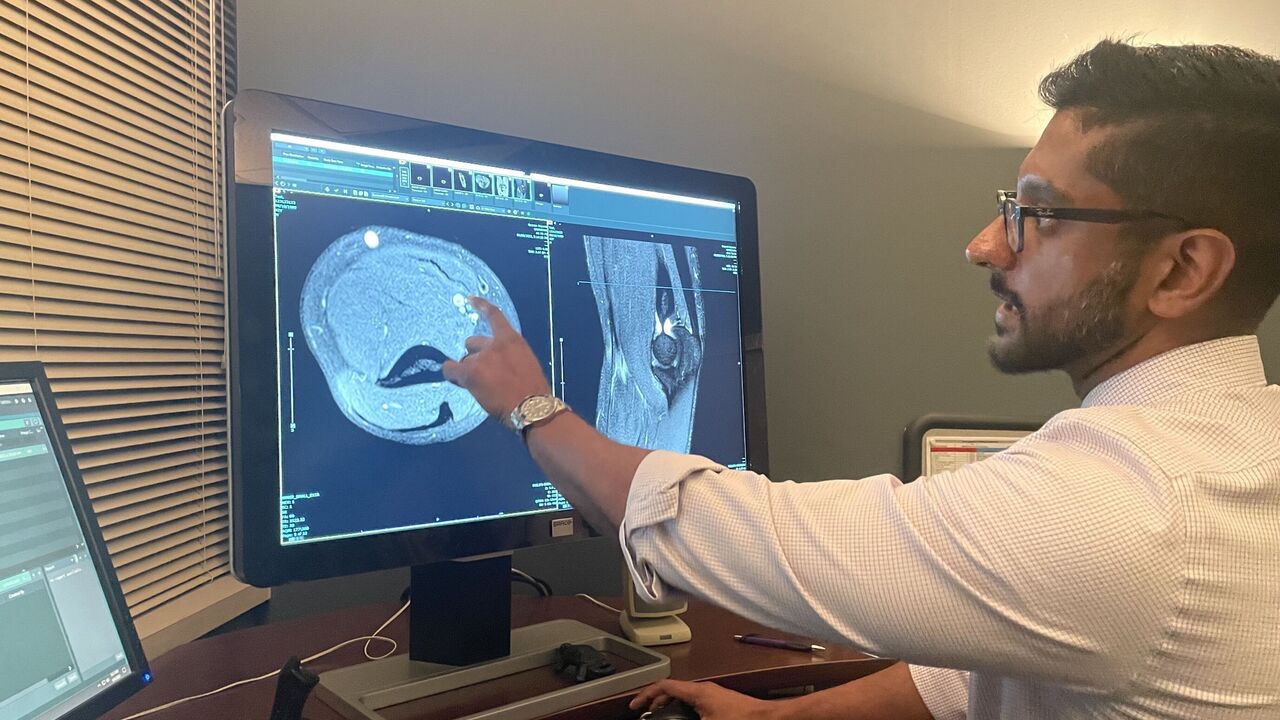

In a room adjacent to where the MRI scanner is housed reside several flat-screen monitors atop a desk where Misra and Schafer examine images.

The room is dimly lit, almost like a movie theater before a film begins. There's a large window looking into the room with the scanning equipment. If they feel an elbow or knee needs to be positioned differently, they can alert a tech. It's another advantage of having everything under one roof.

Misra begins looking at my images. Structures of muscle and tendon begin to appear on the screen as shapes of gray and white blotches. It looked something like a photo negative of a Rorschach test.

I was curious if I'd moved too much, if I'd distorted the images.

"They're pretty good," Misra said. "But you're going to have to take my word on it. There was a little bit of motion. Not much. Like a one out of 10."

Misra begins explaining what we see.

"This is your humerus, your biceps, this is your triceps," says Misra, taking me through a tour of my right arm as he works toward the elbow.

Now the big question: "Is it torn?" Schafer asks, feigning trepidation. We all laughed.

"It's not," Misra said.

