How it started: 50 years ago, the Capitals were expansion jesters

An unknowing bystander watching players skating victory laps in the empty Oakland Coliseum Arena on March 28, 1975, might have assumed they had just set a record. The NHLers, who were in various stages of undress following a 5-3 win over the California Golden Seals, were taking turns hoisting an old, green garbage bin overhead and ceremoniously presenting it to one another after each lap. Closer examination of the makeshift trophy would have revealed it was signed by each of them.

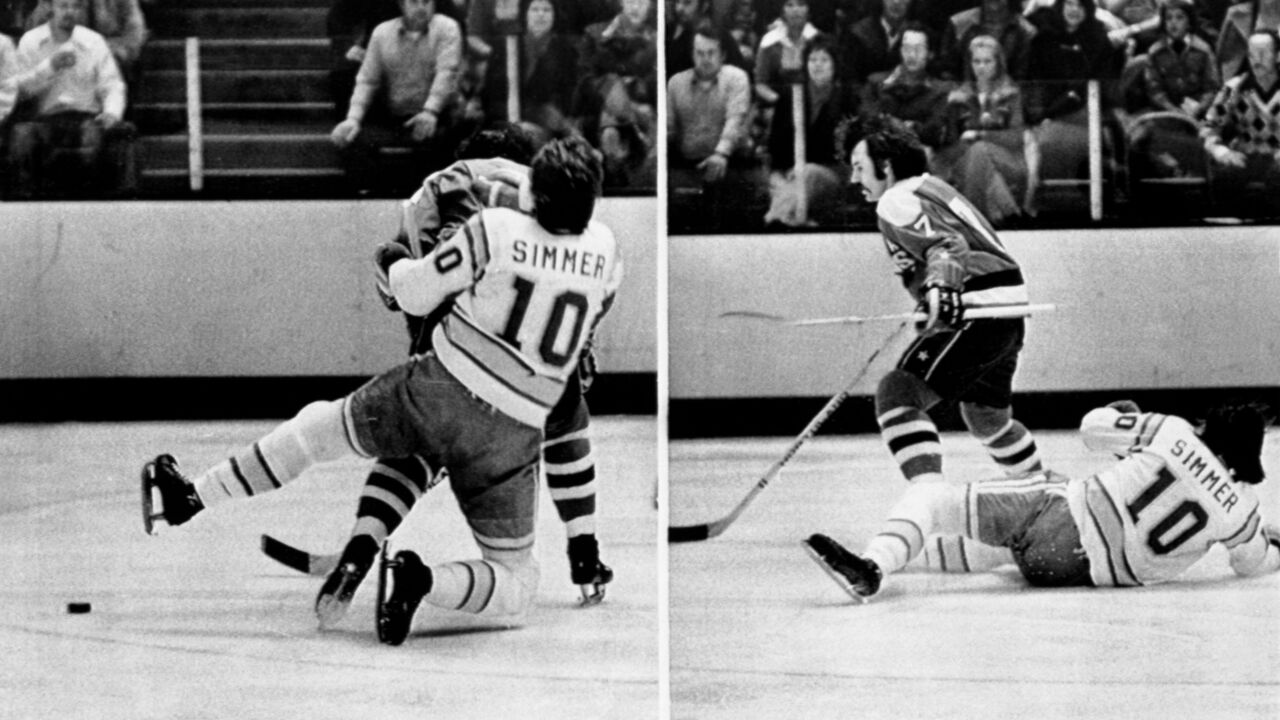

The skaters: Doug Mohns, Tommy Williams, Yvon Labre, Ron Lalonde, and the rest of the Washington Capitals' inaugural roster. Indeed, they had just capped a record - one that stood for nearly two decades. Washington's ragtag expansion team had just ended an NHL-worst 17-game losing streak that wasn't broken until 2004. The winless run helped them to an 8-67-5 record that still stands as the worst in NHL history.

But that moment was about love of the game.

"They'd already turned all the lights off in the arena, but we still had our skates on, and we went back out," Lalonde recalls. "That was our Stanley Cup."

Fifty years before Capitals captain Alexander Ovechkin would become immortalized as the NHL's all-time leading scorer, and long before the organization's players lifted the real Stanley Cup for the first time in 2018, small but monumental wins created the framework for hockey to flourish in Washington.

"We were getting clobbered most nights," Lalonde says. "But you knew that at some point this franchise was going to turn around. The fans were great. They just wanted to see players hustle and give it their best. They weren't expecting us to win every night, and they showed up."

