TV's challenge: How to work in the tight spaces of the new pitch clock

When Chris Withers first learned of Major League Baseball's decision to adopt the pitch clock, his immediate thoughts turned to his own quality of life.

He's passionate about his job and regarded as one of the best producers in the industry, but if games are 25 minutes shorter, he figures that could mean the equivalent of four fewer days spent in the NBC Sports Chicago truck, where he produces White Sox television broadcasts.

In early February, he began to understand how dramatically his job - and the nature of broadcasts - was about to change.

Attending a seminar in New York for broadcasters, they were shown some televised minor-league games from last season and examples of the pace changes. He saw firsthand how difficult it was going to be to squeeze in replays, graphics, promos, and ads with only 30 seconds between batters and 15-to-20 seconds between pitches. It's his 18th season on the job, but he began to lose sleep some nights.

On Feb. 25 during the White Sox spring opener against the San Diego Padres, he got his first taste of working with baseball's new pace. It was even more jarring.

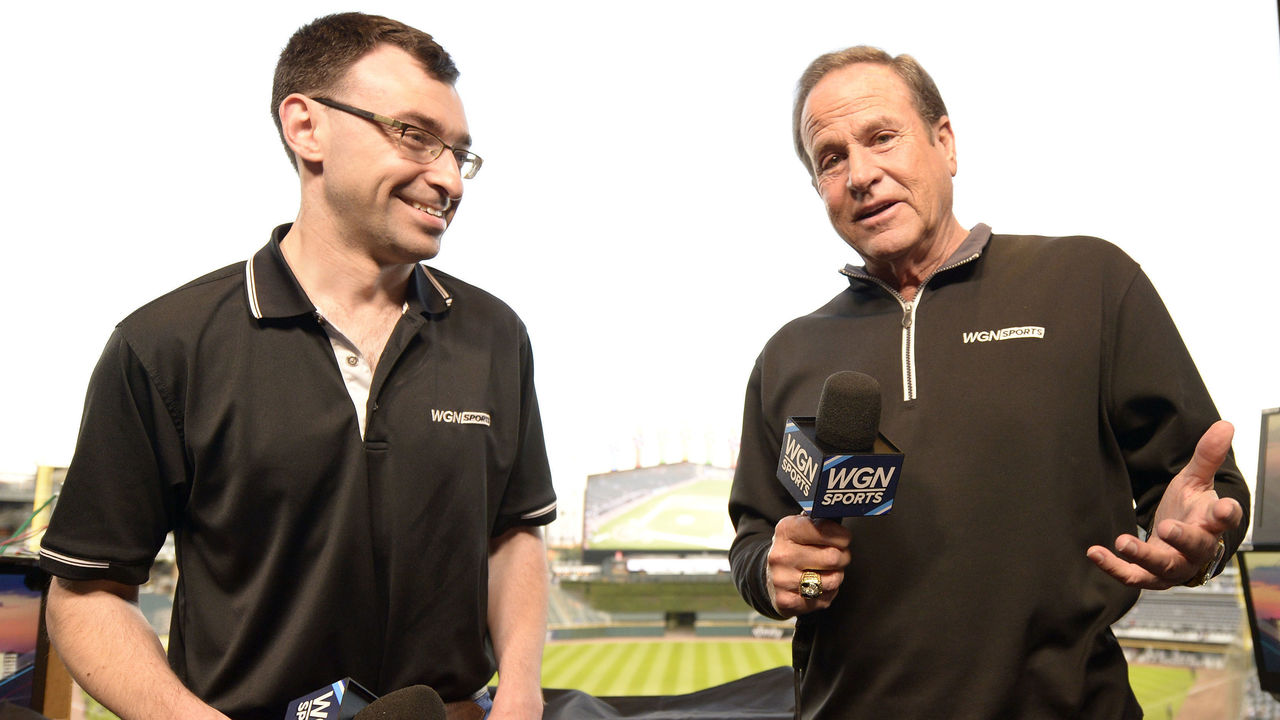

After the game he immediately met with White Sox play-by-play voice Jason Benetti.

"We are covering a different sport now," Benetti said. Withers agreed.

"What Jason said keeps hitting me," Withers told theScore this week. "Our jobs are completely different now. Having done three spring training games, it is tenfold more impactful than anything I thought it was going to be just from talking about it."

Those following MLB's spring action have seen how some players are struggling to adapt to baseball's new pace and rules, but they're not the only critical industry employees facing a major adjustment.

During that first game, Benetti felt the change immediately.

"I said to Stoney (color analyst Steve Stone) on the air, 'Are we talking faster? I think we're talking faster,'" Benetti said. "It was like, 'Wow,' the cadence and rhythm and the pace of everything we do in the booth felt different."

The majority of fans consume baseball through TV. How we watch the game is going to change - a lot.

Closed-book exam

Minor-league games were 25 minutes faster last year with the pitch clock. This spring, theScore found that the first 40 major-league exhibition games were 21 minutes quicker compared to last spring.

