Frugal MLB owners' complaints about profligate spending won't fix the problem

It's rare to hear Major League Baseball owners criticize each other in public given their opaque world of sealed financial records and rare media availability.

Yet once in a while, the curtain is pulled back on their business and personal animosities.

Last month, Colorado Rockies owner Dick Monfort criticized the San Diego Padres for their spending. The once low-spending Padres have been doling out dollars like a large-market club in the last three years.

"What the Padres are doing, I don't 100% agree with, though I know that our fans probably agree with it," Monfort told the Denver Post's Patrick Saunders. "We'll see how it works out. … It does put a lot of pressure on you."

Monfort's issue is that the Padres are upsetting the traditional order of things. As theScore examined, the Padres and the Texas Rangers are the only teams that were outside the top 10 spenders from 2003-14 to have moved into the top 10 over the last decade. In showing rare upward mobility, the Padres aren't staying in their lane.

"But it's not just the Padres, it's the Mets, it's the Phillies," Monfort said. "This has been an interesting year."

New York Mets owner Steve Cohen, whose personal wealth dwarfs almost every other MLB owner, recently fired back.

"I've heard what everyone else has heard: that they're not happy with me," Cohen said.

"I'm not responsible for how other teams run their clubs," he added. "I'm really not. That's not my job. And there are disparities in baseball. We know that to be true. I'm following the rules. They set the rules down, I'm following them."

The Mets spent more on a couple of players this offseason than the Pittsburgh Pirates ($252 million), Tampa Bay Rays ($281 million), and Oakland Athletics ($337 million) - have spent on free agency in the last 20 years total. The New York Yankees' outlay for Aaron Judge alone also exceeded those totals.

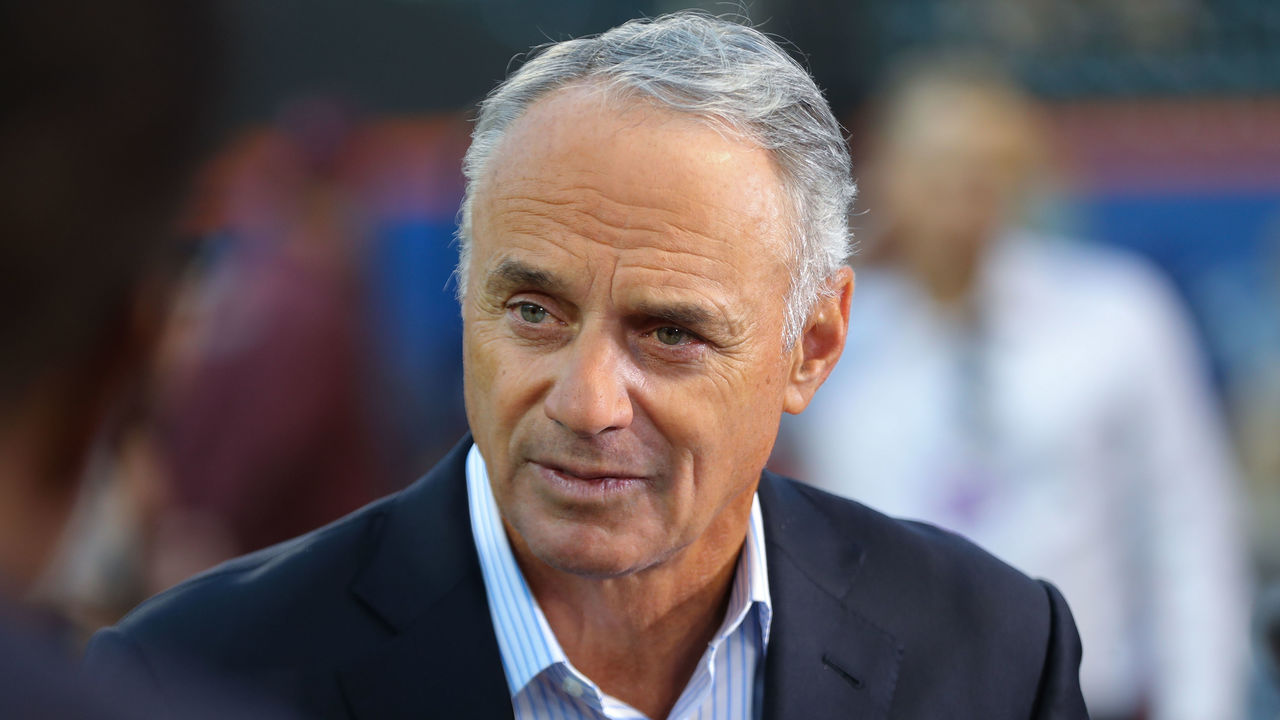

MLB commissioner Rob Manfred chastised the complainers:

Revenue disparity, really important topic in the industry right now. It's not unrelated to the local media issues. … I think people know what happened in the winter. I think that they understand that it happened within the confines of the system they negotiated, and beating your gums about it doesn't accomplish a lot.

