A weekend in the life of the Dodgers' Japanese press corps

CINCINNATI - A few hours before first pitch, Dodgers starting pitcher Yoshinobu Yamamoto makes his way to the visiting dugout from the outfield at Great American Ball Park after completing his throwing program.

A handful of Japanese photographers standing idly near the dugout spring into action as he begins his walk.

Yamamoto is still some distance away, but they grab their long-lens cameras and drop to one knee to steady themselves. They focus on their target, and the whirring of digital shutters begins. As Yamamoto draws nearer, the photographers switch to cameras with shorter lenses. A handful of Japanese writers watch, too, standing on the crushed-brick infield warning track. They aim their smartphone cameras at Yamamoto.

In the baking, late afternoon sun, Yamamoto doesn't acknowledge the attention, slips into the dugout, and disappears down a tunnel.

Every moment Yamamoto's on the field for the Dodgers is captured through images and words - and he isn't even the main attraction for the Japanese press corps following the Dodgers throughout the season.

The North American sports fan is accustomed to two types of sportswriters: beat writers who cover individual teams, and national writers who serve as insiders or feature writers. Photographers for local media outlets or global news services typically don't travel to follow the same team but are stationed in one city or region.

But the Japanese press corps covering the Dodgers offers something quite different. This group is a traveling band, up to 25 or 30 strong on any given night, and is tasked with not covering one team or one league, but following the Japanese players working far from home.

Yamamoto's a great talent whose rookie season would be worthy of stand-alone coverage in his own right by Japanese press standards. But his teammate, Shohei Ohtani, is essentially Japan's Taylor Swift. According to some polling, he's the country's most famous person.

For North American sports media, it's unusual to be tasked with covering one or two athletes, let alone traveling around a foreign country and culture to do so.

I was curious what a day in the life (or weekend) is like for members of the Japanese press covering the Dodgers, and L.A.'s late May series in Cincinnati offered an opportunity to experience it.

The assignment to cover Japan's greatest star is a glamorous one. Ohtani's perhaps the most uniquely talented baseball player since Babe Ruth, and millions read the work produced by this press corps. Many feel grateful to have such a coveted role. But it's not an easy job.

One of their greatest challenges is that neither player is easily available, and when they do meet with reporters, they reveal little. Ohtani in particular is something of a mystery - even for the Japanese press.

During the three hours of total media availability in the visiting clubhouse during the series, Yamamoto and Ohtani were present in the clubhouse for about a combined 20 minutes.

When he played for the Angels, Ohtani spoke to reporters only after his starts as a pitcher. Initially, there was hope he'd speak more often as a Dodger since he's performing exclusively as a designated hitter this year while he rehabs an elbow injury. After all, Ohtani's the reason the Dodgers' press corps more than doubled in size this season.

That hope was short-lived.

One writer had a one-on-one conversation with Ohtani in the clubhouse during spring training in Arizona but was later informed one-on-ones weren't permitted. Instead, Ohtani would hold interview sessions with groups, where he'd address reporters in front of one of those nylon panels that feature team and advertising logos. Ad space is sold even for Ohtani's interviews.

MLB clubhouse decorum permits that when an athlete is dressed and seated at his locker, he can be approached for an interview. (There's no clubhouse access in Japan's NPB; players are interviewed outside the locker room if they're made available.) In the few minutes Ohtani was at his locker in Cincinnati, no one bothered approaching and testing the boundaries.

While Ohtani's amiable in his group press engagements and many of the writers enjoy his personality, no one believes he's all that interested in speaking to them. Ohtani even failed to appear for his media availability after being named American League MVP last season. MLB officials blamed it on factors out of Ohtani's control; perhaps he wasn't interested in fielding questions about his free agency.

So, how does the Japanese press manage to fill its content demands?

After Yamamoto walked by, as we waited by the dugout railing for Dodgers manager Dave Roberts to address the media, I asked one younger Japanese reporter - who asked to remain anonymous - about the challenges.

