An offseason of discontent could lead to big changes for MLBPA

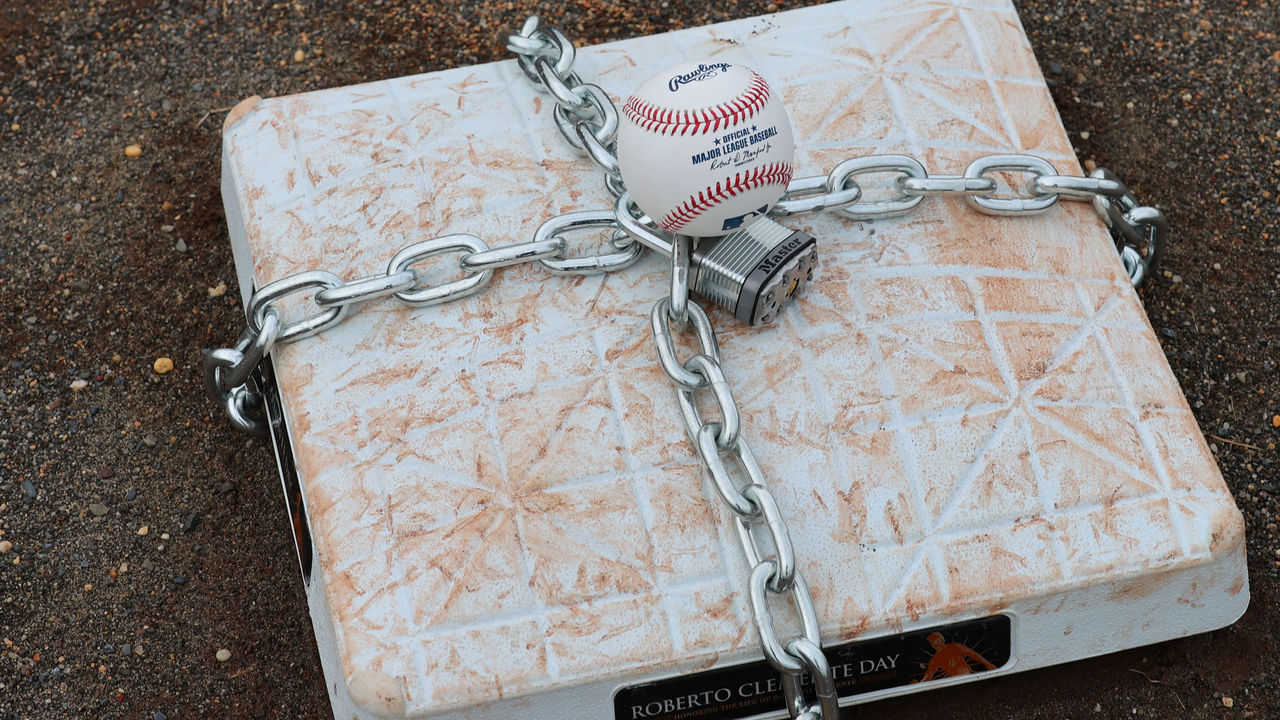

Talk of labor unrest in baseball is usually confined to the period when the players' union and the league lock horns over their next long-term collective bargaining agreement.

But labor unrest was revealed this week when several reporters, including Ken Rosenthal and Evan Drellich of The Athletic, reported that player leadership demanded the removal of executive director Tony Clark's No. 2 man, Bruce Meyer. Meyer was the lead negotiator of the last collective bargaining agreement.

Many players increasingly, it seems, don't like what they signed up for in the last cycle of talks.

Agents theScore spoke with believe issues go far beyond Meyer, though. There are questions about Clark's leadership and the outsized influence that agent Scott Boras has on the MLBPA. For some, it's as if Boras essentially runs the union.

Boras told The Athletic that the union uprising was a "coup" led by former MLBPA lawyer Harry Marino and that it should "never be done."

Marino responded by saying, "players who sought me out want a union that represents the will of the majority. Scott Boras is rich because he makes - or used to make - the richest players in the game richer. That he is running to the defense of Tony Clark and Bruce Meyer this morning is genuinely alarming."

A growing fracture was already apparent in the last collective bargaining cycle. The players' eight-man executive board voted unanimously against the deal. The board was heavily represented by top-earning veterans, five of whom are represented by Boras. The larger voting group, one representative per club, voted 26-4 to adopt the proposal, which ended the lockout.

Those votes for the deal were largely tied to the interests of the most common type of player: the younger or late-blooming athlete who's playing for team-mandated pre-arbitration pay. They wanted to play, needed to play, and they wanted to enjoy the minimum wage hike and pre-arb bonus pool money that was bargained for in the agreement. (While there was a sizable increase to the minimum salary, the league's minimum still ranks among the lowest of major North American sports.)

Union leadership and Boras himself like to espouse a philosophy of an open labor market that has no salary cap or floor, and where superstars' megadeals will be a rising tide that lifts all boats. Increasingly, teams have been able to short-circuit those trickle-down economics by relying on younger players and squeezing the veteran middle class.

The majority of players never reach arbitration before their careers end. More than 60% of major leaguers play for pre-arb salaries at or near the minimum wage. Given recent improvements in player development, the quality of young players keeps improving. No other major sport leans on minimum-salaried athletes like MLB.

In the middle are players like Adam Duvall (one year, $3 million), Tim Anderson (one year, $5 million), and Amed Rosario (one year, $1.5 million), who had to settle for modest deals below what should be their market value.

Adding to the complexity is Boras' performance this offseason. He's having perhaps his worst offseason relative to expectations. Hot-stove conversations were dominated by the fate of four of his clients - pitchers Blake Snell and Jordan Montgomery, and hitters Cody Bellinger and Matt Chapman. They were expected to be the most sought-after free agents after Shohei Ohtani. Yet they began spring training unsigned.

FanGraphs' crowdsourcing efforts projected Bellinger, Chapman, and Snell to earn a combined 15 years and $349 million this offseason. The trio instead inked deals for a combined eight years and $196 million. Montgomery remains unsigned.

"It's too bad, but it is a reflection of the current system," Greg Bouris, a sports management professor at Adelphi University and former MLBPA official, told me last month. "Unfortunately, the 0-to-3 class of players (pre-arbitration) have become more valuable than the other two classes: arbitration-eligible players and free agents.

"The historical challenge for the union has been to make sure that no class of player becomes more valuable than others. But because of advanced analytics and relatively low minimum salary, loading up on the 0-3s makes operational and budgetary sense."

The union has fought hard against a salary cap for decades, but teams have become disciplined enough to make the luxury tax into a ceiling on overall spending. There's also no salary floor, which would force teams to spend to a minimum on payroll.

Getting squeezed from all sides, it's no wonder the rank and file is voicing its anger. The next CBA talks are still a few years away, but in calls for leadership changes, players are signaling that they want a much different deal next time around.

Travis Sawchik is theScore's senior baseball writer.