Jameson Taillon's road to recovery took him down baseball's new path

Jameson Taillon awoke in the recovery room of the Hospital for Special Surgery in New York on Aug. 14, 2019. His right arm lay propped up on a pillow and wrapped in medical gauze from his right wrist to above his elbow. He'd arrived there to have a strained flexor tendon repaired. But when Dr. David Altchek entered the room to go over the operation results, he explained he also found damage to Taillon’s right ulnar collateral ligament. Taillon learned he was now a member of the small group of pitchers to have two Tommy John surgeries.

As Taillon absorbed the news, his overriding emotion was, surprisingly, relief. He finally knew what was wrong. He'd felt pain in his throwing arm since early in spring training with the Pittsburgh Pirates. His elbow throbbed the day following starts. His bullpen sessions between appearances were low-intensity affairs in which he was unable to work on building skills due to discomfort. He just hoped to be healthy enough to make his next start.

Having now had his UCL reconstructed twice, he vowed to do something dramatic: Taillon was going to change the way he threw. All the muscle memory he'd built? All those mechanical cues he was taught and earnestly followed? He was going to discard it all and start from scratch. He was going to rebuild and rewire his delivery.

He knew the odds were against him. According to Jon Roegele’s database, of the 71 major-league pitchers to have two Tommy John surgeries, only 11 have reached 10 career wins above replacement, and only two have reached 20 career WAR: Josh Johnson (21.8), who never pitched after his second TJ, and Randy Wolf (27.2), who pitched 61 innings after his second surgery. Taillon didn’t know those exact numbers, but he knew it wasn't encouraging to be in that rare company.

Despite those odds, and despite something of a lost decade in pro baseball since being selected second overall in the 2010 draft between Bryce Harper and Manny Machado, he felt a sense of freedom in the recovery room. He was going to take whatever remained of his career into his own hands.

Even before the surgery, he was paying attention to how the game was changing. He saw training techniques and throwing motions changing at a rapid pace. He was astounded by the wealth of free, quality information available on Instagram and YouTube. He felt empowered to take control of his own training. He was particularly curious about a couple of recent success stories, Lucas Giolito and Shane Beiber, who'd shortened the distance their hands traveled in their throwing motions en route to great success.

Taillon was the opposite. He had an extended, lengthy throwing motion.

"You know what, man? I am athletic. I have the talent," Taillon recalled during a recent phone conversation with theScore while he strolled the streets of Manhattan. "Why can't I be like one of those guys? I have that within me."

He thought there had to be a better way to throw and perhaps that they'd found it. Maybe he could, too.

In 2014, Driveline Baseball was a garage start-up. The baseball training facility in suburban Seattle operated then in an attic above a gym, a spartan space complete with exposed I-beam rafters. Kyle Boddy built a home-brew biomechanics lab there, rolled out some cheap astroturf carpet, and mostly trained high school and youth pitchers. Five years later he was hired to develop minor-league pitchers for the Cincinnati Reds. It speaks to how the game can move slowly for years and then decades' worth of change seemingly happens overnight.

For Boddy, the story of modern player development is about testing every idea, crazy and conventional, and measuring the results. Boddy's described his process as inspired by the "first principles" approach of Elon Musk, who claims that the philosophy of testing every assumption is what led to SpaceX making cheaper rockets from scratch and Tesla electric cars. Boddy wasn’t so much interested in coaching pitchers as he was in engineering them. The "Moneyball" data revolution was about applying economic theories to baseball. This was different. The next data-based revolution, Boddy felt, was mastering the game’s physics: from ball flight to mechanics.

In those early years, Boddy read more than he trained. He read peer-reviewed papers on weighted-ball training and dry, dense books like Frans Bosch's "Strength Training and Coordination: An Integrative Approach" to learn about how the body worked and how to best train it. He bought and read anything that could contain an idea to explore. Several years earlier, he'd ordered a Japanese-language book by Kazushi Tezuka, a baseball instructor in Japan, but struggled to find someone who knew enough baseball and Japanese to translate it. In 2014, a Google Doc with the translated text finally arrived.