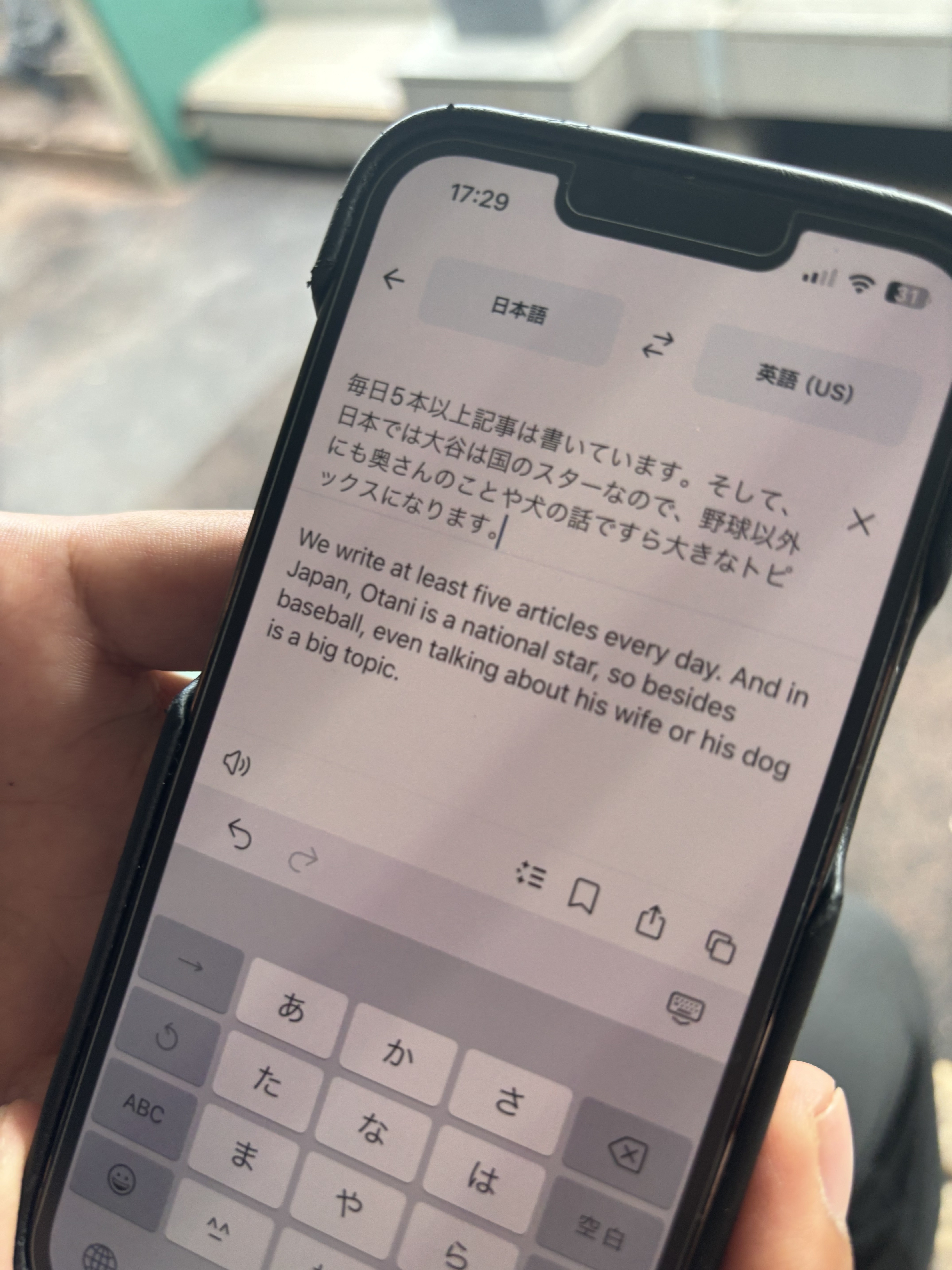

To make sure he expressed himself accurately, he spoke into a translation app on his phone and presented me his thoughts in English text:

"Japanese people want more Shohei. It is a challenge," he said. "Mr. Ohtani is a very secretive person and does not like to be too open."

The reporter said he's tasked with writing five short pieces a day - about 1,500 words total - on Ohtani during the season.

An example of a regular piece would be a short article on where Ohtani's batting in the lineup. Another is about his game performance. Other pieces could cover anything. If Ohtani posts on Instagram, that's a story. If Ohtani's dog Decoy does something, that's a story, too. Decoy's famous in Japan, too.