Numerous factors worked against the Capitals that first season. "Expansion in 1974 wasn't the same as expansion when Las Vegas came in," Lalonde says. More generous expansion draft rules allowed the Golden Knights and Seattle Kraken to ice competitive teams right away. But in 1974 the talent pool had been diluted by the World Hockey Association, and NHL teams had not yet begun to sign European imports.

Complicating matters, the Capitals were on the tail end of a 1970s expansion boom that impacted how the league ran its expansion draft. In 1970, the NHL expanded to 14 teams by adding the Buffalo Sabres and Vancouver Canucks; in 1972, the New York Islanders and Atlanta Flames joined; and in 1974, the Capitals were added alongside the Kansas City Scouts (later New Jersey Devils). Because of previous expansion drafts, the existing owners in 1974 convinced the league to allow them to protect 15 players from their roster. For every player that was picked, teams could add one more to the protected list. In later years, the Capitals and Scouts would be forgiven more than half of their $6-million expansion fee because of the debacle.

"We got the 18th- or 19th-best player on each team in the expansion draft," Lalonde says. "And unfortunately for Washington, they took a number of older players."

Not every player arrived in Washington with the positive mindset Lalonde came with after being traded from the Penguins that December. "There were other players who were angry they weren't on the teams that had let them go and never really cared about putting out an effort," says hockey writer and historian Glenn Dreyfuss, who documented the team's early days in his 2020 book, "The Legends of Landover."

"There's a story about one of the first-season Capitals, Dave Kryskow," Dreyfuss told theScore. "He had a pregame conversation with Larry Robinson of the Canadiens. He said to Larry, 'What's the over-under on this game?' Robinson said 10. Guess what? The Canadiens won the game 10-0." Starting goalie Ron Low let in nine of those goals, followed by Michel Belhumeur who played the third period. Belhumeur still holds the league record for most games played without a win. (He was 0-24-3 in 35 games in 1974-75.)

The team also endured turmoil on the bench that first season, going through three head coaches: Jim Anderson, Red Sullivan, and Milt Schmidt. "It was a long year for the coaches," Lalonde says. He particularly remembers Sullivan, the Capitals scout turned coach, who announced at his introductory press conference he intended to be the coach of the Capitals for 10 years. Sullivan quit after 18 games, 16 of which were losses.

"Poor Red. I mean, he was a fiery, competitive, driven, individual player. He just couldn't take it behind the bench. He wanted to get out there and drill somebody when we were down a goal," Lalonde says.

Within this context of failure, players were expected to be part of creating a fan base. "Playing in the National Hockey League for an expansion team, it was our job to try and sell hockey in those early days," Lalonde says. "Nobody would know who we were, and hockey was sort of a strange thing. I remember one mall appearance that we had, they thought we were air hockey players."

Still, their efforts had an effect on at least one young fan in the stands. Dreyfuss was 14 years old when he asked for hockey tickets for his birthday in the Capitals' first season. He still remembers going with his dad - the tickets were third row from the glass and $8.50 each. "The Capitals won eight games that season. Out of 80. They happened to win that game. It was the first shutout," Dreyfuss says of the 3-0 victory over the fellow expansion team from Kansas City. Somehow, Dreyfuss found himself hooked on the Capitals, much like the rest of the small but devoted fan base that had begun showing up to games.

"They became like the New York Mets of the NHL. They were the lovable losers," Dreyfuss says. "In the 18,000-seat Capital Center, the 10,000 people who would show up would sound like 18,000. They didn't all know what they were watching, but they loved their team. There really was a love affair. That's most of the reason that the franchise survived."

The players who were able to see the season as an opportunity became legends. Just two days after skating that garbage can trophy around the ice, Lalonde etched his name in the record books by becoming the first player to record a hat trick in a Capitals jersey.

"That record is still there, that's one that Ovechkin can't break, no matter how much he does," Lalonde jokes.

Now, when he goes to Capitals games, he's amazed at the way the fan base has embraced the team. "I couldn't believe every fan coming to the game was dressed in a red Cap sweater - usually with the No. 8 on the back. That wasn't the case when we played."

Far from being embarrassed about the losing record in those early days, Lalonde is proud of the franchise's longevity. "When I see the fans now and how enthusiastic they are ... we must have done something right despite how poor our record was," he says.

Jolene Latimer is a feature writer at theScore.