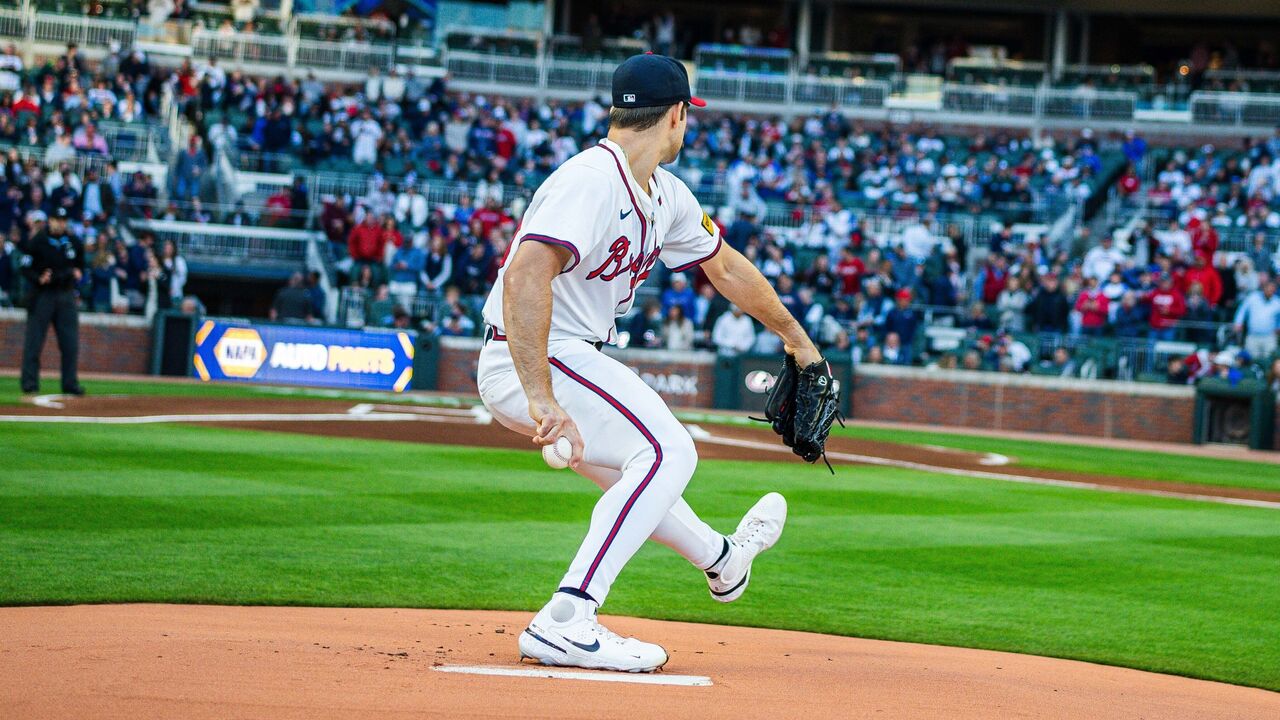

Strider aims to redefine what's possible after 2nd elbow surgery

NORTH PORT, Fla. - As Spencer Strider waited in pre-op for his second major elbow operation last April - five years and six weeks after his first - he wasn't entirely sure what surgeons would do to the inside of his right arm.

The Atlanta Braves pitcher felt discomfort last spring, so he consulted with several surgeons and radiologists about the best path forward regarding his damaged ulnar collateral ligament.

Several recommended a second Tommy John surgery without hesitation.

But Dr. Keith Meister didn't have a firm answer. Imaging science isn't infallible.

Meister gave Strider a menu of options he might pursue for the surgery, but he wouldn't commit to a specific plan until he could examine the ligament with his own eyes. At that point, Strider would already be under anesthesia, so he had to agree in advance to multiple courses of action.

"I liked that uncertain perspective (Meister) had," Strider said. "He said, 'I cannot tell you what the best thing is until I see it.' And that patience, and just like zoomed-out perspective, made a lot of sense to me."

Strider wanted to avoid a second full Tommy John knowing the track record.

About 90% of pitchers return to the mound after their first Tommy John surgery, but the outlook is less positive for repeat customers. According to Jon Roegele's database, 162 players have undergone a second TJ, and only 105 have returned to date (64.8%).

MLB's injury study released in December revealed that only 59% of pitchers who underwent a second Tommy John surgery managed to return to their previous level of performance.

"I've already had Tommy John, which means they've already drilled tunnels in my bones, which means there is less space to do that again, which means my body has to heal again, and the last time it healed, it grew a giant bone fragment in my ligament," Strider said. "So the idea of a full reconstruction with another graft, is that a great idea? What kind of risk does that expose me to?"