Why are so many owners uninterested in spending to compete? Will they ever change? Are some fault lines between owners starting to emerge?

While this was a record offseason for free-agent spending, it was confined to just a few clubs and players, which is typically the case in baseball. The gap between the big and low-end spenders is growing.

Seven clubs combined for $2.8 billion of the free-agent spending, or 77% of all dollars guaranteed. Eight players accounted for 54% of dollars guaranteed.

The biggest issue sapping incentive to compete is guaranteed checks. While there were changes to the new collective bargaining agreement designed to curb tanking, the revenue-sharing model remained mostly unchanged.

All teams share centralized revenues equally, like national TV rights deals, MLB Advanced Media digital revenues, and All-Star Game revenues.

But teams also share local-rights revenues.

The process is complicated, but 48% of all local revenue MLB clubs make each year is placed in a pot and split among clubs based on a formula. Clubs that generate more revenue thus end up transferring some of their wealth to low-revenue clubs.

It's estimated that every MLB team is earning at least $100 million in nationally shared revenues, and local media rights, before ever selling a ticket. That saps incentive.

(A players' grievance over how the A's, Miami Marlins, Pirates, and Rays spend those revenue-sharing dollars - or don't - remains unsettled.)

All North American pro sports leagues share revenue in some way or another. But unlike other leagues, there's no cap-and-floor system in baseball forcing every owner to meet a payroll minimum. There is a competitive balance tax in MLB that aims to control spending at the top of the market, but there's no floor to force teams to spend to an agreed minimum level. The players' union is against a hard cap, which would likely be needed to institute a floor.

One business practice that seems lost among some owners is the idea that improving their product will yield more ticket buyers.

The Padres' spending in recent years is paying off, with more business for the club.

MLB attendance as a whole was down 18% last year compared to its 2007 peak, but the Padres have been one of the few teams to increase attendance recently. They averaged 26,401 fans in 2017, 10th in the NL, but rose to 36,882 last year, fourth in the NL. The only season the Padres have even been at that level was 2004, the year the club opened Petco Park.

Fan enthusiasm has also increased.

What fan fest looked like back in 2015 😳😳😯 #PadresFanFest #PadresTwitter @Padres pic.twitter.com/1oYn0hXs2N

— Xyomara Rodriguez (@Xyomara14) February 5, 2023

A few people have showed up for Padres Fan Fest. pic.twitter.com/VRoJ2Mkmom

— Sammy Levitt (@SammyLev) February 4, 2023

Whole City Behind Us#PadresFanFest pic.twitter.com/KKiYInJY7k

— San Diego Padres (@Padres) February 5, 2023

The Padres are the exception, though.

At the other extreme are the Pirates, whose attendance has been cut in half (15,524 fans per game last campaign) compared to 2015 (30,847 average), which was the last season they made the playoffs.

The club's payroll last year was $20 million less than it was in 2001. But revenue-sharing dollars are enough to keep Pirates owner Bob Nutting content.

A salary floor is a pipe dream at this point, and so too, it seems, are major changes to revenue sharing.

To change behavior, MLB fan bases either need more spenders like Cohen and the Padres' Peter Seidler or a change to incentives. It's not like all of the 724 billionaires in the United States are clamoring to own an MLB team.

While owners have been reluctant to push each other to be more competitive, they might soon receive an external shove.

One possibility for change may come from the financial crisis that's befallen the largest group of regional sports networks.

The live-TV sports world is transitioning from linear cable to streaming, and that's placed Bally Sports, MLB's largest RSN partner, on the doorstep of bankruptcy. U.S. cable subscribers have declined by about 30% from their 2014 peak.

The local TV model is at a breaking point, and the distribution of local live sports TV may be in for a forced overhaul. The guaranteed checks MLB owners have enjoyed since being bundled on cable in the 1980s are in jeopardy.

If MLB owners such as Monfort had to compete for subscribers, to compel fans to buy access to televised games through a direct-to-consumer model like Netflix - or an expanded version of MLB's out-of-market product MLB.TV - incentives would change dramatically.

Having to sell subscriptions instead of relying on guaranteed revenue would increase the incentive to compete, which ought to be good for consumers.

To truly change the way many MLB owners operate, there must be a change to the incentive structure. The best hope for small-market fans might be in how they watch games and how they vote with their wallets. That future might not be too far away.

Travis Sawchik is theScore's senior baseball writer.