As he went through it, Boddy read about what Tezuka called the "elbow spiral" motion, or, in essence, a shorter arm path. It was a common throwing motion seen in professional pitchers in Japan, which Boddy theorized was caused by the great volume of throwing they did. In the text, Tezuka advocated for the shorter arm path, in which the initial, back-side part of the motion does not extend the arm toward second base as Taillon did; rather, it kept the arm nearer the body. It was more like how a quarterback threw.

In technical terms, the core concept married external, or outward, shoulder rotation to supination of the arm, meaning the forearm was in a forward-facing, more relaxed position. Supination is the opposite of pronation, the twisting of the forearm that forces the palm outward and thumb toward the ground. Pronation happens naturally as pitchers release the ball and follow through. But Tezuka posited there should be no pronation of the pitching arm at that early stage of the throwing motion like Taillon and many others did.

By condensing the throwing motion, it also better allowed for the proper sequencing of the delivery. If one thought about it as an engineer, one was essentially reducing unnecessary parts.

"It was like, 'Oh, wow, this is an interesting concept,'" Boddy said.

While some pitchers naturally arrived at this motion, it was the first time the concept was written in English. At the time, short arm action was thought to be risky by many coaches. The nonconformist Boddy, who never played professionally and only briefly coached a freshman baseball team, thought about how he could teach it.

He'd become a believer in the power of constraint training, which featured weighted balls. The theory behind using them is their weight forces the body to adapt and organize itself in a more efficient manner. It's a way to teach motor skills implicitly, rather than from a coach barking suggestions.

"Inherently when you put a two-pound ball in your hand and tell a guy to throw he's going to shorten his arm action naturally," Boddy said. "It's just a much more efficient way to transfer that much weight into a loaded (throwing) position. It inherently doesn't feel good to swing the arm really far away from the body. You create a lot of torque."

Boddy says to imagine extending your arm out with your hand holding a 20-pound weight. Your body would naturally want to bring the arm closer to the body to protect itself.

Driveline published an article on the elbow spiral in 2015 and released YouTube videos on training exercises related to it.

Driveline's first and most well-known major-league client, Trevor Bauer, arrived at a shorter arm motion without ever thinking about it. Boddy thought it was tied to the high volume of throwing and weighted-ball work he'd done. In the following years, the Cleveland Indians, who Bauer was then pitching for, began teaching it. As weighted-ball regimens proliferated in the game, shortened arm actions begin appearing. Cleveland was an early adopter. Shane Beiber, Zach Plesac, and Aaron Civale, all Cleveland rotation fixtures, feature a similar, short arm action.

"It's pretty surprising how extreme it's going with Cleveland, especially," said Boddy, who was briefly a consultant to the team. "It's obviously coached there, which is surprising, to see the extent of how far it has gone. You are seeing it league-wide because the best pitchers kind of throw that way. … It just gives you a chance to be on time better. It reduces slack in the arm."

While there are no peer-reviewed studies on whether it's a safer arm path, only one of Cleveland's major-league pitchers (Cody Anderson) has had Tommy John surgery since 2015, tying the Chicago Cubs for the lowest mark in the majors. (Mike Clevinger had Tommy John after being traded by Cleveland to San Diego.)

Boddy estimates half of Cincinnati's minor-league arms now have shorter-style arm paths either because of the weighted-ball programs they've been exposed to, or because they developed it on their own as amateurs as they tried to mimic major leaguers.

More pitchers were beginning to take notice. Taillon was one of them.

Taillon followed Driveline’s social media accounts. He read some of their training research and watched their YouTube videos. He followed accounts like that of former minor leaguer Robby Rowland, who creates detailed mechanical breakdowns. He found during quarantine players were sharing more ideas and workout routines than ever before.

Tallion sent Giolito a lengthy text message asking how and why he'd changed his mechanics. Giolito responded that he was trying to better connect his lower and upper halves. It transformed Giolito from a failed first-rounder to a Cy Young candidate, finishing seventh last season. (Bieber finished first.)

