How generous, or cheap, is your favorite MLB team's owner?

This is one of the most talent-laden World Series matchups in recent history.

The New York Yankees and Los Angeles Dodgers were the No. 1 seeds in their respective leagues, the first time top seeds have met in the championship round, in a full season, since 2017. The rosters are loaded with future Hall of Famers, perhaps as many as seven.

And that talent is expensive.

The Dodgers and Yankees were two of three clubs to spend more than $300 million on player payroll this season. (The New York Mets were the other.)

These payrolls have stirred debate. For some, this World Series underscores how imbalanced the financial playing field remains even with revenue sharing increasing over the years. For many fans of small- and mid-market teams, it remains an unfair game.

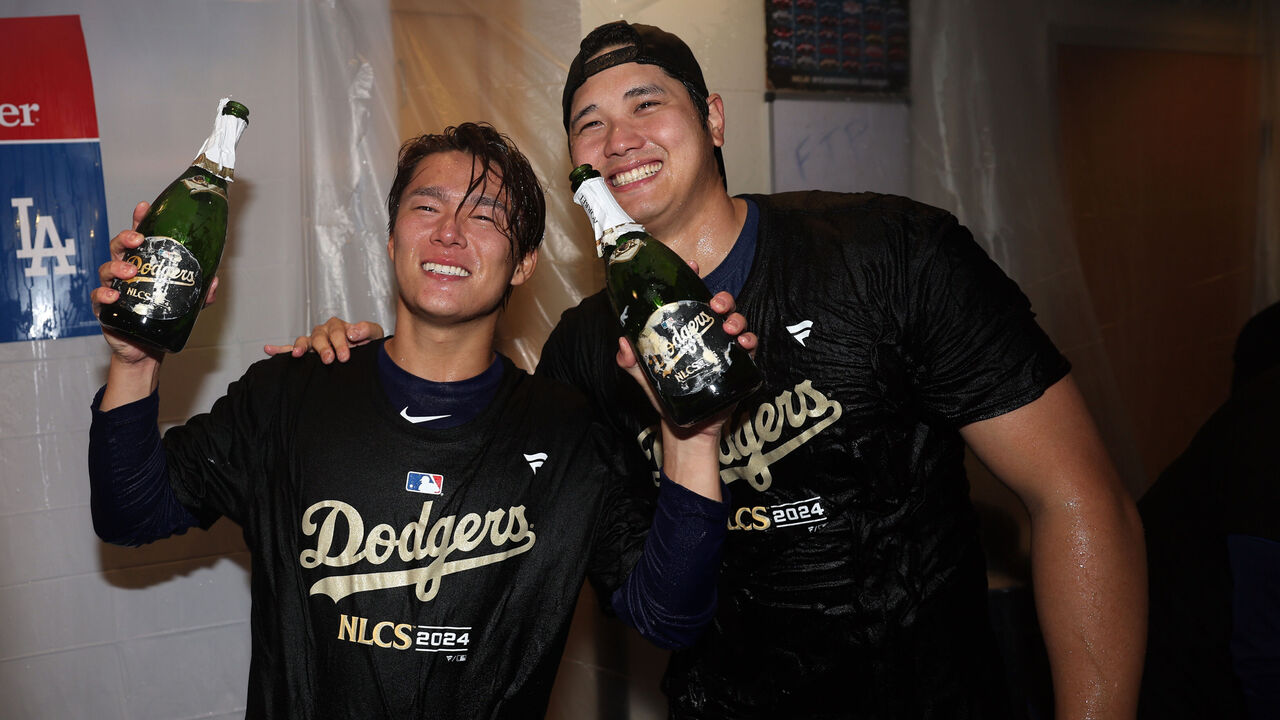

Recall back in January when the Dodgers had spent more on two free agents (Shohei Ohtani and Yoshinobu Yamamoto) than the rest of MLB combined: $1.07 billion to $1.06 billion.

In the Yankees' case, only six players on their 26-man roster are homegrown, the 25th-lowest share in MLB.

While expanded playoffs often drive parity and create chaos in a sport that requires large samples to determine true talent, the three clubs with the most regular-season wins over the last decade are the Dodgers, Yankees, and Houston Astros. Over the long haul, money does buy happiness. And it is local revenue that largely separates the haves from the have-nots.

The counterargument is that more owners should spend to be competitive. Ownership groups are very rich. Every owner could find a way to pay more for talented free agents if motivated to do so. Fans of the Dodgers and Yankees say it's not their fault rival owners do not spend more. Some owners do seem more interested in collecting revenue-sharing checks than competing.

So, are the Yankees and Dodgers ownerships generous while much of the rest of the sport is too cheap?

Comparing revenue to payroll, which owners are Scrooge-like? Some of what we found might surprise you.