The amount of commercial time between innings and pitching changes is the same. That means just about all those minutes being shaved off games is coming from time between pitches - time that broadcasters have filled for years with anecdotes, extended replays, pretaped interviews, promotions, or even dead air.

Even something as routine as a play-by-play voice knowing when to hand off to the color analyst becomes more complicated.

"Everything is sped up," Benetti said. "(Stoney) joked the other day, 'I've been working between games on making my stories shorter.'"

Benetti said he doesn't expect there to be much of an issue between him and Stone. "Steve is so good at pausing for a pitch and calmly picking up the story. I've had analysts - and I think both styles work - that talk through the pitch, and if it gets put in play they just stop. Steve has this way where he smoothly pauses, the pitch comes, and if it's fouled away he continues with his story. If not, I pick up the action. He's so good at it."

Benetti believes his biggest adjustment will be in his preparation. Broadcasts are no longer open-book exams.

He's getting a bit of a head start in adjusting as he's also currently calling college basketball games for Fox. I spoke with Benetti as he arrived in Boise from spring training to call the Big Sky Conference title game.

When calling a college hoops game, Benetti doesn't have much time to look at notes. He must memorize facts he might want to retrieve on air since he has to keep his eyes focused on the frenetic, free-flowing action.

In the baseball booth during his first seven seasons calling White Sox games, he had plenty of time to search through a document of facts he'd prepared to find a particular note.

"Previously, with the ability to just wander between pitches, while Steve is talking and I'm listening to him, I could look in my notes and say, 'Oh, here that is,' if I needed to jog my memory," he said. "For instance, if we are talking about a guy and I wanted to confirm a statistic, or where somebody was from, you just had the time. Now you don't.

"I literally said after the first (White Sox spring) game we did that I feel like we're doing a basketball game."

On the north side of Chicago, Cubs play-by-play voice Jon Sciambi is also calling college hoops games this spring.

"After the first college basketball game I do every year, when it ends, it's jarring," he said of basketball's pace. "It ends and I'm like, 'That's it? We're done?'"

His baseball experience is now more like that, too.

Sciambi knows he'll have to become more efficient. But he also believes there's a benefit for broadcasters in working within tighter time constraints.

"The way the games have gone, the extra space is just an invitation to say dumb stuff," Sciambi said. "(Now) it's use your best stuff. I certainly hope our broadcasts follow that, and I follow that."

What he and Benetti agree on: it's not the play-by-play voices nor their analyst partners who face the greatest tests this year. Rather, it will be the producers: Withers and his peers behind the scenes.

A new reality for replay

Consider replay, a staple of any sports broadcast given how much dead time there can be amid the action. But the genre is about to be disrupted.

"I think the home run is going to be a big one," Withers said. Last season, a typical replay sequence after a home run might include six or seven different looks at the swing, outcome, and reactions.

"If it's a home game, and if it's a White Sox home run, my philosophy is going to change to the point where we are just going to stay live and cover the energy in the ballpark, the high-fives in the dugout," he said. "Because even if I get into a replay the second he crosses home plate, which I don't really want to do, I want to at least milk that a little bit.

"The replay sequences I've done in the past would have to be dramatically cut down. At most that's a swing, ball out, and one reaction. And even that would be tough now with our super-slow-mo camera.

"I'm very interested in what I figure out. Because talking to you right now, I haven't even figured out exactly what I want to do. And then there's the other (replay types) that happen between pitches that aren't home runs."

Withers isn't shy about experimenting, but he faces a clear constraint to work around. The cardinal sin of a baseball broadcast is missing a pitch, he said.

This spring, they've begun to try more double-box replays, where most of the screen remains on the live action and replays appear in a smaller second box. They even branded the replay box "Steve's Replay Corner." (They're not sure if that graphic and branding will stick.)

"I'm trying to watch a lot of spring training games and see what everyone else is doing," Withers said. "There was an instance in a Yankees-Toronto spring training game where there was a great running lead by the runner, who took off and stole second. They went into that replay look, and came out, and the pitcher was already halfway through his delivery - and the runner was halfway to third base (on another steal attempt). So that made me think, 'Should we stay live there?' But I also thought it was an important replay to show."

He thinks the double-box setup may be the new normal for replay. "I think we could be onto something," he said.

Drama: A lost art?

One piece of visual evidence pitch-clock haters keep citing is the production of Bryce Harper's home run in the NLCS last fall, the shot that powered the Phillies to the World Series.

During the lulls between those high-leverage pitches, Fox cameras were able to capture the scene in full: Harper staring at his bat, then refocusing on the pitcher; the anxious crowd shots; pacing in each dugout. Tension was built through multiple cameras and production sequencing during the seven-pitch, four-minute plate appearance.

But such productions will no longer be possible.

