Kyle Pitts is a unicorn among tight ends and a problem for defenses

Kyle Pitts is a matchup problem. Steve Devlin said this over the phone not once but numerous times, and who could fault him for repeating himself? Devlin coached Pitts in high school, when the athlete who's vowed to become football's best tight end habitually destroyed opposing schemes and dreams all over the field.

That included on defense. Back at Archbishop Wood High School near Philadelphia, Pitts did double duty as a nimble defensive end capable of darting around the edge, blowing up the run game, or backpedaling into coverage as his unit required. Devlin loved the results. There was the 2016 city playoff game that Pitts broke open by forcing a fumble and tipping an interception, both of which were returned for scores. In his senior finale in 2017, Pitts snared two picks and a receiving touchdown as Wood romped to a 5A state championship.

To dismiss Pitts' defensive achievements as he gets set to enter the NFL - it's not like he'll line up at DE on Sundays - risks missing the point. At 6-foot-6 and 245 pounds, his unicorn blend of speed, smarts, dependable hands, and quicksilver elusiveness helped him torment SEC foes at Florida. Even among pros, he projects as special, a force to fear, and a dilemma to solve on any snap that involves him.

"Sure, the NFL's the best of the best. You've got guys who can run and cover," Devlin said. "But Kyle brings a different dimension to the game."

When the NFL draft starts April 29, it's possible that a handful of quarterbacks are the only guys selected before Pitts, one of the top pass-catchers in the class and its most dynamic prospect, full stop. Linebackers can't keep pace with a player who runs the 40 in 4.44 seconds. Defensive backs with equivalent wheels get outjumped or outmuscled downfield.

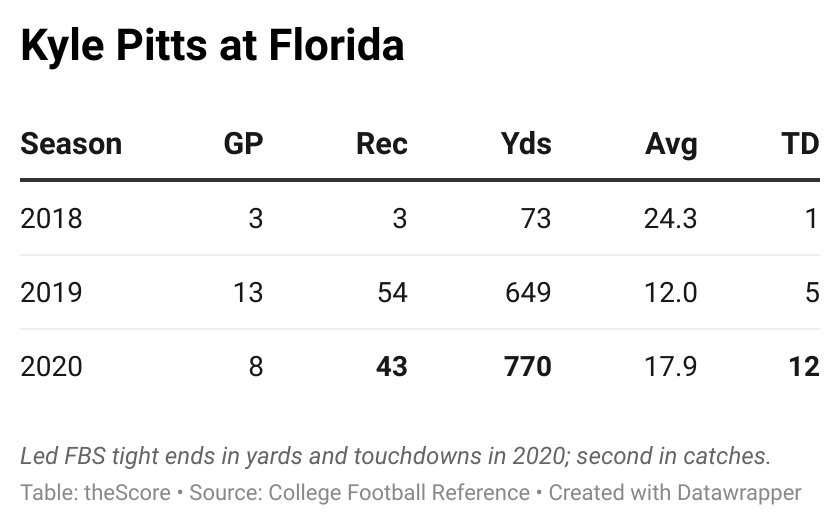

Pitts cracked the top 10 of Heisman Trophy voting in 2020, a first for his position in 43 years. His timing was impeccable. By turning pro at 20, he'll have plenty of runway to try to redefine what it means to play tight end, joining Darren Waller and few others as featured threats of towering size whose fleetness of foot has no NFL precedent.

When Pitts' boosters talk about him, superlatives roll off the tongue. Devlin said Pitts has the strongest hands he's seen. Gators tight end coach Tim Brewster - Antonio Gates' first NFL position coach - has called him a generational talent, raving to The New York Post that Pitts turns 50-50 balls into 90-10 propositions. "He is the definition of a mismatch player," NFL Network analyst Daniel Jeremiah wrote about Pitts in March, when he rated him the second-best player in the draft after Clemson QB Trevor Lawrence.

"I don't care if you're a safety. I don't care if you're a linebacker. I don't care if you're a cornerback," retired receiver Nate Burleson said on NFL Network's "Good Morning Football" show last month, teeing up a frank quip: "You are up Pitts creek if you're trying to guard this dude tight."