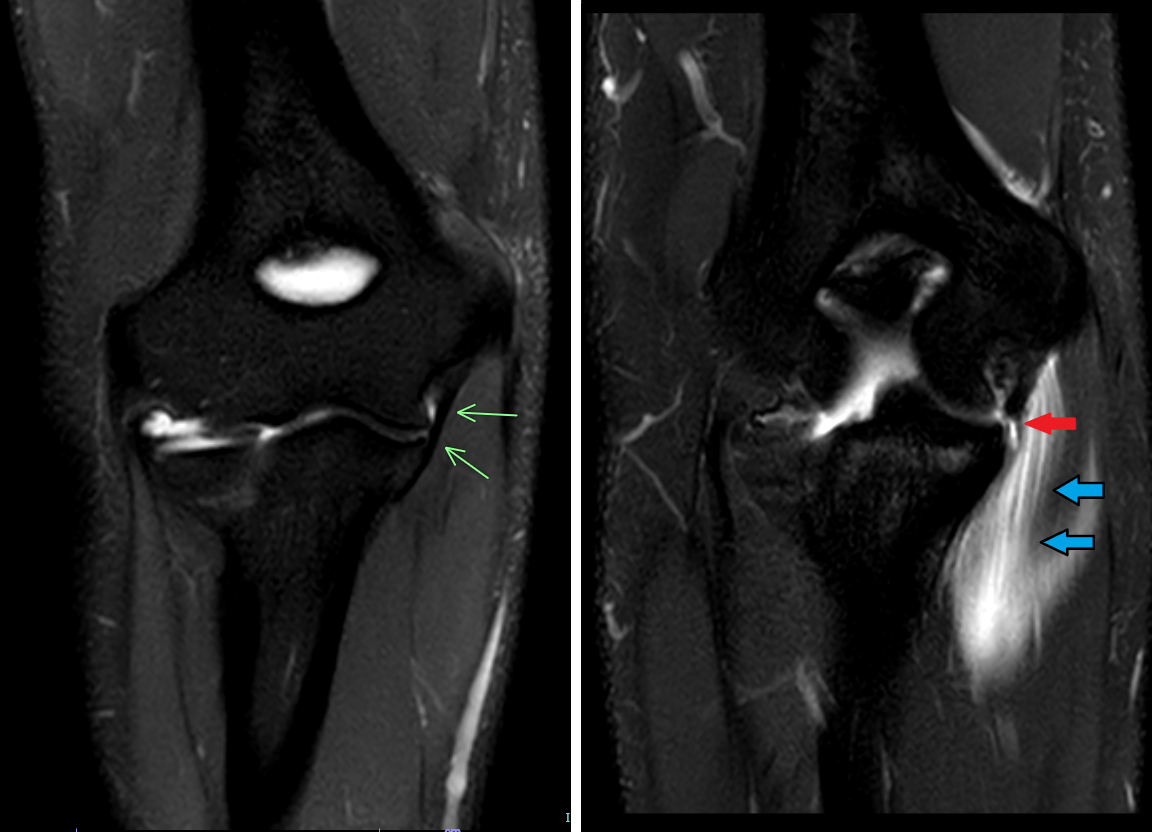

"Check out this little black line here," Misra says. "That's the ligament. That's the UCL. That's the one everybody cares about."

