The story of honoring Negro League history and a search for buried treasure

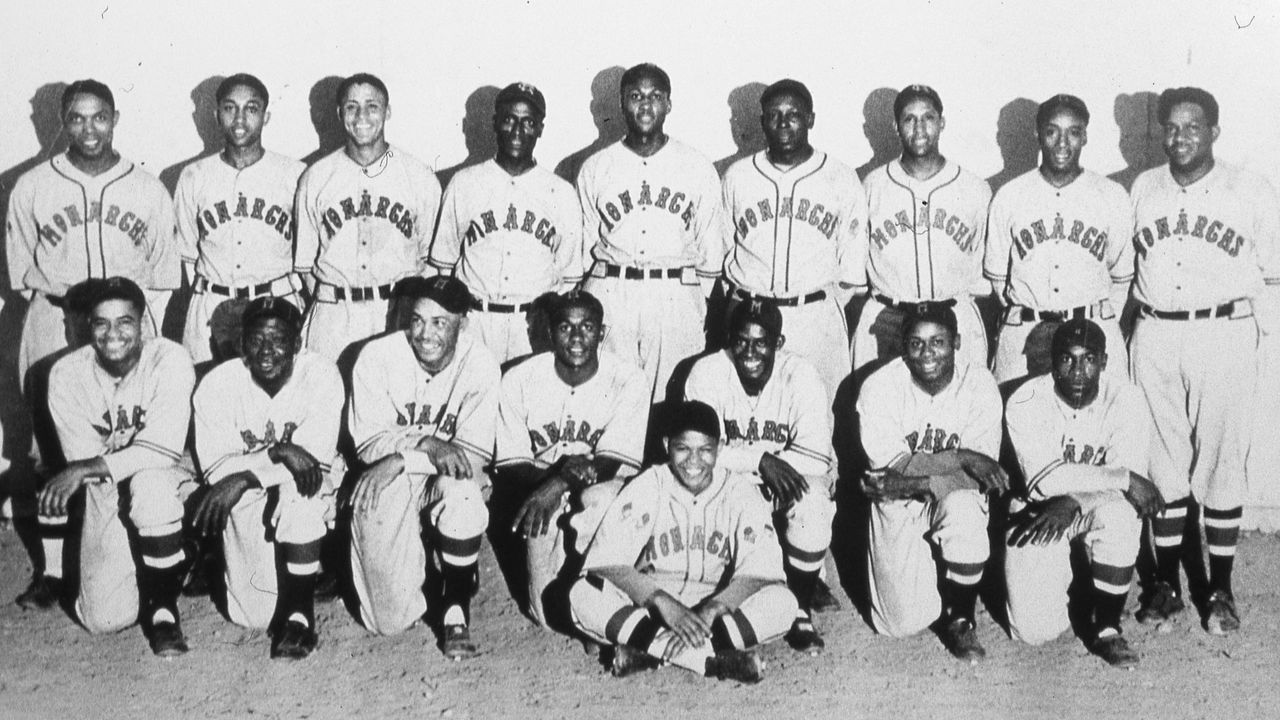

We traveled east along Lake Erie, on a search for hidden gems. Negro League players followed this same route in the 1930s and 1940s, moving along U.S. Route 20 in buses and caravans of cars until gasoline and rubber rations often forced them onto trains during World War II. The Pittsburgh Crawfords had what was considered at the time to be a luxurious Mack bus. We zipped along I-90 in my old Honda Accord. My friend Ray Danner and I were retracing a small part of their path, searching for their lost history.

Ray waited months for the public library in Erie, Pennsylvania, to reopen when pandemic restrictions eased so he could access its newspaper archive. I was curious about his quest, so I asked to come along on the trip from Cleveland.

Months earlier, Ray listened to Rob Neyer interview Scott Simkus, an author and researcher for Seamheads.com, a site where a small group of hobbyists came together to try to pull off the impossible: find every existing Negro League box score from the top leagues. The result of their work means there are no longer thousands of missing box scores, but hundreds.

