NFL owners want a quick labor deal. Here's why the players should slow down

Dear NFL players,

The leadership of your union, the NFL Players Association, has moved to send a proposed collective bargaining agreement to you and your fellow members, with a vote expected in the next few weeks. A simple majority is all it takes to ratify the agreement. The new deal would run through the 2029 season and add a 17th regular-season game, in exchange for some modest concessions from the owners.

But before you vote, ask yourself this question: What's the hurry? The current agreement doesn't expire until March of next year. Yeah, I know: Your union's executive committee spent 10 months bargaining, television executives and internet streaming services are waving blank checks at the league, and some of that Serious Money will also flow in your direction. But notice who's been really eager to get this thing done and then consider why this is so.

On a moment's notice last week, all 32 owners flew to New York City to approve the agreement on their end. The rationale for their urgency has been explained through the press in recent weeks: Locking in a deal now would provide labor peace that can be sold to the TV networks, which are thirsty for the NFL because the NFL is a ratings monster. At the root of all this is the 17th game, which is an extra week of programming.

Also, despite a recent dip, the stock market has remained strong over the long haul. But there's a presidential election looming, which means ratings might slip this fall, and who knows what might happen to the markets if the occupant of the White House changes. The owners basically want to get this deal done while the getting is good, because any of the above factors could negatively affect the league's primary source of revenue.

This is nonsense, though. There is nothing - absolutely nothing - to suggest the public's ravenous interest in watching the NFL is going to wane any time soon. I mean, 28 of the 50 most-viewed primetime shows last year in the age 18-49 demographic were NFL games. Also, the NFL has been immensely popular for decades, which ought to offset the idea that some Democratic bogeyman is going to make the league less popular after the election - a forecast that likely reflects the owners' political preferences more than any solid economic indicators.

And it's not like the networks have the guarantee of something like a "Cheers" reboot in the hopper as a ratings replacement. The networks need the NFL more than the NFL needs them, and the owners know this. They want you to think you need to rush to do this deal, or else.

Which brings us to the length and the revenue split of this proposed CBA. At 10 years, the deal would give the owners exactly what they want: long-term cost certainty, even with the players' share of total revenues climbing from 47% to 48.5% in exchange for adding that extra game, which the players have long stated they'd be against because of the health and safety risks.

Gambling and streaming services will factor into the revenue pie in the decade ahead. So why agree to a pact that doesn't include an opt-out that would allow you to reassess things in a few years? Why lock in your take for an entire decade instead of insisting on a gradual increase that eventually reaches 50% toward the end of the 10 years? The previous CBA, signed in 2006, had an opt-out clause. And the owners exercised it as soon as they could before locking out the players during the 2011 negotiations.

"The problem with a long-term deal is things change," Villanova University law professor Andrew Brandt said this week on his podcast, "The Business of Sports." Brandt, an ex-Green Bay Packers executive and former player agent, has been on both sides of the table. He cut right to the chase when he said, "The NFL is being very strategic with this deal." Heed those words.