"I am always creeping on guys' (social media) pages and talking to guys around the league," Taillon said.

The change in arm action for Giolito from 2018 to 2019. Allows for elbow spiral and more efficient mechanics.

— Coach Hilts (@CoachHiltsAHS) July 7, 2019

For more info on this concept, read this, and there are further resources within the piece: https://t.co/2VOwA6vcrD pic.twitter.com/KX2dc66US7

Taillon loved watching Bieber's compact, connected, and fluid delivery. Taillon witnessed firsthand how quickly his former Pirates teammate Joe Musgrove had shortened his arm action over the course of one bullpen session. The evidence was mounting even before Taillon's second surgery.

Taillon read about these new pitching ideas before he felt pain again in his elbow. But he wasn't ready to make a change. After all, he had a 3.20 ERA and won 14 games in 2018.

But after his surgery, he went to the Florida Baseball Ranch in Lakeland to create a constraint-based throwing program he hoped would give him a new delivery. He was shown video of efficient throwers like Nolan Ryan and Tom Seaver and commonalities in efficient motor patterns were pointed out.

He returned to the Pirates' spring training and developmental complex in February 2019 with a plan, one he could never imagine acting upon or being approved by Pirates officials in previous years.

Taillon's lived through two eras of baseball and he's only 29.

When he first entered professional baseball, Taillon was told on the back fields and bullpens of the Pirates' spring training complex in Bradenton, Florida, to go away from the mechanics that made him the No. 2 pick. In those days, there were no weighted balls or spin-tracking Rapsodo devices found in professional bullpens. Coaches' eyes, biases, and thoughts ruled. Few thought you could train velocity then. So when Taillon hit 99 mph at Woodlands High near Houston, Texas, he went soaring up draft boards.

"If you look at my high school video, my delivery is actually pretty good," Taillon said. "I was much more sequenced, much more connected. And I threw gas. Then you get into pro ball and it's 'Well, you're 6-foot-7, you want to use your height to your advantage. Why are you dropping in your back leg like that?'"

The Pirates had a pitch-to-contact philosophy then, predicated on throwing two-seam fastballs down in the zone and ideally from high release points to create as much of a downhill angle as possible. They wanted ground balls hit into their newly implemented infield shifts. And it worked for some of their pitchers. But it was a time before Statcast, before the correlation between spin and strikeouts was measurable, before hitters began joining the fly ball revolution en masse. It was a time of an organizational, one-size-fits-all approach. Taillon listened. He respected his coaches. He's amiable. But as it turns out, he was driving down the wrong road for years.

"When I got into pro ball, it wasn't just the Pirates, weighted balls were super frowned upon. Everyone was supposed to throw the exact same way," Taillon said. "No one was allowed to long toss. Stuff like that. … I don't think baseball was in a place then for guys to make those changes."

After the 2019 season, there was a regime change in Pittsburgh. After watching Gerrit Cole, Tyler Glasnow, and Charlie Morton leave and become stars thanks in part to more individualized training and approaches, the Pirates were now shifting toward focusing on player-specific plans, too. Under new general manager Ben Cherington, the Pirates signed off on the improvement plan Taillon put together, piecing together various elements he learned and liked. New Pirates pitching coach Oscar Marin and newly promoted bullpen coach Justin Meccage supported Taillon's experiment.

"We're in a place today where we have so many cameras, so much tech, there's not as much ego," Taillon said.

His first focus was on his lower half, becoming less "quad dominant," he said, and more "glute dominant." He was retraining his kinetic chain from the ground up: from the feet, through the hips, the shoulders, the arm, and ultimately the hand, the tail of the whip.

In his old motion, Taillon felt his arm was being "hung out to dry."

"My hips weren't working efficiently and that, in turn, was leading to my arm being left behind my body," Taillon said of his old motion. "My arm was not feeling connected."