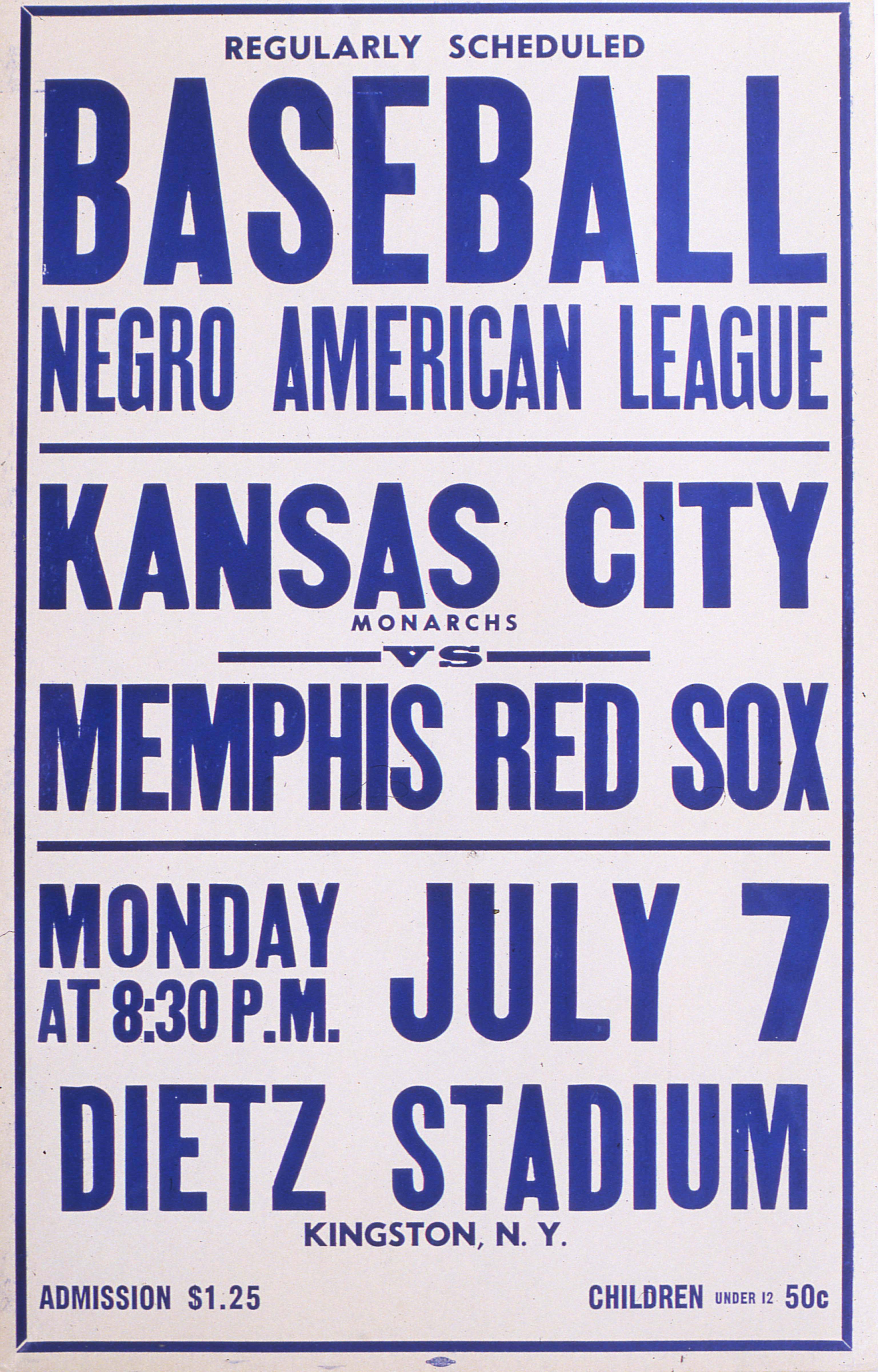

On the podcast, Simkus told Neyer they were certain there were missing games in places like Memphis; Zanesville, Ohio; and Erie. The missing puzzle pieces are mostly, now, in towns and cities where Negro League teams played during their lengthy tours. Seamheads was looking for volunteers willing to visit the libraries in these places and search the newspaper archives.

Erie? That's not too far away, Ray thought. He reached out to Simkus.