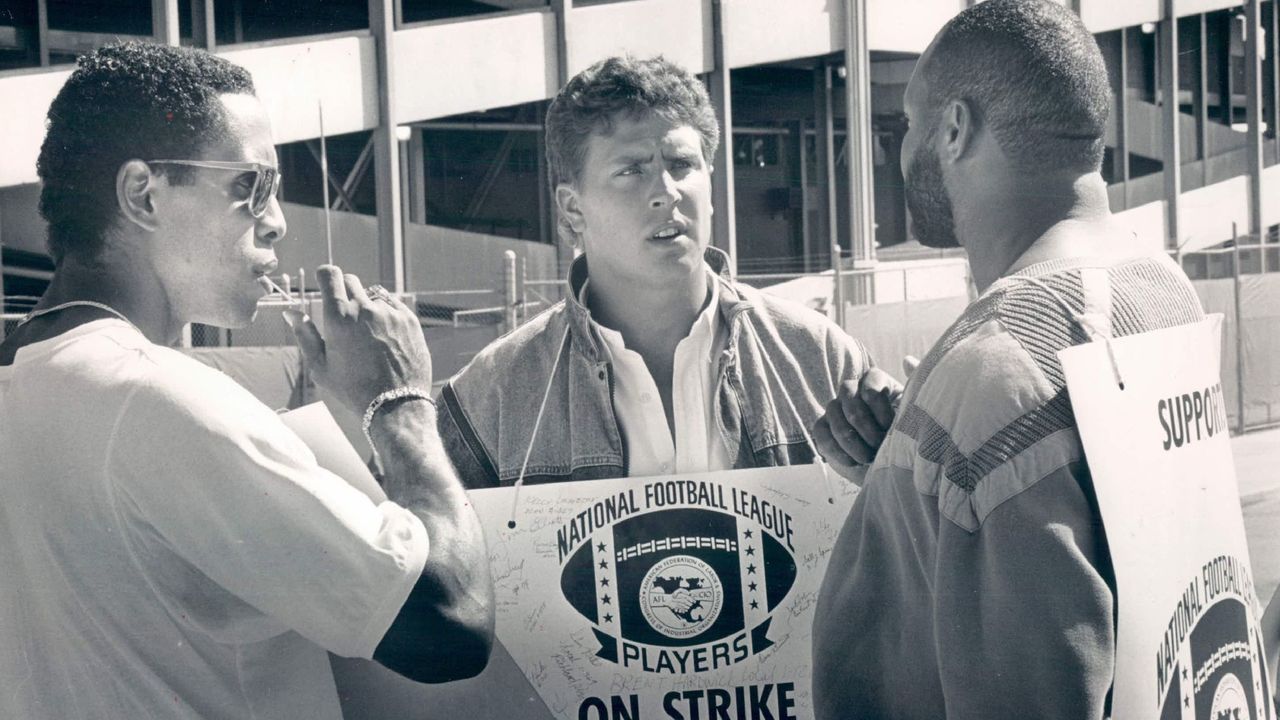

I'm sure there were items the NFL made non-negotiable. But you have to consider who you're up against. The league's owners have long made a sport of dividing and conquering you. Your predecessors went on strike multiple times in the 1970s and 1980s, going so far as to sacrifice game checks in 1982 and 1987. The owners' response in 1987 was to field literal replacements to break your ranks.

Yours was the last of the four major North American sports leagues to adopt free agency - but only after your union briefly dissolved itself so individual players could seek relief from the courts. You also play in the only such league without guaranteed contracts, and even if that's more the result of individual bargaining custom than anything specifically brokered by the union, it's still a fact. As is your risk for injury compared to those other sports.

Free agency began in 1994, and none of management's fear-mongering about how it would ruin the game proved to be true. The exact opposite has happened, in fact. Yet the owners have never stopped prioritizing their profits and their ability to exert control over you, from (among other things) the way they manipulated the data on brain trauma to Roger Goodell's weaponization of his total disciplinary authority to that short-lived national anthem policy they cooked up without consulting any of you.

The anthem policy died before it could be implemented because your union filed a grievance, but it's hard to believe it didn't serve a strategic purpose - that the league's sudden about-face and show of magnanimity wasn't just another bargaining chip for the long game. And here we are.

What appears to be one of the best features of this deal is actually a window into the way the owners can subtly divide your union. Minimum salaries for rookies will increase by $100,000 this year, and by $90,000 for other minimum-salary players, with another bump in 2021 followed by slower growth in the years to follow. For all the talk about the NFL being a league of millionaires, roughly 60% of you play for the minimum. For rookies in 2020, under the current CBA, that amounts to $510,000. An extra $100,000 would represent a boost of nearly 20%, which is one hell of an incentive for someone with limited earning power in a league in which the average career spans approximately five seasons.

I know you don't want to hear this, but football will likely be done with you when you're still in your 20s. Nate Jackson has written eloquently about his time as a player on the league's fringes. Pay attention to him:

NFL Players: No matter what you think of the proposed CBA, don't be swayed by an extra 100k per year. Here is the truth about your football $$: IT WILL ALL BE GONE EVENTUALLY. Whether thats 3 years, 5, or, if you're lucky: 10. Either way, it will be gone. Question is, then what?

— Nate Jackson (@NathanSerious) February 26, 2020

The "Then What?" question can be addressed in the CBA. Health care, worker's comp, 401k, annuities, life skills, career transition services, continuing education, counseling, etc.. Now is the time to ASK FOR WHAT YOU WANT. If you don't ask, you won't know.