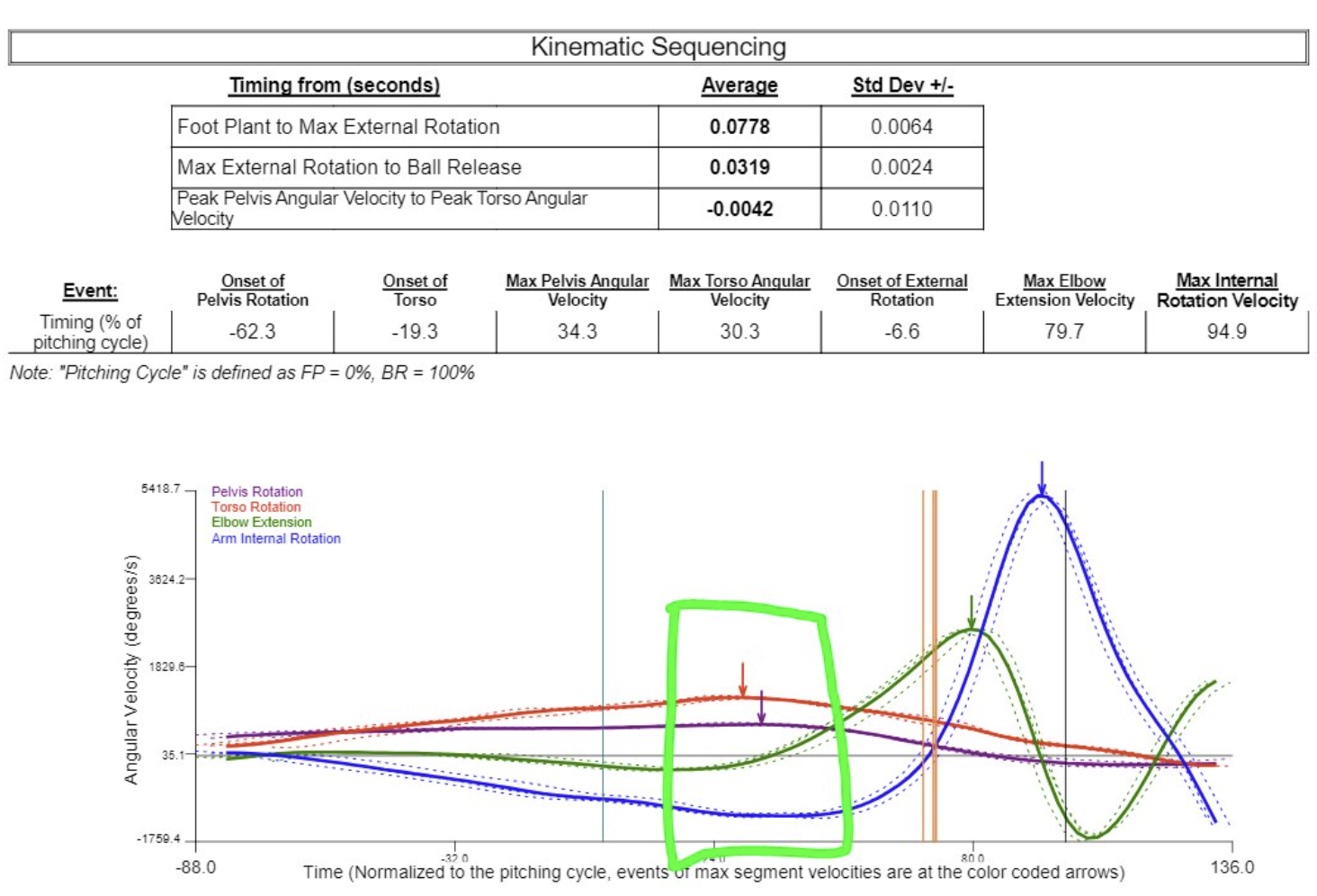

As Boddy explains, a report from a biomechanics lab will show a pitcher if his body is sequenced correctly. For instance, in a Driveline lab, the report will show a pitcher when his peak torso, shoulder, and arm rotational velocities occur. Those peak speeds should not all come at the same time. They should come in a 1-2-3-4 order from the base up. Taillon's sequencing was out of order. To better connect his upper body to a stronger base, he needed a shorter arm action.