Strider is ready to return this week from his second elbow procedure - although not a second Tommy John - after three rehab outings in the minors. He's one of three high-profile pitchers making a comeback this season from a second elbow procedure. Two-time Cy Young winner Jacob deGrom has already returned to action with the Texas Rangers, and Tampa Bay's Shane McClanahan is expected back soon.

Strider, deGrom, and McClanahan are no longer outliers. Second major elbow surgeries are becoming increasingly common because of the stress of pitching in the modern game. A staggering 36% of active pitchers have undergone Tommy John surgery. Of the 162 players with multiple elbow operations, 130 have occurred since 2010.

Why do the second surgeries fail so often?

Orthopedic surgeon Jeffrey Dugas says a second Tommy John surgery often changes the dynamic of how the joint functions.

"You're putting another (tendon) graft on top of an already bulky piece of tissue, and that does change how the joint responds, how it creates tension … and holds the joint stable," said Dugas of repeat ligament reconstruction. "You also have some healing issues because you've already drilled the bone and put tendon in there."

In a Tommy John operation, surgeons drill tunnels through the upper arm (humerus) and the lower arm (ulna) and thread a tendon graft - typically taken from the pitcher's forearm or knee - through the channels to reconstruct the damaged ligament and restore stability to the elbow.

Drilling a second set of holes creates new complications.

"Assuming it was done well the first time, you are drilling into the same part of the bone, so you are asking the bone to heal to the tendon in a place where the biology interface is not likely to be as good as it was the first time," Dugas said.

That makes a second repair more likely to fail.

There's little that can be done to overcome these biological limitations. Instead, pitchers need alternatives. They need medical and sports science breakthroughs for better second-surgery outcomes, which Dugas sought to provide.

As Strider's hour-long surgery began, Meister identified the issue with his elbow - something an MRI couldn't reveal. A fragment of extra bone, formed during the healing process of his first surgery, had become lodged in his UCL. This fragment had obscured the MRI images, making the damage appear more severe than it actually was.

Because the partial tear from the fragment was near the bone, Strider became a candidate for a relatively new procedure: InternalBrace surgery, a technique pioneered by Dugas.

"Tommy John fits all," Dugas said. "InternalBrace fits some."

As of last April, only 41 Division I or higher-level baseball players had undergone the InternalBrace procedure, according to Roegele's database. Despite its unfamiliarity, Strider approved the InternalBrace as an option before surgery. Beyond the specifics of his injury, he appeared to be an ideal candidate for the procedure.

After undergoing his first Tommy John surgery at Clemson, Strider delved into the science of the procedure and taught himself to become an elite performer. The logic and methodology behind the new InternalBrace surgery seemed sound to Strider. It didn't hurt that the Mariners' Bryan Woo and San Francisco 49ers quarterback Brock Purdy were notable successes.

"I defer to experts," Strider said. "I think (Meister) has seen the inside of more elbows than most."

The InternalBrace procedure represents the kind of scientific advancement Strider believes is possible, offering pitchers a better chance at a successful return following a second elbow surgery.

Its origin story dates back to the early 2010s when Dugas was working with renowned Tommy John surgeon Dr. James Andrews, who shared a disheartening thought.

"'It's a shame we have to do this big operation for this little bit of injury,'" Dugas recalled.

That made Dugas curious: Why was there only one tool (Tommy John) for a range of elbow repairs?

He came across the work of Scottish surgeon Gordon Mackay, who had used tiny anchors and a new Kevlar-like, collagen-coated tape dubbed FiberTape to help heal ankles.

Dugas believed it could work in elbows.

He contacted the company that produced the anchors and tape, Arthrex, and asked to travel to its headquarters in Naples, Florida, to test the concept on cadavers. In the lab setting, it worked. Now, Dugas had to wait for the first human case.

Dugas was looking for a patient with a UCL tear near the bone, ideally the humerus, and whose ligament tissue appeared healthy enough to be reattached without a graft.

He found one in Mark Johnson, a high school senior from Ozark, Alabama, whose trailblazing operation occurred on Aug. 8, 2013.

Injuries near the bone have a better chance of healing due to the bone's rich blood supply, which ligaments lack. For example, a tear in the middle of the UCL often can't heal on its own because of the ligament's limited blood flow. The hope was that scar tissue from the micro-drilling of Johnson's humerus would adhere to his reattached torn ligament, allowing it to heal without a tendon graft. FiberTape and tiny 3.5mm anchors embedded in his humerus and ulna held in place and supported the ligament.

Unlike a full Tommy John, which requires a tendon graft to reconstruct the ligament, the InternalBrace procedure is designed to avoid grafts, though some hybrid surgeries involve both. Also important: the surgery doesn't need to drill new tunnels completely through the bone.

