The NBA doesn't need a hard cap. Don't let owners tell you otherwise

By most accounts, the NBA is doing better than ever.

Whether your evaluation is based on the product on the court or the massive dollars it generates, the league appears poised for its own version of the roaring '20s.

Yet some owners may be prepared to jeopardize that momentum in pursuit of a hard salary cap, or as ESPN's Adrian Wojnarowski reported, an "upper spending limit." Sources on the players' side of negotiations, meanwhile, reportedly indicated to Marc Stein that players are willing to face a work stoppage rather than accept a hard cap as part of the next collective bargaining agreement.

The current CBA runs through the 2023-24 season, but the NBA and its players face a Dec. 15 deadline for either side to give notice that it wants to opt out of the agreement a year early. That would mean a new contract would be needed before next season.

It's not difficult to understand why a hard cap is a non-starter for the players' association.

The league's argument for a hard cap, according to Wojnarowski, is that the NBA's current model - where a team like the Warriors can spend more than $370 million on salary and luxury-tax penalties despite the current $123.7-million cap - isn't sustainable.

Good luck trying to sell that to the players or the public.

According to Forbes' annual report for 2022 - published just a day before Wojnarowski's report - the average NBA team valuation skyrocketed 15% in the last year and now stands at $2.86 billion. Even the least valuable NBA team (New Orleans Pelicans) is worth $1.6 billion. Only the Brooklyn Nets lost money last season, with 29 of 30 teams turning profits that ranged from $12 million (Clippers) to $206 million (Warriors).

Those stunning figures may soon be dwarfed. For its next media rights deal, which will come into effect when the 2025-26 season tips off, the NBA is reportedly seeking an agreement worth double or even triple the current deal, which delivers the league nearly $2.7 billion per season.

The league's current soft-cap model allows teams to exceed the salary cap to re-sign and retain their own players. Various exceptions are available to over-the-cap teams based on how far over they are. But if a team exceeds the cap to the point that they spend beyond the tax threshold (which is set at $150.3-million for 2022-23), they pay for it.

Depending on how far over the threshold a team is, and whether it qualifies as a repeat tax offender (by spending into the tax in at least three of the previous four seasons), tax teams can pay anywhere from $1.50 to $4.75 for every $1 spent above the threshold. The NBA then redistributes that tax money as a means of revenue sharing. For 2022-23, 10 tax teams are projected to contribute nearly $700 million to be dispersed among 20 non-taxpaying clubs.

In addition to eliminating the revenue-sharing benefits of the current tax system, a hard cap could backfire by punishing the best-run organizations. Without the ability to exceed the cap to retain its own players, a team that scouts, drafts, and develops well would eventually lose homegrown stars because the NBA itself would prevent the franchise from paying all of them fair market value.

Then again, perhaps that's music to some owners' ears, as it provides another excuse for frugality.

When the Thunder balked at paying James Harden the max back in 2012 because it would've made them a tax-paying team, critics lambasted Oklahoma City's ownership group, which is collectively worth billions. The Thunder eventually traded Harden to the Houston Rockets.

A hard cap gives similar-minded owners an easy out. It incentivizes low-ball offers and team-friendly contracts. It reinforces the narrative that the burden of sacrificing for the greater good should fall on the players rather than on the owners, who could just spend more to keep teams together.

A key plank of the owners' argument, as reported by Wojnarowski, is that the current model fails to encourage consistent competitive balance throughout the league. However, like any assertion that the current system is financially unsustainable, the competitive balance theory doesn't hold up under scrutiny.

In theory, a hard spending limit could help foster competitive balance. But in reality, the NBA has already achieved an admirable level of parity.

Whether using betting figures, projection systems, or the eye test, the Association entered the 2022-23 season more balanced than ever, with an unprecedentedly wide-open title race. More than half of the league's teams tipped off the season fancying themselves Finals contenders. How can any professional sports league do better than that? A league of 30 .500-ish squads isn't realistic, and frankly, it wouldn't be all that interesting.

There will always be teams that are closer to contention than others in the ebb and flow of roster-building. There will always be teams that believe sinking to the bottom is the best way forward - a necessary evil as long as the draft lottery exists in its current form.

