Left-handed hitters describe the craft of hitting lefty pitching

There are numerous endangered species in baseball.

There's the 20-game winner. Spencer Strider leads the majors with 18. There's the .300 hitter. There are only nine qualified .300-plus hitters this season despite the shift ban. Another increasingly rare player, though discussed less often, is the platoon-immune left-handed batter.

Last year, only 53 left-handed major-league batters faced southpaw pitchers at least 100 times, tied for the lowest number of players since at least 2002. This year, there are only 45 left-handed hitters with 100 or more plate appearances against left-handers through play Tuesday. That cohort is set to decline in numbers for a fourth straight full season. There were 67 in 2013.

More and more, data drives lineup decisions and takes many left-handed hitters out of the lineups against southpaws. Right-handed batters face right-handed pitchers in the majority of their plate appearances because, of course, they are of the dominant handedness, but teams generally try to limit left-on-left exposure. On the surface, there is a good reason for this.

Over the last six seasons, there has been a 17-point wRC+ gap between left-handed hitting performance against lefties compared to right-handers but only a 10.5-point gap for right-handed hitters when facing lefty pitchers versus righties.

But there is something of a chicken-or-egg debate when it comes to platooning lefties. Is the left-handed batter data weaker because it's truly a more difficult task to face a left-handed pitcher, or is the data weak because the opportunities are so few? There is also the question of whether there are benefits for lefties in facing left-handers that create good habits that carry over against right-handed pitchers.

At the team level, there is another consideration as we near October: The last six World Series champions - and seven of the last eight - have used platoons less often than the league average. That might speak to the overall quality of hitters on those teams, or they may have made roster decisions to carry additional pitchers or a tactical specialist like a pinch-runner or third catcher. Generally, though, teams don't platoon their way to titles.