Any detail can be a story, to feed the appetite of Japanese readers. This was true long before Ohtani arrived.

Hideki Matsui was more accommodating during his playing days. Once, when he was with the Angels, a curious American reporter asked Matsui what the Japanese press could possibly be asking him every day.

"Sometimes they'll ask what color underwear I'm wearing," Matsui quipped.

The writer asked him what color his underwear was that day. Matsui made a quick check: "Red."

One Japanese scribe tracked and reported Matsui's batting practice home runs, recording daily how many he hit and where they landed. But that's not possible with Ohtani, whose pregame routine takes place in batting cages in the bowels of every MLB stadium.

Gaku Tashiro covered Ichiro Suzuki, Hideo Nomo, and Matsui's entire career in the majors. He became the first Japanese writer to earn 10 years of service as a member of the Baseball Writers' Association of America.

"When you cover a team, you can write about someone different every day, but we have to find another story about Matsui every day. That is the toughest part," Tashiro told the San Francisco Chronicle in 2011. "Hideki tries to help. He is the easiest Japanese player to cover."

It's not as easy today.

Journalism isn't typically a field of study at Japanese universities. The writers following the Dodgers come from a variety of backgrounds.

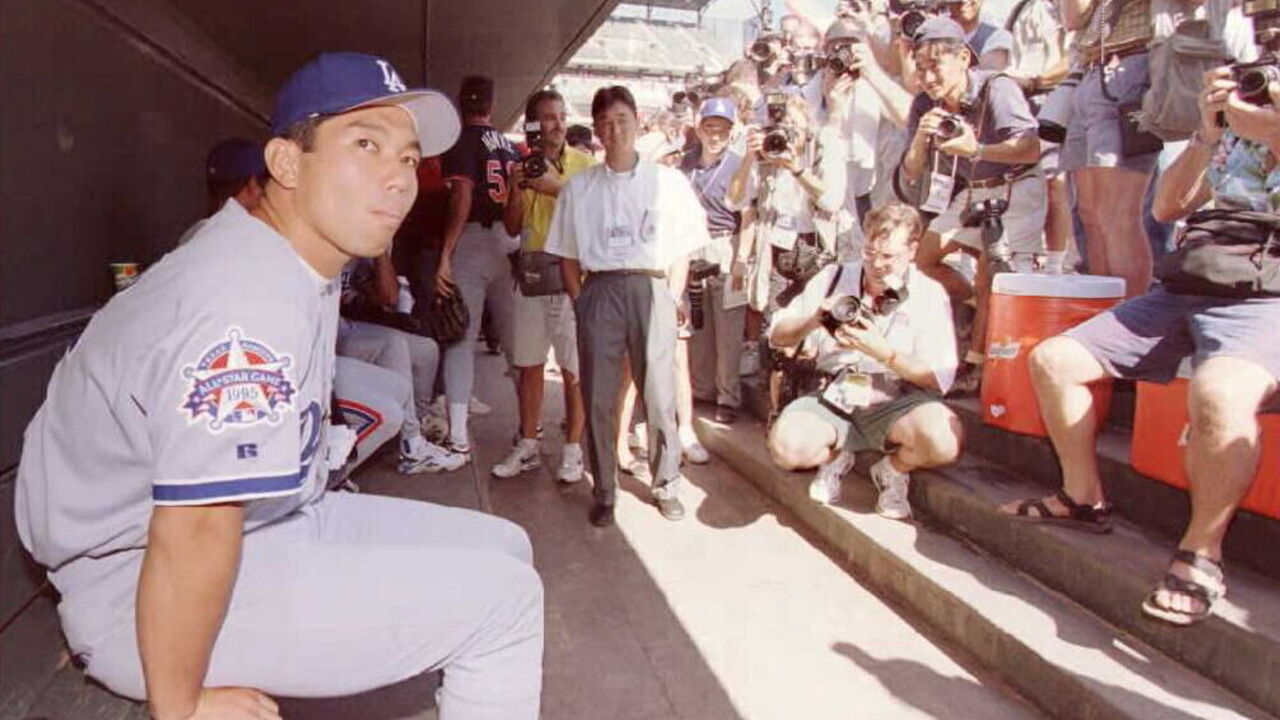

Akiyuki Shiraishi, who works for Kyodo News, a Japanese news agency akin to The Associated Press, studied law at Waseda University and played on the school's baseball team, which was the first from Japan to tour the U.S. in 1905. He always loved the game and became obsessed with it as a youngster in 1995, when Nomo began playing for the Dodgers.