To answer this question, theScore employed Sportico's team revenues for 2023, the most recently completed year, to understand clubs' cash-generating capability.

Sportico says some, but not all, of its revenue data has been verified. At the very least, it puts us in the ballpark of understanding how much direct baseball revenues are created by clubs.

We then used 2024 player payroll data from Spotrac, including estimated luxury-tax payments, and compared the figures. Front offices sign most player contracts with only projections of revenue, so even if this isn't a perfect calculation to use prior revenue against current payroll, again, it gets us in the ballpark.

There are other costs associated with owning a team, of course, but by isolating player payroll versus team revenues, we can understand the commitment level of ownership groups.

So, which ownership group has the most money left over after its player payroll and luxury-tax payments? The New York Yankees.

The Yankees have a $344-million gap between their 2023 revenue and their 2024 player payroll. They seemingly have much more room to add payroll but do not, likely in part because luxury-tax penalties provide an incentive to spend less.

New York can pay Juan Soto this offseason and still profit.

According to Sportico's data, the Yankees' revenues ($720 million) are 2.44 times greater than the 24th-ranked Cleveland Guardians ($295 million), whom they defeated in the ALCS.

As wild as it sounds, the Yankees are relatively frugal. By percentage of payroll to revenue, they rank 12th.

The most fan-friendly ownership group: Across town, the New York Mets are an extreme outlier.

Mets owner Steve Cohen's 2024 payroll bill is $9.2 million greater than the team's most recent full-year revenues. The Mets are willing to spend at a deficit like no other club. Cohen is the anti-Scrooge.

Consider that the gap between the Mets and the next most generous teams in terms of revenue minus payroll - Arizona, Kansas City, Colorado, Toronto, and Minnesota - is more than $100 million. The second-ranked Dodgers' percentage of payroll to revenue is 35 percentage points lower than the Mets'.

The MLB average for player payroll, including the luxury tax, stood at $203 million, according to Spotrac. The average gap between last year's revenues and this year's payrolls was $191 million.

Without knowing the associated costs of running a baseball team - debt payments, stadium costs, and other employee expenses - this still suggests that many owners could spend more to be competitive. It also shows how the beefed-up luxury tax is a drag on large-market teams' spending.

For a hint at teams' associated costs, we can look at the financial data for the publicly traded Atlanta Braves, owned by Liberty Media.

(The Toronto Blue Jays are also owned by a public company, Rogers, but the club's individual expenditures are not broken down in the same detail.)

In the Braves' most recent quarterly report, the club reported modest 4.7% revenue growth year over year, but a negative profit margin.

Despite having the fifth-greatest gap between revenue and payroll and the sixth-largest percentage of revenue spent on players, the Braves claim costs are eating at their profit.

theScore spoke with Bretton Fund portfolio manager Stephen Dodson in 2022 to understand why Wall Street was not more enamored with owning pro sports teams. After all, it seems that teams would be cash cows given the price of tickets and concessions. However, the margins associated with owning a pro sports business are not great relative to many other businesses.

"A sports team is almost always worth more to a very rich person than it is to a company who only cares about its cash flows," Dodson said.

For context, while the Braves claim a negative net margin in their most recent quarterly report, chipmaker Nvidia's net profit margin was 55% for its last quarter. Tech giants like Alphabet (28%) and Apple (25%) are also far more lucrative businesses, according to financial statements.

As Dodson’s co-manager Raphael de Balmann said in 2022: "Sports teams are a bit of a vanity asset, like owning a Picasso, and the highest bidder is going to be a very rich person who wants to own the team, so they (can) call themselves an owner of a sports team."

And like a piece of fine art, most of the value of a sports franchise comes from the appreciation of the asset. (The other great benefit is that depreciation of assets related to owning a team can work as a giant tax shield.)

Yes, it would be great for fans if more billionaire owners were willing to spend on the franchises they own, even operating at a loss in order to win. Winning is bound to increase revenue.

However, a large portion of their cash streams, namely local and national media dollars, are fixed over extended periods.

And there is a scarcity problem.

One is there are only so many billionaires. There are 759 in the United States, and of those, how many are interested in owning a sports franchise? How many of them would be willing to operate like Cohen?

Even though someone might have a net worth of, say, $4 billion, most of that wealth is likely tied to owning a company or other nonliquid assets. There isn't $4 billion sitting in a checking account.

Until there is a mechanism forcing more payroll parity (hello, salary floor), talent will go where the money is. The have-nots will need to build from within and hope for playoff chaos.

All of this is going to get more complicated as several teams work through the loss of their cable deals with the bankrupt Diamond Sports, which operated the former Bally Sports regional networks. The Dodgers, for instance, still have a lucrative local cable TV deal, while many other clubs will see a major reduction in broadcast revenue until they can work out new contracts.

Travis Sawchik is theScore's senior baseball writer.