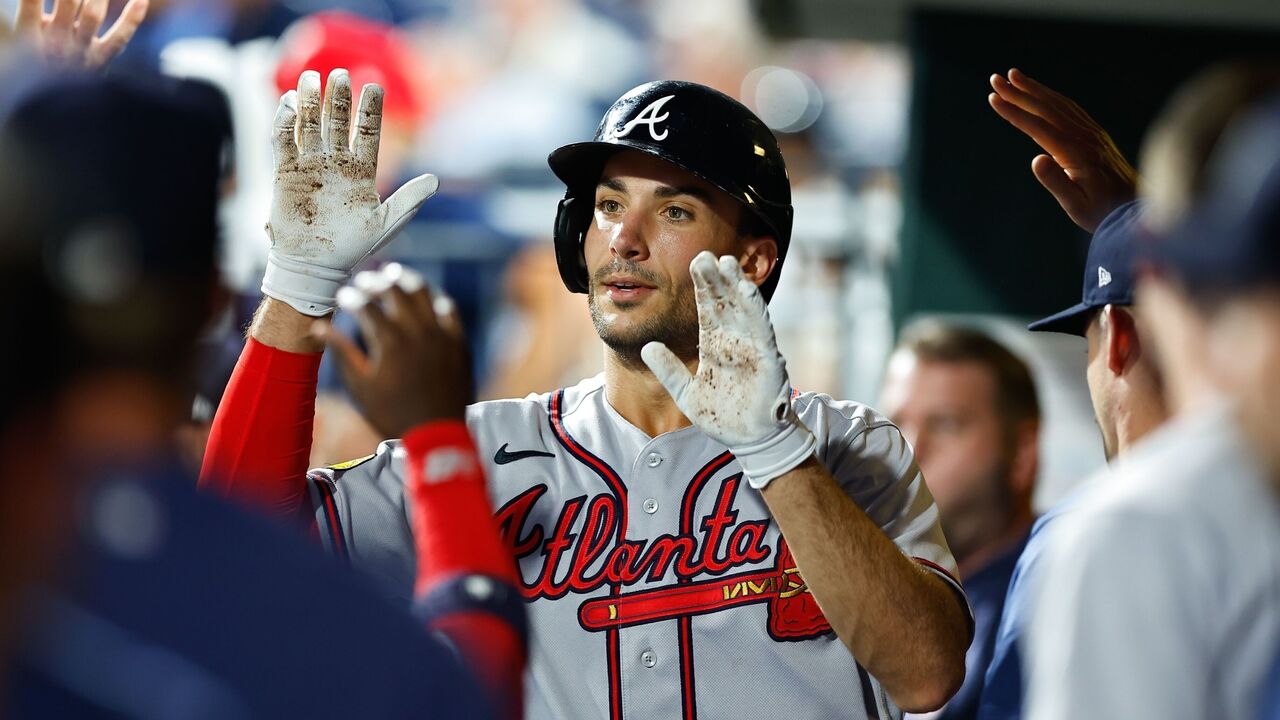

theScore spoke to three longtime star-level left-handed bats - Freddie Freeman, Matt Olson, and Charlie Blackmon - about the art of performing against lefty pitching. They are three of the 15 left-handed batters since 2010 to face left-handers at least 500 times and have a career of .780 OPS or better against them.

Do they believe fewer lefties should be platooned? What have they learned about the skill and the psychology required to step in the box at a disadvantage? What is the key to hanging in there?

No fear

To hang in against a lefty as a left-handed batter, one cannot possess a fear of the ball traveling upward of 100 mph or of a slider featuring a sweeping break. While that's true of all hitters, the left-on-left dynamic is different.

Left-handed pitchers tend to release the ball with more of a sidearm slot than righties. The average horizontal release point for left-handers in 16 seasons of pitch tracking is 24.5 inches away from the midpoint of the body versus 22.7 inches for righties, according to Statcast data. That makes the angle tougher to deal with.

"You have to be OK with (getting hit). I've had my wrist broken by a left-handed pitcher," said Freeman, referencing the damage he received from an Aaron Loup pitch in 2017. "It's a hard thing to do. You see a ball coming at you and you think, 'Well, this is either a fastball or this is a slider, so I'm going to have to hang in no matter what.'"

How did Freeman (152 wRC+ versus righties for his career compared to 120 wRC+ against lefties) develop that ability to stand in there? Perhaps his childhood explains it.

"I was always bigger than everybody else. I threw harder than everybody, and I hit the ball harder than everybody," Freeman said. "So I was always the one they were scared of. I never had that fear.

"I also had two older brothers. I think that's what helped me a lot."

Olson (career 143 wRC+ versus righties, 116 wRC+ versus lefties) said he made a mechanical adjustment courtesy of his former Oakland hitting coach Darren Bush.

"(Bush) gave me a little tip that I've kind of done throughout my career," Olson said. "If you open up (your stance) you can see the angle from the lefty a little better, and I kind of do that more so than I do against a righty. I ride (my right foot) back toward the plate. I think it helps me ride the sliders out a little better. I don't know if that's the key to that, but ever since he gave me that tip I feel a little more comfortable. I'm able to stay locked in on sliders as opposed to pulling off."

Blackmon is actually a better hitter for average in his career against lefties (.304) compared to righties (.296).

Like most batters, he rarely faced lefties as an amateur but now prepares for them by trying to replicate game-like situations in pregame practice, whether it's against a lefty batting-practice thrower or high-velocity and breaking-ball pitching machines from lefty angles.

Blackmon said the prospect of getting hit has never bothered him. "It just gives you a better on-base percentage, assuming you can stay healthy."

Crossover benefits

They were asked if there are benefits gained from those difficult left-on-left at-bats when batters then face right-handers. Olson believes there are.

"I actually enjoy facing a lefty for purposes of getting my direction the right way," Olson said. "There's a lot of times if I face a lot of righties, I get in a tendency of pulling off. Then I want to face a lefty. A lot of times when I face a lefty, I feel it helps get me centered, thinking middle of the field. Whereas with righties you start getting a little pulled off, spinny, as I would say.

"I've been pretty anti-platoon because there are times I want to face a lefty. I feel like it can get me right."