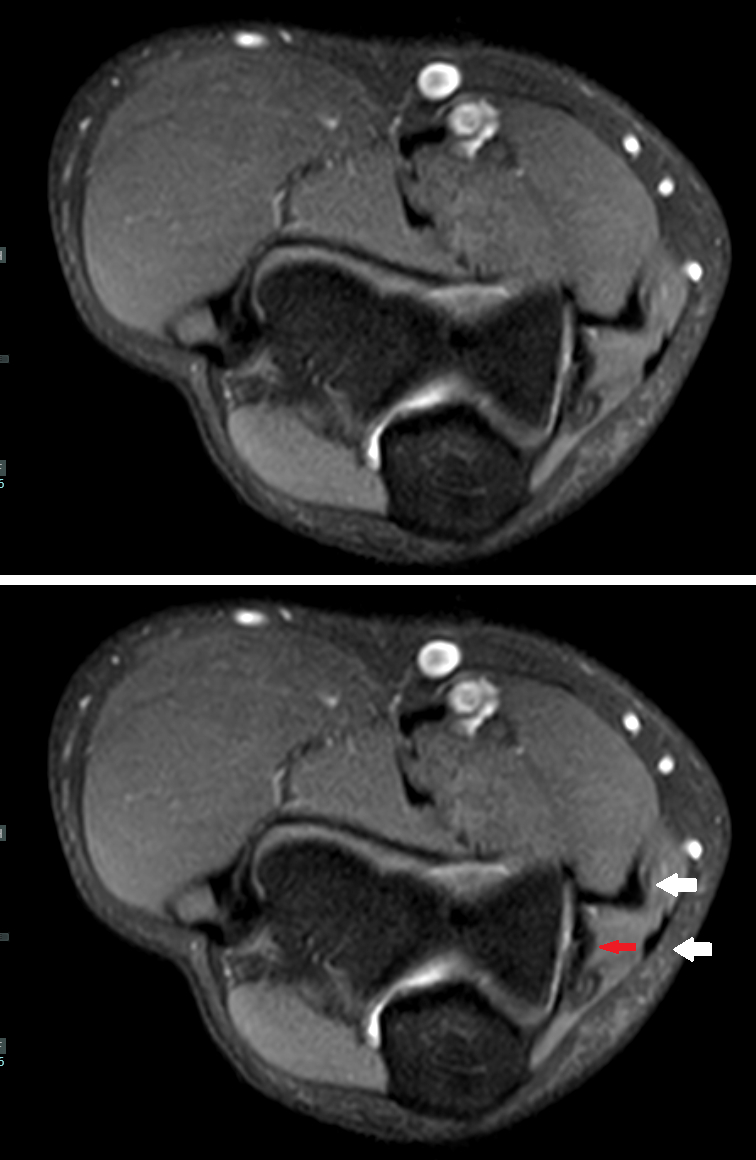

On the screen, my UCL appears as a sliver of black between other structures that appear in grays and whites.

A solid black band is good. It means the ligament is intact. It appears black because the MRI machine doesn't actually capture signals from ligaments or tendons; rather, it captures what is around them: soft tissue and fluid, which contain the water the MRI magnetizes.

So, a perfectly intact ligament is a bit of a paradox on an MRI: the absence of anything is a good thing.

If it's torn, or completely torn, there will be slices or patches of white cutting through or obscuring the ligament. Swelling around the ligament can make diagnosing an issue difficult.

"Sometimes it's not just the ligament itself that is swollen, it is everything outside of it," Misra says. "And then in terms of what we are looking for, it depends. If it's just sprained, instead of it being just a nice black line, maybe it will be thicker, so you cannot really tell where the margins are any more. Then there will be edema in it."

Misra adds: "Edema is water, so there will be higher, brighter signal with it. 'Oh look, it's thick and bright, but it's not torn. We're going to call it a sprain.'"

On the monitor, Misra isn't examining only one image; he's actually going through images captured at three different angles. The cross sections are of my interior elbow at north-south, east-west, and diagonal angles.

"What our job is, is to be able to place together two-dimension pictures (and create) a three-dimensional space," Schafer says. "I think that's what makes the difference between a good radiologist and a not-so-good radiologist."

The other thing about the ligament: it's very small.

"It's about seven millimeters," Misra says of its widest portion, near the top of the ligament.

The UCL is conically shaped as it tapers toward the forearm. It's only three millimeters thick at its most robust point, and about two centimeters long.

That small structure is what keeps the upper arm bone (humerus) and forearm (ulna) stable, and it's what must withstand the stress of 100-plus mph arm speeds in the act of pitching.

Its size limits the detail of what can be seen.

"The way we determine resolution in radiology is the number of line pairs that we can tell are separate lines per millimeter," Misra explains. "So in a millimeter, how many lines can you fit in there and tell that they are distinctive? For MRI, that's about three lines per millimeter. What that means is we can see a fraction of a millimeter but just barely. So when you are dealing with a seven-millimeter structure, we are pushing our boundaries in resolution. Something like an X-ray offers much better resolution, like six lines per millimeter."