The following report from Driveline Baseball is an example of a 2-1-3-4 sequence:

At the Pirates’ indoor training facility, Taillon began a weighted-ball regimen that included throwing malleable, sand-filled rubber balls, known as plyoballs, into the wall over and over again. In one drill he began with his back to the wall and contorted his upper body with the plyoball to throw the ball into the wall from an odd angle. He did another drill in which he stepped back like a quarterback and thumped ball after ball into the wall, echoes bouncing around the walls of the two-story complex.

"My arm started getting shorter, shorter, and shorter," Taillon said. "I was like, 'Maybe I'm onto something.'"

Taillon seems to have drastically shortened his arm path pic.twitter.com/ujwBs26Sj2

— The Yankees Zone (@TheNYYZone) January 25, 2021

In his new delivery, by the time his front foot planted into the ground, the ball was nearly out of his hand. In his old delivery, when his front foot hit the ground, his hand was still lagging behind his head.

"Before, my body almost felt like it was doing its own thing and then my arm was doing its own thing to find a way to create velocity," Taillon said. "If you look at my old video, my hand was so far away from my head. My hand was so far away from my body. My arm was so disconnected from my body."

He cringes when he looks at his old arm action.

He'd been through hell over the decade. He'd beaten testicular cancer. He'd had Tommy John twice, endured a hernia surgery, and even taken a line drive to the head. As he progressed through the new throwing motion, something unfamiliar happened: he felt good on the days after he threw. He felt like he could keep throwing and throwing. He was no longer in pain.

With two outs and holding a two-run lead in the ninth inning in Game 7 of the ALCS last October, Tampa Bay reliever Pete Fairbanks used an impossibly short arm action to unleash a slider that Houston's Aledmys Diaz lofted into right field. It almost looked like Fairbanks took the baseball from his back pocket and just whipped his hand forward. When the ball came to rest in Manuel Margot's glove for the final out, Fairbanks extended both his arms and rushed to meet catcher Mike Zunino in front of the pitcher's mound. Fairbanks helped send the Rays to the World Series.

Three years earlier, as a minor leaguer in the Texas Rangers organization, Fairbanks was dealing with a sore elbow when he was struck by what he saw on a June night in 2017. Boston Red Sox reliever Joe Kelly threw a pitch 104 mph with a noticeably shortened arm action. How did he do that? Boddy, Giolito, and the Cleveland arms and coaches weren't the only people in the industry asking this question.

Fairbanks had already returned from one Tommy John surgery. That August, he would undergo his second. Like Taillon, he is now in the small club of two-time TJers who've shortened their arm motions to lengthen their careers.

"Kelly used to be super long in the back. I saw that and said, 'OK, I think I am going to do this,'" Fairbanks said.

Fairbanks is a curious player interested in data and information that could help him. The Moneyball movement hadn't interested him much. That helped teams win on the cheap. The second data revolution, one that could help players, fascinated him. How could tech and data help him master his mechanics and ball flight?

Even before his second surgery, he decided to remake his delivery. He learned more about the "pocket path" invention of Dave Coggin, the former big-league pitcher turned instructor who helped Kelly. Coggin believed in patterning a pitcher's throwing motion after shortstops'. Coggin studied pitchers who had long, successful careers and found many of them shared a couple of common experiences as young amateurs: many had either played quarterback or shortstop and brought that shorter arm action to the mound.

He saw more kids being taught to have long, out-of-sequence motions at the youth level. Coggin didn't agree with all the weighted-ball concepts, so he wanted a different constraint. To teach a shorter motion without a weighted ball, he created what is essentially a pouch on a belt that holds a baseball. When used, it forces pitchers to be short in taking the ball from the pouch and throwing from there. They end up throwing like a quarterback or a shortstop. Or like Fairbanks.