— Nate Jackson (@NathanSerious) February 26, 2020

Again, this proposal also locks in those costs to management for a full 10 years. And there aren't any adjustments to the rookie-wage scale, which strips draft picks of any bargaining power for up to four seasons - or five, in the case of first-round selections - with no chance to negotiate for the first three years. The league is basically leveraging the fact that most careers are short and tenuous.

"This is the strategy - I mean, it's pretty transparent," Brandt said on his podcast. "The owners said, 'We can get to the rank and file - they're the majority, not the stars.'"

The league had a plan for the stars, too, of course. By capping additional salaries for the 17th game at $250,000 for players currently under contract, the league positioned itself to offer an easy concession. After all, this provision was going to affect very few players (all of whom are already well-compensated), and as NBC's Peter King noted, there's nothing to stop these stars from bargaining for something better with their current teams. Lo and behold, during Tuesday night's meeting with the NFLPA's executive committee, the owners agreed to scrap the cap.

Even the proposed changes in minimum team spending - 90% of the salary cap in rolling, multi-year increments - are illusory. Under the current deal, teams are required to spend 89% of the total salary cap across four-year spans. This has allowed many of them to squirrel away cap space and to roll it over. But as Jason Fitzgerald of Over The Cap has calculated, "Teams are already spending on average over 100% of the cap and no team has been under 90% in any four-year window. All this does is allow some teams to tank for a period of years if they feel like it."

The NFLPA's fact sheet also refers to a "new workers comp process" that's supposed to make it "easier" for players to file claims. But Brad Sohn, a Florida attorney who represents several players with concussion settlement claims, told me players need to examine the exact language in the CBA - and to have a lawyer look it over - to be sure they're not signing away any rights without knowing it.

Come to think of it, every one of you should read as much of the direct source material as possible and talk to a union leader about specifics. The fact sheet the NFLPA made public is vague in many ways. If an executive committee member or team rep is convinced this deal is worth accepting, have him walk you through an explanation. Ask questions.

Don't take it from me; here's Eric Winston, the NFLPA president, on what you ought to do next:

vote on it and every vote counts.

— Eric Winston (@ericwinston) February 26, 2020

I’m happy to hop on the phone with any player at any time and anyone is always welcome to come to our annual Rep meeting or to join any of the numerous calls we have had or will have in the future. Let me know.

Or from Packers quarterback Aaron Rodgers, who explained his "no" vote as a player rep in part by stating that "we have made this decision with only an abbreviated version of the deal and that isn't good enough":

My thoughts. # pic.twitter.com/VOmCSNiI4f

— Aaron Rodgers (@AaronRodgers12) February 26, 2020

There's some good stuff in this proposal, from better workplace rules that include even fewer padded practices to changes to the marijuana policy to improved pensions and pension eligibility, plus additional health benefits and 401(k) matches. Second-round picks could be eligible for performance-based pay, two more players could be active on game day, and there are two more spots on the practice squad, with veterans eligible to take them. A "neutral decision-maker" would handle "most" discipline cases, though Goodell would reportedly still be the appeals officer, according to The Washington Post's Mark Maske.

But when the big-picture items include a modest increase in the players' share of revenue that remains fixed for 10 years, is all of that enough to offset the health risks of a 17th game? That's the other question all of you need to keep in mind.

Don't forget that the benefits your union has already achieved on your behalf - such as voluntary offseason workouts - are often held against you, with management's gripes frequently laundered through the media when any of you try to take advantage of these collectively bargained provisions. But forget the noise. You earned those rights.

It's always been a challenge to keep your large, disparate membership united in pursuit of a common goal. But you've prepared for this, and your union leadership ultimately answers to you, rather than the other way around.

Remember: Fans don't tune in to catch a glimpse of Jerry Jones stifling a scotch burp whenever the cameras cut to him in his luxury box; they tune in to watch you play football. You play in a league that generates approximately $16 billion in annual revenues. And in the decade to come, that number is likely to keep growing. The owners want you to assume the bodily risk of an extra game. Ask yourself what that's worth.

Sincerely,

A football fan

Dom Cosentino is a senior features writer at theScore.