After he graduated college, he decided an opportunity to cover baseball sounded more interesting than being a lawyer.

He got his start as a beat writer covering the Hokkaido Nippon-Ham Fighters, and later the Yomiuri Giants, before becoming a national writer and later taking an assignment to cover Japanese stars in the U.S.

Shiraishi was the only reporter to speak with Yamamoto or Ohtani during my time around the club. He briefly questioned Yamamoto when he was seated at his locker prior to Saturday's game.

"I asked Yoshinobu (Yamamoto) about the pitch clock," Shiraishi said. "In Japan, there is no pitch clock. (I wrote about) how he overcomes (the) pitch clock."

That's one of his stories for the day. He's usually tasked with writing three: one main story and two shorter sidebars. He estimates he produces 1,000 words daily. That's about 160,000 words a season - a lengthy non-fiction book - on the exploits of two players.

While Yamamoto's a big star in his own right, the interest in him is more like that of a supporting actor in this season-long play.

"When (Ohtani) makes a big impact, such as hitting two home runs in one game, we write two or three pages worth of articles," Naoyuki Yanagihara of Sports Nippon said.

"We only write articles about Yamamoto on the days he pitches. Yamamoto is a great pitcher, but unfortunately there aren't many articles about him. It's unfortunate that he's on the same team as Ohtani. However, I hear that Yamamoto feels comfortable in this environment where there is no focus on him."

Shiraishi said one thing that helps his ability to produce content is that the Dodgers have earned national interest in Japan.

"Last week, I spoke with a Japanese fan (in San Francisco)," Shiraishi said. "She told me she became interested in Mookie Betts and Freddie Freeman. She became interested in the other players. Almost all of the (Dodgers) games are on TV (in Japan)."

Shiraishi's started to write about Ohtani's and Yamamoto's Dodgers teammates, including their perspectives on the Japanese stars. He said the challenging aspect of branching out is the language barrier, but it helped him learn English.

Another issue is that because the media contingent following the Dodgers is more than double in size compared to last season, fewer L.A. players make themselves available pregame when reporters are in the clubhouse.

The visiting clubhouse is usually better for player access because there are fewer rooms where players can hide, and the traveling press contingent is typically smaller than for home games - especially as media travel budgets have been slashed in recent years.

But even without the full complement of Japanese press on this trip to Cincinnati (many waited instead to travel with the team to New York the following week), the clubhouse is vacant.

Life on the baseball beat is largely about waiting. That's especially the case here. On this day, there would be no Ohtani or Yamamoto pregame availability.

After Roberts' pregame session ends, the group makes its way to the elevator to the press box. It'll be another couple of hours before they see Ohtani for the first time when he steps into the batter's box.

In the first inning, when Ohtani arrives at the plate, eyes lift from screens and phones - from booking future flights and hotels, and scrolling social media - to fix attention on him.

Junko Ichimura is one of the most experienced writers on the beat. Her father loved baseball and she watched Yomiuri Giants games with him as a child. They followed the exploits of Sadaharu Oh, who hit 868 career home runs, tops all time in pro baseball. The Tokyo-area Giants weren't their local NPB team - her family lived near Kyoto, six hours away - but they were the only team whose games were regularly televised.

She worked for a large newspaper chain after graduating from university. In the early 1990s, the company was looking for a female reporter to cover the NPB and she jumped at the opportunity.

"I had a chance to cover (the Giants) when (Oh) was the manager," she said. "I took a picture (with Oh). My dad was so happy. He was never too happy with me, but he was so happy (with the photo)."

In 1996, Ichimura was offered an assignment to cover Nomo in his second season in North America. It was the biggest sports story in Japan. While Nomo wasn't the first Japanese man to play in the majors - Masanori Murakami pitched for the Mets in the mid-1960s - Nomo was the modern trailblazer for NPB stars who followed.

"I was rooting (for Nomo)," Ichimura said. "I had a mission. I need to report this. What is happening, going on every single day? How the American audience is so excited."