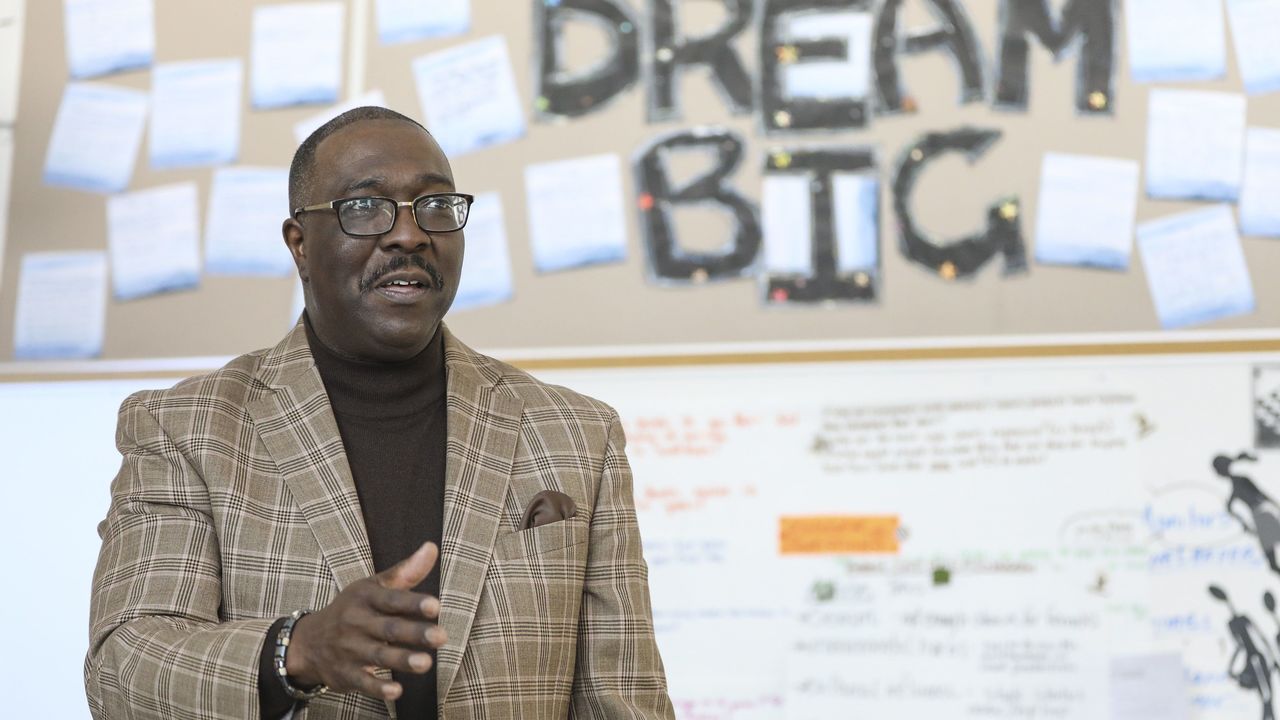

Ray, a history buff and member of the Society for American Baseball Research, knew Major League Baseball had elevated the best Negro Leagues to major-league status in December. Any box score Ray could unearth would eventually be included in official MLB statistics.

His work would help fill out the historical record at Baseball Reference, the preeminent statistical database, and one of his favorite online research tools. On Tuesday, Baseball Reference unveiled its new Negro League data with major-league status, data it licensed from Seamheads.

This was Ray's second trip to Erie. He recovered four box scores on his first trip and knew there were more to be found. Research like this can be tedious and underappreciated. What was the payoff?

"I like history, so it starts there," he said. "There is just an appeal to things that are forgotten or almost forgotten, and bringing them back to life."

Erie's library is right on the waterfront, not far from where Oliver Hazard Perry built his fleet that defeated the British on the lake in 1813. Ray, who works in the Cleveland aquarium's shark tank, has scuba dived to examine shipwrecks in the lake.

In the library's second-floor Heritage Room, which features paintings of Civil War battles, cabinets of microfilm, and shelves of obscure books, we scanned through the Erie Times-News archive at side-by-side terminals. The resource had been digitized but wasn't accessible outside of this room. Ray had a good idea of where to begin. About a half hour in, he turned to me.

"Oh, look at this," Ray exclaimed. "This is beautiful."

Last October, Simkus was fed up with the defeatist attitude from some in the baseball research community. He took to Twitter to air grievances with what he called a "stigma" attached to Negro League statistics.

"It goes something like this," Simkus wrote. "'The Negro leagues didn't have a centralized stat bureau, the box scores are missing, and the ones we DO have are riddled with problems. So it's too bad but we'll never know what (these) guys did and we'll just have to stick with the tall tales, folklore and hyperbole.' This is no longer true."

It was no longer true because of the efforts of Simkus and his fellow researchers at Seamheads, building on generations of work before their own.

"WE HAVE MOST OF THE BOX SCORES," he emphasized in the thread.

It varies by decade. The 1920s are almost complete. Simkus believes they know of almost all the games played in that decade and have 90% of the box scores. They're missing only 10 games from 1929. But newspaper coverage of the leagues fell off in the 1940s. Still, he thinks they know of 75-80% of the games played in the 1940s, and have "more than half" of the box scores.

Simkus is confident this is true by reconstructing teams' schedules, learning their travel patterns, and cross-checking schedules with that of white semi-pro teams they often played. They've put together most of the puzzle. They've done it all as an unpaid project.

"We're either idiots or doing the right thing," Simkus told me.

Two months after Simkus' Twitter thread, baseball commissioner Rob Manfred announced MLB would give seven Negro Leagues major-league status. Negro Leagues Baseball Museum president Bob Kendrick told me he believes interest in the Negro Leagues is at the highest level of his 28-year tenure with the museum. He said Seamheads played a pivotal role in MLB’s decision, which he says "captivated hearts and imaginations" of the baseball world.

"It took a tireless effort in helping pull these numbers together in such a quantifiable way that would lead us to the announcement in December," Kendrick said. "I’m not going to say it was like finding a needle in a haystack but it damn near was."

Simkus is from a baseball family. His grandfather was a semi-pro player who played against the Cuban Stars in the 1930s. His grandmother saw Hack Wilson play at Wrigley Field. Obsessed with baseball history since he was a kid, Simkus often went to the local branch of the Chicago Public Library to check out "The Baseball Encyclopedia," the 2,000-page holy grail of baseball statistics first published in 1969 and updated periodically until the internet made it unnecessary. During one of those trips, he stumbled upon Robert Peterson's book, "Only the Ball was White," a pioneering work in documenting the Negro Leagues.

"You are talking about some of the greatest players in the first half of the 20th century, and we don't know shit about them," said Simkus, who considers himself part of the third generation of researchers.

His interest became more serious in the early 2000s; he said he needed a "fix" after quitting beer-league softball in his early 30s. He'd pieced together a collection of most of the Chicago American Giants box scores by pouring over library microfilm. In 2005, he pitched to Strat-o-Matic, the baseball board game, the idea of researching and creating a Negro League card set. They initially declined, but in 2008 called him back.

He asked for 18 months to build a full set. He thought he could get enough box scores, but it was a guess more than an estimate. The effort became an obsession. In 2008 and 2009, while working second-shift hours as a dispatcher for a limousine service, he began "double-dipping" as he says. Alone in the office by himself for several hours each night, he researched.