Kyle Pitts has a longer wingspan than any WR or TE in the NFL (83 3/8") in the last 20 years 🤯

— PFF (@PFF) March 31, 2021

Breaking DK Metcalf’s record 👀 pic.twitter.com/CTt8U0sEMT

In 2018, ahead of his freshman year at Florida, Pitts told The Palm Beach Post a positional origin story that strains belief now that he's about to be drafted high. Tight end was always his preferred role, but an early high school coach - this was before he played for Devlin at Archbishop Wood - refused to deploy him there, deeming his three-point stance irreversibly deficient.

Safe to say this take aged poorly. Recognizing the attention Pitts commanded in all situations, Devlin stationed him everywhere across the line of scrimmage in Wood's spread offense: as an attached tight end, in the slot, out wide, as the lone receiving option on the weak side. Florida harnessed his versatility, too, empowering him to become QB Kyle Trask's most explosive regular target. Pitts overmatched SEC secondaries as a sophomore and junior, and he did that in a range of ways.

Take Florida's season opener against Ole Miss last Sept. 26. Pitts caught eight balls for 170 yards in a 51-35 win, personally accounting for four of the Gators' six TDs. On two of those plays, he shook loose of double coverage to snatch Trask's lob to the end zone. On another, he bolted by the linebacker shadowing him, slowed to make the reception, and uncorked a cruel stiff-arm to the dome that cleared his path forward.

Kentucky was comparably helpless on Nov. 28, Pitts' return from a three-week concussion layoff. Three of his five snags against the Wildcats went for TDs, each created when he sidestepped a defender with water-bug agility - once near midfield on a post route and twice on unguardable feints by the goal line.

"He's definitely a nightmare, especially down there in the red zone," said Devlin, who's now the defensive coordinator at Division III Ursinus College. (Coincidentally, Ursinus is the alma mater of Florida head coach Dan Mullen, himself a former college tight end.)

"Defensively," Devlin said, "you only have so many options. He wins those one-on-one battles."

Come draft day, quarterbacks are expected to monopolize the first several choices, which reflects the depth of the QB class and NFL teams' desperation at the position. Pitts' stock doesn't lag theirs by much: theScore's latest mock has the Cincinnati Bengals taking him fifth overall, the first non-QB off the board.

Such an outcome would elevate him above this class' consensus top receivers, each of them a fellow SEC star - LSU's Ja'Marr Chase and Alabama's DeVonta Smith and Jaylen Waddle - and it would counter well-worn historical trends. Mike Ditka (Chicago Bears, 1961) and Riley Odoms (Denver Broncos, 1972) are the only NFL tight ends who've been drafted No. 5, and none have gone sooner. T.J. Hockenson, Eric Ebron, Vernon Davis, and Kellen Winslow Jr. stand alone at the position as top-10 picks this century.

The thought is that Pitts has more in common with Waller (the 204th pick in 2015), Travis Kelce (63rd in 2013), and Rob Gronkowski (42nd in 2010), prospects of lesser shine who set the gold standard for tight-end play.

Charting the position's strategic and aesthetic evolution means contrasting Ditka, a Hall of Famer with one career 1,000-yard season, with Kelce, the No. 1 pass-catcher on consecutive AFC title squads who was deployed in the slot or out wide on 63% of pass snaps in 2020, per PFF. Meanwhile, the 6-foot-6, 255-pound Waller reeled in 107 passes last season - more than Gronkowski, Gates, and Tony Gonzalez ever caught - by burning, skying above, and wrongfooting defenders on the run. It means taking seriously the potential that Pitts sees in himself.

I will be the best when it’s all said and done..

— Kyle Pitts👑 (@kylepitts__) March 6, 2021

"It's going to come with consistency over the years," Pitts told reporters at Florida's pro day, explaining how he plans to pursue GOAT status. He added, "Being able to do things that other tight ends aren't doing will make me special."

Nitpickers worry that Pitts isn't a great blocker, but inasmuch as that matters for a player with his toolkit, Devlin figures he'll grind at the next level to shore up any shortcomings. Among his favorite memories of their time together is the recurrent sight after fall practices of Pitts running routes at Archbishop Wood's unlit field, refusing to let his quarterback go gently into the night. It fell to Devlin to urge him to head home.

Rarely did the coach remove Pitts in big games, rotating him from offensive weapon to defensive force as possession dictated. Pitts unlocked so many possibilities at tight end, be it in play action, for his offense's run game, or when opponents stomached the risk of guarding him one-on-one. An evergreen truth emerged.

"People have to play up to his competition, up to his ability," Devlin said. "No doubt, you throw the ball to him, he's going to come down with it."

Nick Faris is a features writer at theScore.