Nearly 30 years later, Ichimura remains in the U.S. as an MLB correspondent. She lives in Boston with her husband and covers the Dodgers when they're east of the Mississippi. When they're back west, another writer at the newspaper leads coverage. She then turns her attention to other Japanese players. There are other writers like her, tasked with reporting on other Japanese players in the majors. During Friday night's game in Cincinnati, one writer watches Kenta Maeda's start for the Tigers.

Ohtani's the biggest story for Ichimura since Nomo, but the industry is much different today.

Newspapers were still king in the mid-1990s. So were their deadlines. Filing stories was more challenging, and involved scrambling postgame to find or share phone lines for dial-up internet service. There was no social media, no smartphones. The web was in its infancy. Millions read her work in newsprint.

"You wake up in the morning in Japan and people see (your stories)," she said. "We really had to write. That was a different time."

One of the workarounds she learned over years covering stars who rarely speak: go to the opposing clubhouse and report its perspective.

On Sunday morning, the final day of the Cincinnati series, she took advantage of the Reds' pregame clubhouse time and spoke with pitcher Hunter Greene about what it's like to face Ohtani.

"He said really good things," she recalled. "He said it was like a chess match with Shohei."

Kotaro Ohashi captures images for Kyodo News. Some 50 million combined readers of various media outlets see his images. He was one of the photographers capturing shots of Yamamoto before Friday's game.

During the game, Ohashi's in the camera well next to the Dodgers dugout. He estimates he takes as many as 3,000 photos each game, and then edits those down to between 50 and 70 to send to the agency's clients.

"You have to have a sense for which play, which moment is most important for the day," he said. "I could have a great picture of Shohei, but if he doesn't have any hits, it doesn't work. Maybe then I need to take a picture of Shohei in the dugout with a sad face. What is the news that day, that moment?"