"I would jump on the computer for a couple hours and log into one of the newspaper sites and start printing stuff out," he said.

The Strat-o-Matic set was enough of a hit that he gained something of a following in baseball research circles and launched a newsletter that eventually gained subscribers like Kevin Johnson and Mike Lynch, who ran and contributed to Seamheads.com. The trio later teamed up with Gary Ashwill, who Simkus dubbed "the Michael Jordan of researchers." They also worked closely with historian and Negro Leagues Baseball Museum co-founder Larry Lester. That was the start of their team effort to reconstruct history.

On his own dime, Simkus traveled to Memphis and Nashville in search of box scores. He paid for inter-library loans of microfilm to be shipped to Chicago. He'd have access to the film for a few days and would practically live downtown at the library.

Simkus felt like the Indiana Jones of baseball box scores. He still gets a thrill from unearthing documents. When he finds a new box score or game data, he records the dates, stats, and other information in a Microsoft Excel file and sends it off to Ashwill, the point man, who lives in Durham, North Carolina.

"This is history. We are rebuilding it. Now it matters," Simkus said.

But the work isn't done. There are more box scores to be found. The last mile of the search is the most challenging. The major city daily newspapers have been mostly mined, along with the major African American newspapers of the day, like the Chicago Defender. They have to branch out to smaller cities whose newspaper data is not always accessible remotely - if it exists at all. On Neyer's podcast, Simkus asked for help.

On the drive to Erie, I asked Ray if there was much fear among researchers about losing newspapers that haven't been digitized to fire, water damage, or some sort of human error. Ray said he recently read "The Library Book," Susan Orlean's account of a massive fire at the Los Angeles Library in 1986 that consumed 400,000 books.

"She had a whole chapter about library destruction going back to Alexandria in Egypt, and World War II, and how many libraries have been destroyed over time and all the resources that have been lost." Ray said. "Not baseball box scores, but 13th century documents that were in these libraries that got torched or bombed."

This hunt for history was something of a slow-motion race against time. The Seamheads group accepts they won't find everything, but they want as complete a record as possible. Ray guessed that perhaps no one had looked for these box scores in the Erie Times-News since the day they were published.

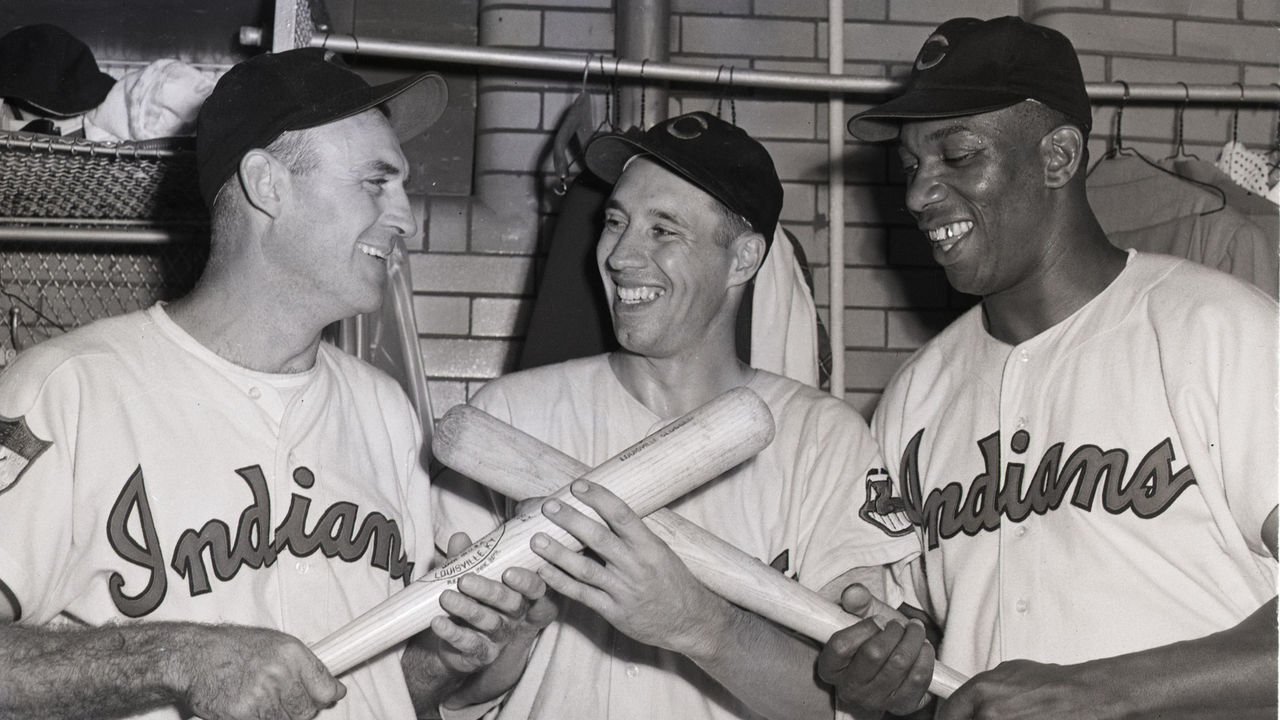

Ray's first find on our trip was a game story and readable box score from a Cleveland Buckeyes-Memphis Red Sox meeting in Erie on Aug. 12, 1946. Luke Easter played in the game, a strikingly large left-handed slugger who Simkus estimates would have hit 500 home runs if he played a full career in the majors. He's one of those players who isn't in the Hall of Fame likely because he didn't arrive to the majors until age 33. His career was split between two worlds.