There will always be owners willing to spend to the absolute limit of whatever system is in place, and those who try to nickel-and-dime their way to success. If a hard cap was installed to absolutely limit how much teams can spend, would the salary floor rise?

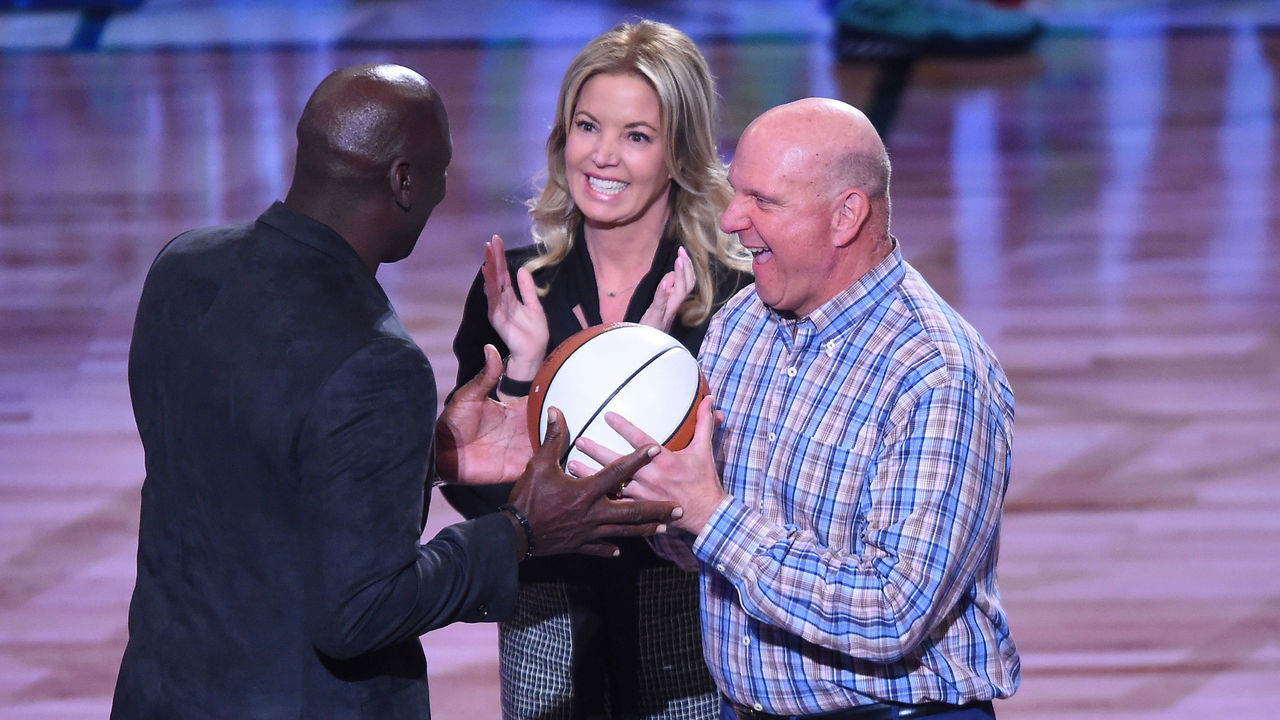

The league's cheapest owners want to hide behind the idea of competitive balance without spending the money necessary for their teams to compete. The Warriors' ability to spend astronomical sums in comparison to small-market teams has been an especially contentious topic over the last year, but it wouldn't be an issue if billionaire owners stopped riding the league's rocket ship of franchise value without spending on the product to merit those values.

It's true that larger markets can generate more revenue for themselves, but that shouldn't matter in a league where the smallest-market franchises are owned by people worth nearly $19 billion (Memphis) and $5 billion (New Orleans).

If a longtime owner truly feels financially overmatched and out of their league in the new, booming NBA, there is an alternative to whining about it or asking everyone else to play down to their level: They could simply sell their team for a gargantuan return to other billionaires who are more willing to compete with the Warriors of the world.

Joseph Casciaro is theScore's senior content producer.