"Tendons and ligaments are similar, but they are not identical," Dugas said. "When you place a tendon graft onto something, it has to heal onto that something, and then it has to undergo a process of ligamentization, which basically means the fibers of that graft have to orient themselves and become ligament-like. And that's the process that takes 12 months.

"(Conversely) when you are just putting ligament back where it came from, it doesn't have to undergo that process. It's already ligament. It just has to stick."

The procedure promises a quicker return.

Five and a half months after Johnson underwent the first InternalBrace elbow procedure, his athletic trainers sent Dugas a video of him throwing at full effort off the mound. Dugas was alarmed, but Johnson was adamant he was ready. Johnson went on to have a college career.

Seth Maness became the first pro pitcher to return to the majors following the surgery in 2017, eight months and 27 days after his operation.

On average, players return to action in 11.3 months after an InternalBrace procedure. Since 2016, Tommy John recipients average 18.8 months.

Strider probably could have returned earlier this season. He was throwing bullpens 10 months after his surgery. He dominated in his rehab outings.

Dugas said he and his team are soon set to publish a paper showing that pitchers who undergo an InternalBrace procedure after a previous Tommy John surgery experience better results than those who have a second Tommy John.

According to Dugas' research, only 42% of pitchers who have a second Tommy John surgery return to pitch at least 10 games at the MLB level.

"I expect we will be able to show that returning from a second injury is considerably better now," Dugas said.

McClanahan had a full Tommy John surgery and an InternalBrace installed, as did deGrom.

"Every circumstance is different. Every person is unique," McClanahan said.

Even with the second surgery, McClanahan isn't interested in slowing down despite MLB's interest in reducing velocity. He doesn't see any incentive to throw with less force. He hit 99 mph this spring.

"Batters are getting stronger," he said. "Pitchers are pitching harder to combat that."

Like Strider, McClanahan believes it's on the medical and sports science establishments to push the game forward. That evolution may already be underway with new procedures like Dr. Christopher Ahmad's "TJ3," a hybrid surgery combining traditional Tommy John ligament repair and reconstruction with an InternalBrace.

Still, surgery is only the beginning of the long road back to the mound.

While it might seem like pro baseball is overwhelmed with data, Strider believes we need more.

MLB's December injury report identified increased pitching velocity as the primary driver of arm injuries and that the plague would continue unless something changed. But pitchers aren't going to dial back their velocity; there's no incentive to do so. Instead, Strider said, the change has to come from somewhere else.

"I think different parts of the baseball industry have moved at different speeds," he said. "For instance, we have learned way faster how to improve velocity, improve mechanics, improve strength as it relates to rotational force output, which is another way to say throwing. But, for instance, we have not as quickly learned how to manage workloads, starting at the amateur level."

Surgical advancements offer a path to recovery, but the best solution is preventing injuries in the first place.

To fuel his own development, Strider has been collecting loads of data on himself.

Even before his injury, he began working with Maven Baseball Lab in Atlanta. Strider figured the more information he had, the better his chances of staying off the operating table. And if another injury did occur, the database would give him a better road map to follow during rehab.

"I relied on (Maven) heavily," Strider said. "I've built a database with them over the last few years, throwing in the offseason, accumulating data, with the intention of, 'At some point I am going to need this, I am going to need to understand why I was moving this way when I was doing well.'

"That's another aspect of the injury conversation that the industry is not thinking about. When guys are moving well, when we have someone who has demonstrated elite health and the ability to recover, we need to understand as best we can what their workload is like, what their movement pattern is like."

Even during his excellent 2023 season, Strider, an analytical reasoner, believed he was too subjective in thinking about how he was feeling and recovering. He wanted a more objective, data-driven approach to guide his routine and decision-making.

"(The Maven database) allowed me to disassociate from my subjective opinion of how I'm moving," he said. "We are wired to look for positivity. It's easy to look at a video of yourself throwing and say, 'Yeah, it looks good,' because we crave that affirmation. Rather than, 'Nope, that's still not right. That's not where it needs to be.' The data and technology … regardless of how I feel and what someone thinks, it's not conjecture. That change was instrumental."

In addition to in-game data from Statcast and the insights from high-speed cameras and spin-rate tracking tools used in the bullpen, Strider now wears a Pulse arm sleeve to monitor every throw he makes. The device helps track his workload and measures the peak forces he's placing on his arm, giving him a clearer picture of the physical demands he's facing.

"We should be putting that on everybody," Strider said. "Let's figure out how many throws you are making. How much stress are you putting on your arm between starts? Let's start to find everybody's optimal workload base."

Through this second recovery, Strider hopes not only to improve but to challenge conventional thinking about what is possible.

Strider wants to show MLB that a second major operation doesn't have to be the end of something but rather the beginning of a long and productive new chapter.

Travis Sawchik is theScore's senior baseball writer.