The wider world only got a look at him past his peak and he still mashed, hitting 31 home runs with a 142 OPS+ as a 36-year-old for the Cleveland Indians in 1952. Johnson is the advanced stats guy within their Seamheads group, Simkus says. He's working on ballpark factors at the moment. It's a challenge.

I happened upon a 1930 game in which Oscar Charleston and the Homestead Grays played against a local white semi-pro team, the Shop Leaguers, which I turned into a PDF and forwarded to Simkus. They want everything, but this was not an item destined to be part of the MLB record.

Ray was mostly focused on the Buckeyes, who often played in Erie. I turned my attention to the Grays, who were based part of the year in nearby Pittsburgh. I entered key words like "Grays" and "Josh Gibson" and specific years. My queries failed to yield much of anything in the 1930s. There was a Grays versus Newark Eagles game with no box score in 1936. But as I made my way into the 1940s, more hits came up. Then I found it. A headline:

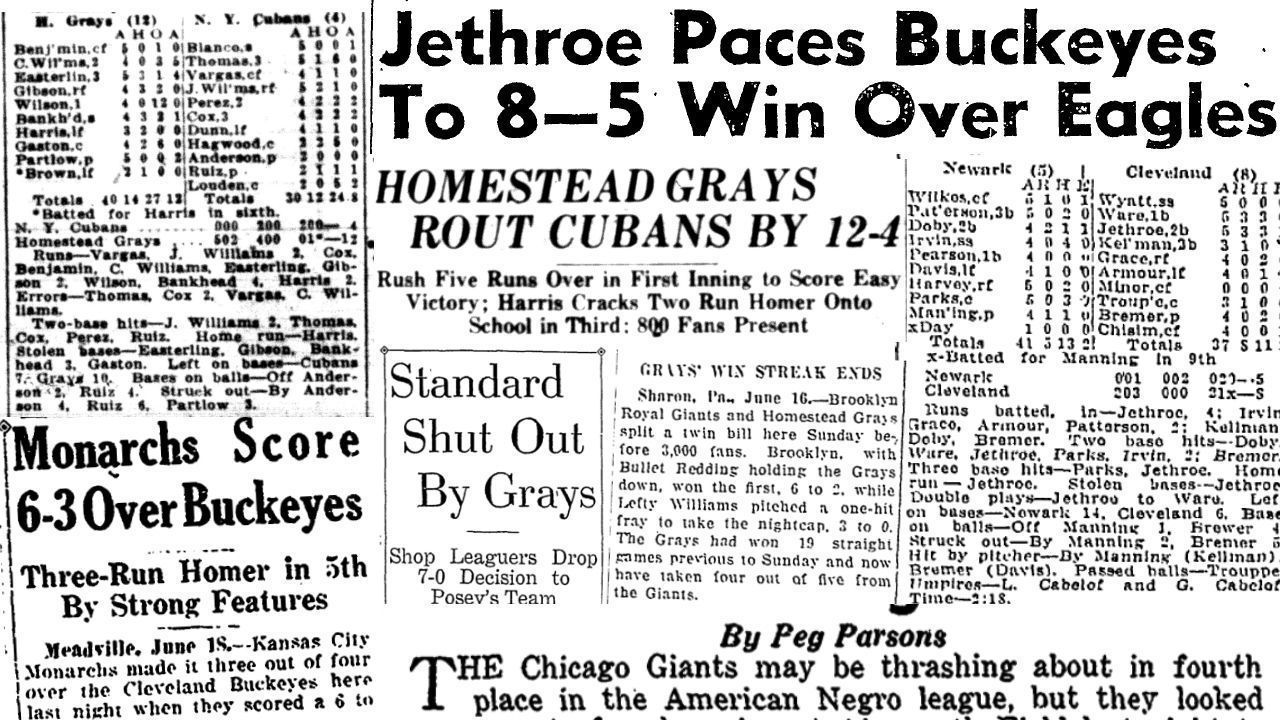

Homestead Grays Rout Cubans By 12-4

"Ray, I think I got something."

I started reading the game story. "In a lusty contest punctuated by 26 base hits, the Homestead Grays defeated the New York Cubans … A crowd of about 800 took in the spectacle." These teams were Negro National League rivals in 1942.

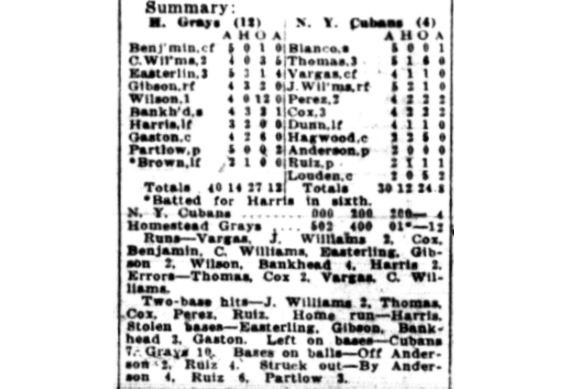

The box score was blurry, though I could make out the surname "Gibson." My heart rate picked up. I couldn't quite make out his stat line - the print was rendered choppy by the digitization.