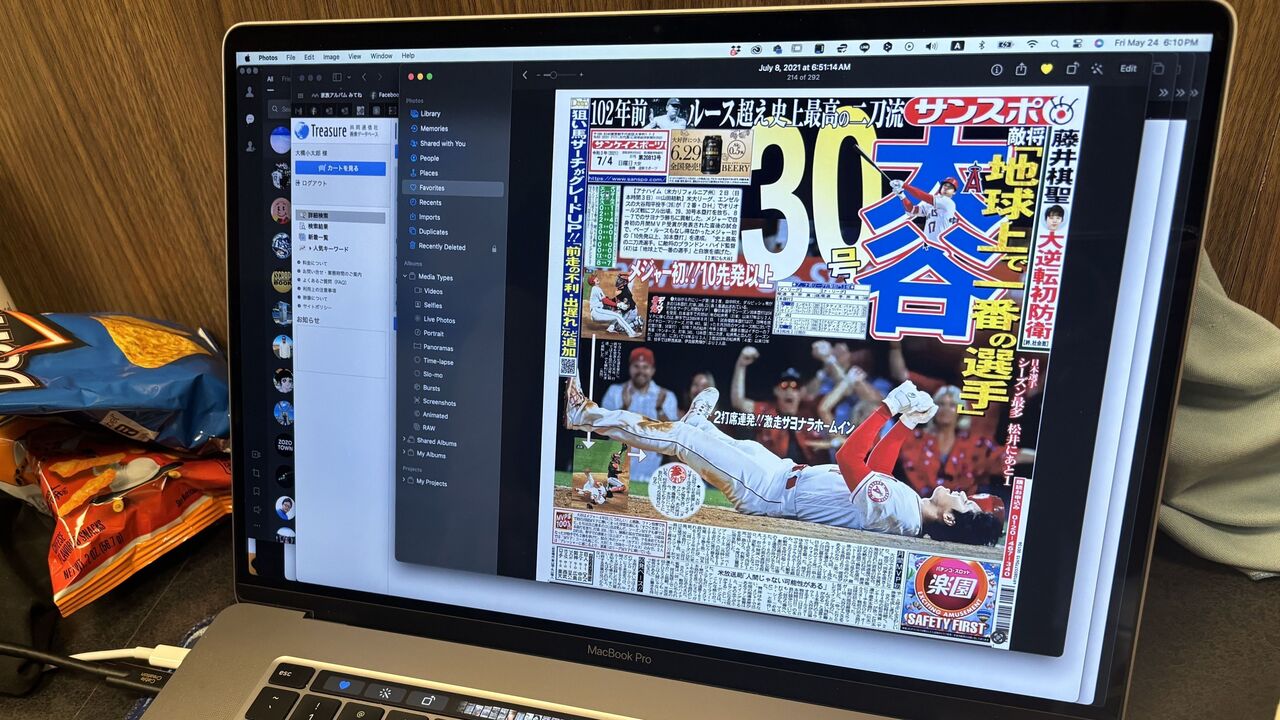

In the press box before Saturday's game, seated along a row of photographer workstations, I ask him which images he's most proud of. He begins searching through his personal archive on his laptop.

He opens one: it's a tabloid's front cover featuring an image he captured of Ohtani with the Angels. In the photo, Ohtani's laying on his back near home plate after a collision with a catcher in an 8-7 walk-off win on July 2, 2021. His fists are raised triumphantly in the air.

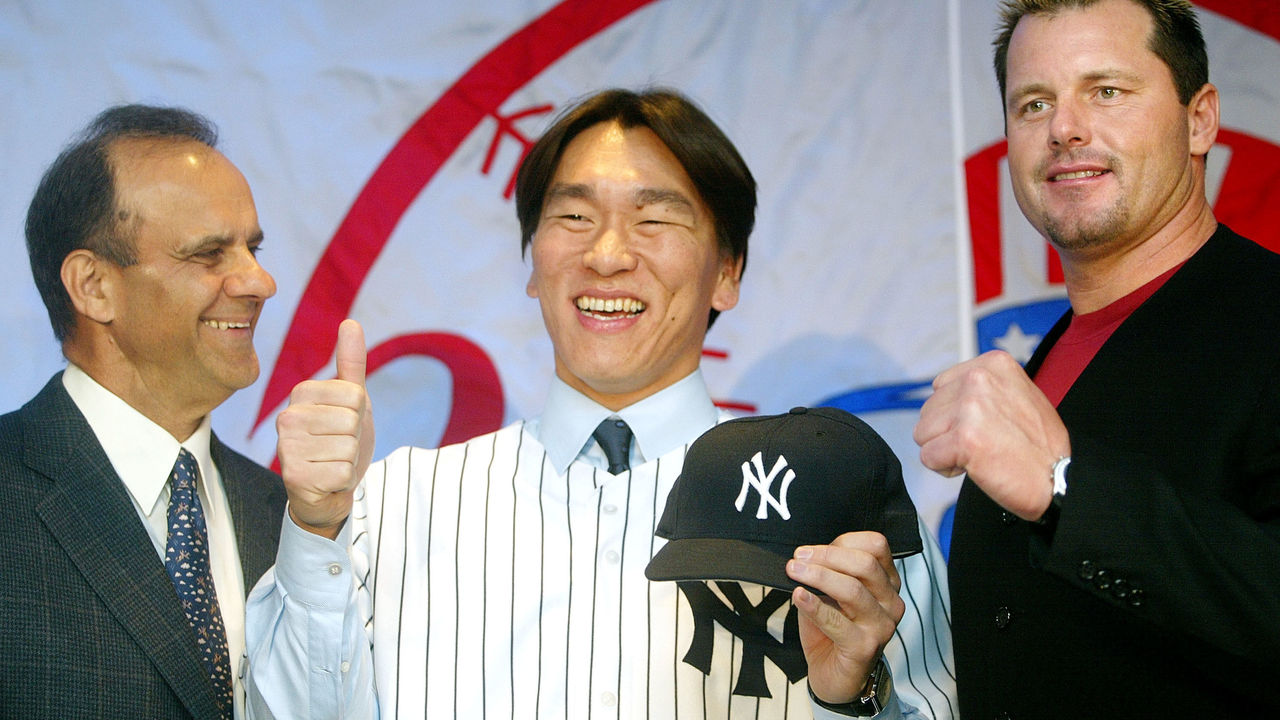

Ohashi came to the States in 2007 and was on the Matsui beat when the slugger was with the Yankees.

He recalled Matsui would occasionally dine with the Japanese press, who respected his wishes of keeping his personal life private. In Japan, there's great interest in ballplayers' private lives.