Fairbanks also found a local pitching coach in St. Louis, Andy Marks, who believed in constraint training. As Fairbanks began throwing after surgery, Marks had him make all sorts of unusual throws, including a drill where he threw with his left knee on the ground while maintaining balance.

"It's super tough to get the arm extended behind you and bring it up to a spot where you can launch forward and throw," Fairbanks said of the drill.

The methods started to rewire his muscle memory and his motion got shorter and shorter.

"It's like a quarterback," Fairbanks said. "He has to make all these different throws but he throws the same - he gets his arm up and throws it. (My motion) is more quarterback-y and shortstop-y than the pitchers of the 1980s and 1990s."

So if it's like how a quarterback throws, Fairbanks thought, why not also throw a football? So during quarantine and last offseason, he and Rays teammate Josh Fleming, a fellow St. Louis resident, made regular short commutes to the football field of St. John Vianney High School off I-44 in Kirkwood, Missouri, and uncorked spiral after spiral.

Fairbanks doesn’t believe any pitcher perfectly replicates mechanics pitch to pitch. What he wanted to do was be more consistent with timing, which he believed the shorter arm action would allow. What followed was not only a more compact and coordinated motion but a spike in velocity. As with Kelly, Fairbanks' velocity surged. Suddenly he was sitting at 98 mph. His strikeout rate doubled. He was striking out 15 guys per nine innings. The Rays noticed. They acquired him by sending Nick Solak to Texas in July 2019.

While any sort of pitching delivery will never be risk-free - Fairbanks missed time with a shoulder strain earlier this season - he believes his arm motion is a better way to throw. The next question becomes: should pitchers who are healthy and performing adequately consider such change?

There are pitchers with longer arm actions in the Reds organization Boddy won't tinker with. Rays pitching coach Kyle Snyder said he would never suggest the change to a healthy, productive pitcher with a long arm action. Yet he believes shortening the arm might indeed be a better way to throw. Snyder compares the motion and logic to that of throwing a shot put. No one would ever attempt to throw it with a long arm action.

"It's completely a theory, but I think it is somewhat supported over time with Gioltio now and some other guys," Snyder said. "It may in fact be a stronger position to throw from. And there will be more."

As Taillon watched Fairbanks buzzsaw his way through the postseason last year, he only gained confidence in his own change.

Before making his first start this April as a Yankee, Taillon spoke to reporters via Zoom and offered a sober assessment of what he believes he can salvage from his career.

"From being the second overall pick coming out of high school, looking back now at 29, I'm not going to be a 100 WAR pitcher now," he said. "I've come to grips with all that, the stuff you dream of when you're drafted, winning 20 games for 15 years straight, and stuff like that. But I'm happy to be here. I do feel like there's a lot ahead of me."

Adding to his own reinvention, the Yankees also presented him with a plan to maximize his skill set. It included more fastballs up in the zone, and a lot of curveballs, which he's always thrown well. Taillon finally had a roadmap and delivery to become the pitcher he always could have been.

Seven hundred and seven days after his last major-league appearance, Taillon struck out Baltimore's Cedric Mullins with a 95-mph fastball. One of the surprising changes is that he's added spin and thereby lift on his fastball, he says. While his return's been up and down so far, his strikeout rate's at a career-best level early this season. He said he's feeling more comfortable.

"I wished I would have learned how to use my glute and shorten up a little earlier. I don't think I would have had two Tommy John surgeries," Taillon said. "I was picked between Harper and Machado. I’m clearly not going to be either of those guys. Here I am. I can't change it. It's almost a little freeing. I can still have a great career and contribute to a winning team. … Maybe there's not a track record of guys with two Tommy Johns, but guys have gotten better with age like Charlie Morton."

For nearly a decade, the way he threw never gave him much of a chance. Now, he believes he's found a better way to throw. He believes he's found a way to be the best pitcher he can be.

Travis Sawchik is theScore's senior baseball writer. He is the co-author of the book The MVP Machine, which delves deeper into the ways baseball players are using the current wave of technology and data to improve.