This is a common research problem. There are some unreadable old newspapers. Game stories with incomplete box scores. Game stories with no box scores. The hope is by cross-checking with another newspaper, often in another city, a complete record can be cobbled together. In his last visit, Ray surprised Simkus by finding a complete box score in the Erie paper from a game played in Niagara Falls, New York. Simkus had seen the game story from the Niagara Falls paper, but it had no box score. The record keeping was imperfect and messy, not any different from the process of collecting 19th century and early 20th century data on the white major leagues.

I had to find the microfilm and get a cleaner look at the box score. With the help of Debbi, a friendly gray-haired librarian, I was scrolling through 1942 Erie Times-News microfilm. But I kept stopping at the front pages, drawn in by war headlines of submarines sinking Allied shipping boats, of the Nazis pushing toward Stalingrad, an explosion killing 20 at a U.S. munitions plant. Ray warned me about this on the drive.

"It helps to go straight to the games otherwise you are going to read about World War II battles," he said.

On Page 20, it was there. Gibson went 3-for-4. What I thought were runs on the digitized version were listed as outs. He also stole a base and scored two runs.

Simkus believes this find will be included in Gibson's major-league record. The Seamheads data is reviewed by MLB, the Elias Sports Bureau, and other historians before being officially accepted. Simkus says updates will likely occur every six to eight weeks. If this is added to Gibson's record, his batting average will jump from .327 to .337 in 1942.

Gibson's great-grandson, Sean Gibson, told the Chicago Tribune this week that one of the stat updates that most pleases him is seeing Josh Gibson's 1943 batting average, which improved to .466 with Baseball-Reference.com importing the Seamheads data.

"At one point it was .441," Sean Gibson said. "That was exciting to see it went up even higher."

The MLB single-season batting average record is now held by Tetelo Vargas, who hit .471 in 1943 for the New York Cubans. Move over, Napoleon Lajoie.

"The work is not going to be done when the data is posted," Simkus said of the Baseball Reference acceptance and uploading of the new data. "Whatever Josh Gibson's stats are when it (went live this week), you have to kinda treat him like Mike Trout or (Shohei) Ohtani. The stats are going to keep growing as we add games and find more stuff. We have accepted that's the reality."

The search is sometimes exciting but more often frustrating. We sometimes found an advance story for a game that was supposed to be played on a certain day, only to go to that day's paper and never find the box score. In one case, Ray found a story several days later explaining the team bus broke down.

"Sometimes they were rained out and they didn't note it, or a bus breaks down. Or sometimes the Black teams would just kind of bail on a date and go play somewhere else. They might have a better offer," Simkus said. "They were trying to survive. …

"A lot of times they would have to violate what we think are best practices for running a business. They desperately needed money. They were always on the cusp of financial ruin. You were waiting for the next day. You were hoping for good weather. You were hoping to get 5,000 people out there so they could keep on keeping on with the season."

The Negro League clubs also played in some unusual places, even smaller towns than Erie, which has about 100,000 people.

"So why are they playing in Erie?" I asked Ray.

We're used to the rhythm of today's American and National League schedules: homestands and road trips but games always played in the same stadiums. Back then, Negro National and American League clubs were always on the move. For example, Simkus said in 1943 the 12 NNL and NAL teams played each other in 71 different cities and towns.

"They rarely ever played in the same city two consecutive nights with the exception of the weekend," Simkus said.

They played in their home city if the white major-league team was out of town during the weekend, but Simkus said they lacked a broad enough fan base to consistently fill a ballpark for a homestand. So they traveled, drawing crowds where they could. That included Erie as a frequent stop.

Ernest Wright, the owner of the Cleveland Buckeyes, also owned the Pope Hotel and its jazz lounge in Erie, Ray explained. To help fill his hotel and club, he would often bring his Buckeyes to town and entice other teams like the Grays, New York Cubans, and Newark Eagles to meet them.

Today, Erie's a depressed city. Sprawl weakened the urban core, which was a lively place in the 1940s because it was a major Great Lakes port for coal, iron, and grain. The port's traffic peaked in 1942. The Pope Hotel no longer stands, torn down in 1978 and replaced by a corrugated metal warehouse. But in its heyday, it was a jazz hotbed. Musicians often traveled similar circuits to the Negro League players, and many stars performed at the Pope.

Aretha Franklin, Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, and Ray Charles all played there, according to the Erie Reader. In his autobiography, Negro League player and baseball ambassador Buck O'Neil fondly recalled befriending jazz legends in Kansas City.

The Pope Hotel was a popular place in part because of the jazz, and in part because it was a safe place for African Americans in segregated Erie. It was one of four businesses designated as free from discrimination according to the "Negro Motorist Green Book," a popular travel guide used at the time by African Americans to help navigate the country.

Erie was also located along a common travel route for clubs. After games in Cleveland, teams would go east along U.S. Route 20 to Erie, then head off to Buffalo and Niagara Falls and into Ontario and back. It was also a manageable drive from Erie to Pittsburgh, New York, and Washington, D.C.