There is perhaps something to what Olson is suggesting.

theScore looked at all left-handed batter seasons from 2002-22. We compared those who received 100 or more plate appearances against lefties to those who received between 28 and 99 in a season. (The threshold of 28 plate appearances eliminates pitchers who hit in the National League before last season's adoption of the DH.)

Left-handed hitters who received 100 more plate appearances against left-handers had excellent overall numbers, producing a collective 119 wRC+ against all pitchers. Against just left-handed pitchers, their average wRC+ was 92.3.

Those left-handed batters who received fewer opportunities against left-handed pitchers averaged 97.3 wRC+ overall. Against lefties? They posted a 68.3 wRC+.

Freeman said the best way to avoid being platooned is straightforward: Be elite against right-handed pitching. "If you have success, they don't want to take you out of the lineup," he said.

Blackmon acknowledged he doesn't hit for as much power against lefties, reminding himself to keep his head still and not do "too much."

"I take some effort out of the equation," Blackmon said. "I put more of my eggs in the make-contact basket."

Chicken or egg?

Are left-handed platoon bats limited to that role because they cannot hit lefties, or are they in those roles - which can influence career earnings and longevity - because they were never given much of a chance?

"When I came up, you weren't platooned. You were given a chance," Freeman said. "Now the numbers are so (determinative), I feel bad sometimes because how do you know? How do you know that they cannot hit a lefty? But the numbers say we have a better chance to win if this happens."

Blackmon believes the game has changed so much during his career that he might not have had the same pathway today.

"I think teams are looking at players more as pieces of a puzzle more so than they used to," Blackmon said. "It used to be you had your player, that was your guy, and you committed to the person.

"Players are just a piece of the puzzle, and teams are trying to assemble the best cumulative puzzle, which is going to neglect development a lot of the time. But at the same time, this is not a development league, this is the performance league."

Olson believes numbers would be better if lefties were given more left-on-left opportunities. He contends that platoon decisions are self-fulfilling.

"If you're a platoon guy and you get 400 at-bats and 40 are against a lefty, you are not going to have good numbers just strictly based on the limited number of at-bats," Olson said. "I think sometimes those platoon stats get shifted in the way that (decision-makers) want them to be."

Olson offered another example.

"If you go look at submarine guys, if you only face them in 10 at-bats in a year, you might have really bad numbers," he said, "but does it mean you cannot hit them? So it's going to skew."

Consider the performance gap between hitters who received lots of opportunities against left-handed pitchers and those who didn't.

The lefty batters who faced left-handed pitchers most often were 25.7% worse in terms of wRC+ compared to their overall mark. But the batters who faced lefties less often were 35% less effective compared to their overall wRC+.

"Like anything in life, the more you do something, it's easier for you to go about it," Freeman said. "I feel like some guys we've called up, it's, 'I have to get a hit or I might not play against the next lefty.' … With all the computers and analytics (today), it's a different game."

We also wanted to ask a decision-maker who writes out lineup cards what he thinks of platooning versus giving a young lefty bat some runway.

Dodgers manager Dave Roberts said he tries to balance development with what is best for the lineup on a given night.

"I think giving players a runway is totally reasonable for some players," Roberts said. "I think you've seen that with the Dodgers. We've done that with (Miguel) Vargas. James (Outman) has had a lot of opportunities against left-handed pitchers. I think it's more in the vein of trying to put players in the best position at that moment.

"It's tough. You have to look at the alternatives," he said. "Playing for our club, we are trying to win every game. This is not a developmental league, not for the Dodgers."

Travis Sawchik is theScore's senior baseball writer.

HEADLINES

- Report: Astros, Cardinals, Red Sox discussed Paredes, Donovan deal

- Report: Mets agree to 1-year, $1.5M deal with Melendez

- Kershaw, Rizzo, Votto officially join NBC as MLB analysts

- Wild pitches lead Jalisco Charros to 1st Caribbean Series title

- Orioles beat Akin in arbitration, 1st win for teams this year