Of course, an X-ray can tell you a lot about the state of a bone but not much about soft tissue or ligaments. Computerized tomography, or CT scans, also produce better resolution than MRIs and capture tissue. Why not use CT scans?

"It's not good at telling the difference between structures that are of a similar composition," Misra said. "So muscle and tendon, while certainly different structures, are close enough in composition that on a CT they kind of blend together. The swelling in the muscle, which is the edema we see, doesn't show as well on a CT. But the MRI is great at telling all the differences between the different types of tissues."

While a completely torn ligament is easier to assess, determining to what degree a partially torn ligament is damaged can be challenging. The determination is the difference between electing to have Tommy John surgery or trying rest and rehab.

"A sprain is a tear, a tear is a sprain." That's the thought Carroll has pinned to his Twitter profile. How much it's torn is critical to decipher.

Carroll noted earlier that Tommy John surgery is often recommended with a tear of 25% or greater. Ligaments don't heal as well, or with as much speed, as muscle tissue, due to less blood flow. And a ligament that heals with scar tissue won't be as structurally sound.

"One of the things I think people don't understand is that UCL tears aren't huge," Carroll said.

The problem, Schafer explains, is that arriving at a percentage is highly problematic.

"You'll often have a report where it reads, 'Well, there's a tear here. It's 0.1 millimeters. It's 12% torn.' It sounds like you really know what you are talking about if you can add a whole bunch of decimal points," he said. "But I think there has to be that realization of, 'How good am I, really?' I know there's a tear here or there, but I cannot honestly tell if it's a 15% tear versus 19%. We see a lot of reports like that. 'Oh, I know exactly what this is.' When someone starts telling you that, you should be suspect.

"Another thing is recognizing our own limitations," Schafer adds.

Misra examines another angle of my UCL on the screen and estimates a measurement with help from the computer's software.

"Let's measure this guy from left to right. I am calling it 1.3-ish millimeters. So if someone is calling it a 10% tear, they are calling .13 millimeters of it torn."

It's difficult to have high confidence with such an estimate.

Guardians pitcher Triston McKenzie has been MRI'd several times in his career, always at the same facility in Arizona. He has a baseline of images, which he can access on his iPhone. He understands much of what he's seeing. He had another set taken last month following what's been diagnosed as a UCL sprain, and is currently being treated with rest.

"It is definitely different than any injury I felt in the past," McKenzie told me. "But I didn't specifically know what it was. But after looking at the MRI, it kind of matched up with everything I was feeling. Kind of gave me some comfort in feeling it made the right call (to stop throwing)."

What did he see?

"Where the whiteness is in the UCL, around it, I was able to examine it," he said. "When the doctor said, 'Where are your symptoms?' and I pointed to it, he said, 'Oh, that's here in the MRI.'"

As was the case with Miller, it can also be difficult to differentiate between injuries in the elbow, which are often related or tied together.

"The common flexor tendon sits on top of it," Misra said of the UCL. "So it's very common for folks to injure both.

"The major reason why is because your common flexor tendon, and (flexor) muscles, are the dynamic stabilizers, and your UCL is a static stabilizer. The UCL is kind of like when you take your boat and tie it to the dock. There's a rope there and that's it. The rope does its job and it sits there. The UCL connects the two bones and that's it.

"But your flexor muscles can actually flex and actually do something. But if one of them starts to fail, the other is going to get a bigger brunt of the force and it may fail. So there is interplay between the two of them."

What's clear to me: getting a perfect diagnosis - a perfect image - can be challenging.

The MRI is a remarkable tool. But recognizing its limitations is critical, Schafer says.

"In some ways, it is a victim of its own success," he adds. "What we do is magic. It's genuinely amazing I can look inside someone's elbow with no more discomfort than some rattling of a magnet. But the downside is that there is an assumption I can see everything. There is a spatial resolution we don't have. There are limitations to the technology. I can be watching the highest resolution black-and-white film, and I cannot tell you what the color of the uniforms are. It's the same sort of situation.

"There are things we just can't see."

Travis Sawchik is theScore's senior baseball writer.