Erie became a common stop for many teams because of its location, Wright, and the Pope Hotel. Erie's what Simkus calls a research "honeyhole" because of the volume of Negro League games played in a city of its size.

Simkus asked Ray to go out to Ainsworth Field, where the majority of Negro League games were played in Erie, to see if there were any artifacts worth collecting for the Negro League Museum. We also wanted to go simply to see it, and to get a sense of how far rumored batting-practice home runs Gibson hit traveled.

We broke for lunch and then made our way to the stadium a few miles away from the library. The longtime minor-league facility opened in 1914 and is situated in a neighborhood of Craftsman-style bungalows. The main, single-level grandstand is still standing, but its main gate was locked. We circled the perimeter of the field and found a gap in the center field chain-link gate and trespassed onto the field.

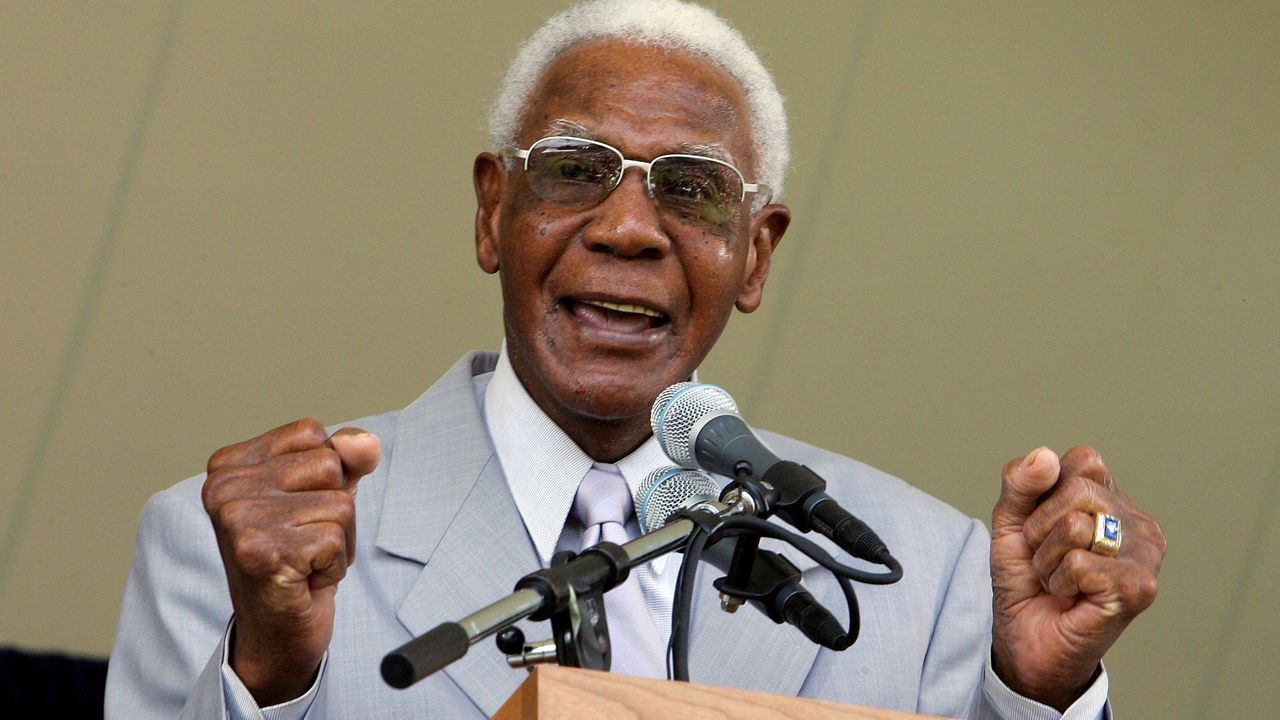

The grandstand was renovated in 2004, but paint is peeling in the rafters. In the old bunker-like dugouts, concrete had broken away and rusty rebar was exposed. In the upper reaches of the grandstand were two painted portraits, one of Babe Ruth, who played here, and one of Sam Jethroe, Erie's baseball legend. Simkus is sure Jethroe would be a Hall of Famer had he played his career entirely in either the Negro Leagues or white major leagues. He didn't enter the majors until his age-33 season with the Boston Braves and led the NL in steals in his first two seasons, posting a 125 OPS+ in his age-34 season. He's a forgotten player everywhere but here.

Kendrick, though, suspects the Seamheads' effort may reopen some Hall of Fame cases that were considered closed.

Rachel Jethroe, Sam's granddaughter, spoke to the Times-News last December, 70 years after Jethroe's exploits were recorded in that very newspaper.

"It's been a long time coming," she said of inclusion in the MLB record books. "These athletes finally get a chance to be recognized."

The distance down the right-field line is only 287 feet, as it's been for more than a century. There was once a school behind the right-field fence, but it was recently demolished. A number of stars peppered it with home runs both in games and in batting practice. Simkus wanted Ray to see if he could find a loose artifact that might represent something of significance. We took some photographs of our surroundings. Ray collected some half-buried bricks from just inside the outfield fence.

Simkus also sent Ray an email asking if he could track down information on a couple of long home runs he read about Gibson hitting here. In doing some digging at the library that morning, it seemed Gibson hit them in batting practice, not a game, in July 1942. According to the Times-News account, they landed on the tennis courts "on the fly" behind left field. The overgrown tennis courts still exist. We estimated it was 400 feet to reach the front fence of the tennis courts. Maybe his shots were 450 feet?