"It's going to be tough to build the drama. That's been another concern of mine," Withers said. "I don't think we'll know until we get into a late-game situation. But there's no question that (the pace) is against us. It's just not going to be feasible to get that tight shot of Bryce Harper's face, tight shot of the pitcher, then the praying hands in the stands, then the runner at second who is the game-winning run, and then get back to camera No. 4 for the pitch.

"Sure, you can do it quicker, but just speeding up that sequence kills some of the drama. Do we have to lose one of our shots? Yes. I feel for the great directors out there who find all those awesome moments and tell those amazing stories when the game is tight. The simple matter of fact is those sequences just got shorter. You are going to have to pick the absolute best shots. You've probably lost two or three of the ones you're used to doing in a normal sequence."

As a narrator of these dramatic moments, Benetti is thinking about his role, too.

"I was thinking about the NBA Finals. Somebody hits a big three, the coach calls a timeout, and that's a place where you get all the drama of the arena," Benetti said. "I know some (MLB) players have suggested, 'Well, what if the pitch clock were longer in the eighth or ninth innings, or (we) didn't have it at all in the eighth or ninth innings.' I've thought: What if you just had a couple more timeouts? That would solve all of the drama issues, I feel. Batters, they use them. Regardless, whatever the rules are, there is drama in the ballpark.

"I know the changes are to make sure more people are interested in baseball so there's going to be the cost-benefit analysis of, 'Yeah, it might be something where we lose a little bit of this,' but I also think there are going to be answers. That's where I lean. There will be new answers."

Clockwork

TV crews are still figuring out how to best incorporate the pitch clock itself into broadcasts. In the first three White Sox broadcasts this spring, Withers was asked to handle the clock differently.

In the first game, MLB asked broadcasters to not show the clock until seven seconds remained. NBC pushed back and showed it at 15 seconds in the second game.

"Then our new edict was 10 seconds," Withers said of Wednesday's telecast.

Withers said MLB doesn't want the clock to be "this front-of-the-show-type thing."

Some broadcasts have shown the actual digital clock behind home plate. Others have incorporated the countdown within their score graphics.

"We're still trying to figure it out," Withers said. "That's what spring training is for."

The unknown

Benetti knows there will be complaints no matter what broadcasts look and sound like early this season.

"Because Twitter exists, there will be people with grievances," he said.

But that's always been the case with anything new and he's excited to experiment. He cited Fox's pioneering of persistent score graphics in the 1990s.

"People hated it at first, but now you cannot live without it on the screen," he said.

He also noted another Fox innovation: the glowing hockey puck, which never caught on among NHL fans.

There will be trial and error.

"The thing I keep coming back to is there are people in the truck who take a very high level of pride in documenting the drama of a sporting event. It's their entire livelihood," Benetti said. "I know (Withers) lives and breathes it. They are going to find a way. I don't know what it will look like. It might be better, it might be worse for a while for people. There are going to be hits, there are going to be misses, but you have to innovate. Someone is going to land on, 'We needed this the whole time.'"

A self-described TV nerd, Benetti watched some Stone and Harry Caray broadcasts from the 1980s and early 1990s on YouTube this offseason, games that had a pace more like what we're expecting this season.

"I do think you can hear in Harry and Steve their level of comfort with the pace of the game," Benetti said. "That was just how it was played."

"It's a little bit like that flip-book that shows a president after he's been in office for eight years and how gray he got. Day to day, you cannot see it, but you see it at some point. We got to a threshold level where we just kind of basked in the amount of time we had and we used it how we used it. I think we'll all adapt."

What they all agree on: baseball needed this change.

"How I sum up the (pace issue) is like this: It was taking too long for nothing to happen," Sciambi said. "That's what baseball is when it is at its worst. And when it's at its best, it's as spectacular a sport that's ever been created."

Withers said three friends from his fantasy football league reached out to him and said they're more interested in baseball this spring. ESPN's Ben Cafardo reported the network just had its most-watched spring training game since 2016.

"I think it's going to make the game, and also watching baseball on television, a beautiful sport," Withers said. "It is already a beautiful sport. But I think it's going to make it crisp. I think (in past seasons) people, after a couple hours, after two-and-a-half hours and it's the sixth inning, people just change the channel. So what it does now, there's so much more action, there's a pitch every 15 seconds, there's less time for people to think about changing the channel."

ESPN is scheduled to broadcast the White Sox season opener in Houston, so Withers and Benetti will have to wait until the second game of the season to fully enter this new era of broadcasting.

Benetti has plans for his Opening Day off day in Houston.

"I am going to watch literally all of the broadcasts," Benetti said. "We all have this comfort of what baseball on TV was. What is it going to look like from a totally fresh perspective?"

Benetti says he's a "big puzzle guy." He loves the clock in part because it seems likely to draw more new fans in, and draw lost fans back to the game. He also loves it for professional reasons: it's a new problem to solve.

"I love the idea that we're challenged into doing something else, something different, something with a new rhythm and cadence," Benetti said.

What will that look like?

"I don't know," Benetti said. "But that's the fun of it."

Travis Sawchik is theScore's senior baseball writer.