Ohtani doesn't interact with the press outside of the ballpark. When Ohtani announced on Instagram in February that he was married, and later shared a picture of his wife in March, the news nearly broke Japan's internet.

Shohei Ohtani and Yoshinobu Yamamoto are ready for #SeoulSeries! 🇰🇷

— MLB (@MLB) March 14, 2024

(via shoheiohtani/IG) pic.twitter.com/QESxA7SoKm

"We ourselves try not to ask too much about (Ohtani's) private life, but Japanese fans demand it," said the younger writer who asked to remain anonymous.

Matsui also took time to learn the name of every reporter on the Yankees beat when he arrived in New York. He knew the photographers, too.

"There were reporters in New York who covered Derek Jeter and Jorge Posada every day and those guys didn't know their names, but Hideki did," Tashiro said in 2011.

There's more separation today, but Ohashi says he prefers it.

"I have to have a little distance, because (there's) so much emotion," he said. "I must take pictures, good or bad. The bad moments, too."

The betting scandal involving Ohtani's former interpreter, Ippei Mizuhara, added a layer of awkwardness earlier this season. It was front-page news in Japan.

"Ippie was kind of famous in Japan," Ohashi said. "Everyone had a favorable opinion of him."

Beyond the challenges of covering a couple of reticent superstars, the traveling Japanese media also must contend with being in a foreign country and navigating its culture.

When Ichimura first came to the States in 1996, there was no GPS, no smartphones - BlackBerry debuted in 1999 - and Google was still just an idea in the minds of a couple of Stanford students.

The first thing she did every road trip: find a kiosk in the airport that had city maps showing where key landmarks were, like the ballpark.

Technology advances made the transition easier for those on the beat. But technology shortcuts don't exist for everything.

Ichimura had to learn to drive on the opposite side of the road from Japan. Driving was a challenge for many - especially Toyko natives on the beat, accustomed to using subways and trains. Rental cars are required for spring training and some in-season trips, too.

The food is less than ideal, too. "American food is not as tasty as Japanese food," Yanagihara said.

I asked the young writer what he misses most about being away from Japan. "White rice," he said.

He did try the polarizing local Cincinnati delicacy on the trip, Skyline Chili, which features chili and shredded cheddar cheese poured atop spaghetti.

"I ate Skyline Chili," he said. "I liked it."

The language barrier is a challenge, from ordering meals to interacting with North American ballplayers. The writers have varying levels of fluency.

There's also the family element. Some have their loved ones with them, like Ohashi, but some are away from their spouses and kids during the season.

For Yanagihara, he's away from his wife and 2-year-old for much of the season. His daughter's too young for the travel, and the weakness of the yen against the dollar makes the cost prohibitive. He video calls them every day, usually in the evening, when it's morning back in Japan.

Some of the younger reporters are single and enjoy the travel, but it can grow tiring living out of hotels and Airbnbs for more than half a year.

The reporters are only as rooted as the players they cover. What if the player they cover elects to move via free agency?

Shiraishi, who lives in Irvine, California, said he was confident Ohtani would sign with the Dodgers, but admitted there was some uneasiness on the day a private plane that Ohtani was reportedly aboard was tracked to its destination in Toronto. The Ohtani press corps was relieved when a Canadian businessman stepped off the plane.

In all, the positives outweigh the inconveniences for many on the beat, who want to tell this story.

Shiraishi said he feels fortunate to be in his position. He generally enjoys traveling, too, and goes sightseeing during his trips.

Earlier Saturday morning, he crossed the Roebling Bridge over the Ohio River. He wanted to reach Kentucky by foot. Another state checked off the list.

Later this year, the reporters' U.S. assignments will end. After a long season of countless hotels, airports, rental cars, and strange meals, many will travel to one final destination for the winter: Japan.

Eriko Takehama, a young reporter with Sankei Sports, said that even when she returns home, she can't get away from Ohtani.

Takehama sees Ohtani's likeness when she arrives at Tokyo's Narita International Airport, adorning ads for a Japanese airline. She'll see his face at local shopping malls, too, in seemingly unlikely spots like the cosmetic aisle, promoting a line of skin-care products.

They chronicle the greatest show in baseball. Even when they're off duty, they can't escape it. Like any great story, it envelopes you.

Travis Sawchik is theScore's senior baseball writer