Back at the library after our field trip, I found another Homestead Grays box score, this one a game versus the Buckeyes in 1947. Jethroe and Easter played in it. But Gibson didn't; he died in January of that year at 35.

Gibson had a difficult life. His first wife died during childbirth. He battled alcoholism. I found a story in 1944 detailing his hospitalization due to what the newspaper described as a "nervous breakdown." Gibson led the Black major leagues in home runs 11 times in his 13 seasons according to the new data unveiled this week, and posted a career OPS+ of 215, better than Babe Ruth's 206. Gibson never got a chance to play in the majors; baseball's color barrier didn't fall until the year he died.

"I think with the Negro Leagues, people wanted to find reasons to discount what these unsung baseball hereoes were able to accomplish. There was always an air of skepticism," Kendrick said. "The numbers are there now, for those who needed them to say, 'Well, OK, maybe these guys are as good as old Bob has said they were.' But the numbers will never tell the true story of the Negro Leagues. They just won't. For me, it is about context. I don't want the legend of these athletes to ever die."

For some time, MLB official historian John Thorn didn't believe Negro League records should be considered major-league statistics. Not because of the quality of players but because of how irregular the schedule and record keeping was. He said as much at the SABR convention two years ago in San Diego.

"I approached the subject formally," Thorn told me. "The criterion that established demoting the National Association was the very same one that would eliminate consideration of the Negro Leagues. That was my off-the-cuff response, which I have come to reverse."

In the late 1960s, MLB's Special Baseball Records Committee convened to determine what ought to be considered "major league" in regard to record keeping. The all-white group settled on six leagues, and didn't include any Negro Leagues. Thorn said Black leagues didn't even come up in conversation. The committee also decided to exclude the white National Association of the 19th century due to its "erratic schedule" and "poor newspaper coverage."

Negro League teams might have played well in excess of 162 games per year, but many of those games were against semi-pro and lower-level competition. They played between 40 to 80 games each year against teams of their true peers. The better teams played more major league-level games. While there were standings, an All-Star Game in Chicago, and a World Series, the schedule was nothing like the white game. It couldn't be.

Thorn, who's friends with the Seamheads group members, and who's an advisor to MLB on the issue of Negro League record inclusion, came to reverse his own viewpoint "180 degrees" last year.

"I realized the Negro League's deficiencies, perceived deficiencies, scheduling irregularity ... were all the product of exclusionary practices by major leagues," Thorn said. "We are smarter now than we were then (the 1969 committee). We are more empathic now than when we were then. … If the records are not complete then that's OK with me. My view of history is, just because you put something on a plaque doesn't mean it's so. It doesn't mean it's inert. Hall of Fame plaques have a million errors on them. … But the plaques have a place in history because that's what was believed at the time.

"Is history subject to constant revision based on better information that is substantiated? Of course."

When MLB decided to not place asterisks on last year's shortened-season statistics and champion, Thorn reasoned there was no plausible reason to not consider Negro League statistics as part of the official record of the game.

"It really brought the whole conundrum in front of our faces. If a major-league season could be accepted at 60 regular-season games … then why couldn't we accept shortened seasons for Negro League clubs?" Thorn said. "I think the Seamheads' approach is correct that looking at the Negro Leagues as if they were the white American League and white National League is the wrong place to start.

"History is what it is or what it was. It is not what we think it ought to have been."

The shortened MLB season was also played out during a time of social unrest driven by Black voices, which Kendrick believes played a role in the decision.

Thorn has spoken with descendants of Negro League players. He said they take immense pride in knowing their fathers, grandfathers, and great-grandfathers are now included in the official record book. It's even more important, he suspects, for those families without Hall of Fame ties.

"This is not about them," Thorn said of the 35 Hall of Famers. "This is about the cup-of-coffee types, the one-year regulars. This is about ensuring that the families of these long-gone players can point to the record book and say, 'My great-grandfather was a major leaguer.'"

After a few more hours, Ray and I packed our bags and traveled back to Cleveland. On the ride, Ray noted he was one of the younger researchers. He laughed at that because he's not that young - he's 41.

I asked Simkus later how many volunteers he had working for him. I figured he had quite a few. Six, he said, including Ray. Six.

"You think our sons are going to pick this up one day?," Ray asked me of our six-year-olds.

I had my doubts. We didn't talk as much on our return trip. Ray played the Neyer podcast with Simkus, the one that inspired him to join the mission. Most of the players are gone now, and it's up to their modern-day allies to tell the complete story. Ray will likely make more trips to Erie. There was more to discover. He was also planning a trip to Meadville, which is about 40 miles south of Erie. There's a Gibson four-homer game that happened in Zanesville, but the box score is missing.

There's more to find before the history - and the people interested in finding it - are gone.

Top image credits: Photos of Sam Jethroe, Satchel Paige, Josh Gibson, Luke Easter, and Cool Papa Bell (from left) via Getty Images. Photos of Erie's Ainsworth Field from Travis Sawchik. Newspaper headlines from the Library of Congress's Chronicling America collection.

Travis Sawchik is theScore's senior baseball writer.