How to find a ballplayer: Lessons from two of the best scouts of all time

At the Society for American Baseball Research conference in Chicago last summer, I was curious about one particular presentation.

The three-day event featured dozens of speakers and research spread throughout various ballrooms and meeting spaces at the Palmer House Hotel. The talk I was interested in was situated in a remote meeting room on the sixth floor. A sign outside the room read: "Research Committee Meeting: Scouts."

Major League Baseball is a sport with a rich history and obsessive recordkeeping. We know who led the major leagues in batting a century ago. We know who the best teams and players were throughout the game's history.

But one blind spot in the game's record is that we don't know who the best scouts are, the behind-the-scenes personnel who identify talent. We know some of their names and some of their stories, but there are no scouting leaderboards at sites like Baseball Reference, FanGraphs, or Baseball America.

When a team enjoys success tied to its ability to draft and develop prospects, accolades generally go to general managers and club presidents, not the scouts first identifying the talent.

In Chicago, I learned SABR's scouting committee chair Rod Nelson, co-chair Jason Sigler, and his research team from Ohio State University have linked nearly every major-league player since 1950 with the scout who signed them. It's known as the "Who-Signed-Whom database," Nelson said.

Nelson explained why he set out on this project, which consumed countless hours investigating various sources since 2001. He worked with the late Roland Hemond - a two-time MLB Executive of the Year - to send out hundreds of questionnaires to help fill in the blanks.

"The research community has recorded virtually every hit, run, and error that's been tallied for over a century and a half of Major League Baseball, yet there is no authoritative registry of professional baseball scouts as there are for players, managers, coaches, umpires, front office executives, broadcasters, and writers," Nelson said. "These baseball lifers who toil in obscurity with little compensation and a lack of recognition are simply the best damn storytellers one will ever meet. And they do it for the love of the game.

"It dawned on me that I could do something about it."

I immediately had questions upon learning about this new dataset: Who are the most prolific scouts? What are some of their secrets, and timeless lessons? What are some great stories that haven't been told?

theScore was given early access to the data to attempt to answer those questions. It's an important time in scouting's history. Scouts are under pressure from technology. When Statcast first launched in 2015, I heard from scouts terrified about what it meant that new instruments could measure exit velocities, player movement, and pop times, and that data science could unlock hidden trends and tendencies, rendering some of the scouts' observational skills irrelevant. What was to become of their stopwatches, radar guns, and their roles?

According to Baseball America, some teams downsized their scouting departments following the pandemic. In the late 2010s, the Houston Astros disbanded their pro scouting department entirely under former GM Jeffrey Luhnow, rebuilding it only in recent years.

Based on SABR's data, theScore was able to interview the top two living scouts based on the combined WAR totals of players they signed. If there's one underlying element to their stories, it's that the human element still matters.

The rarest of finds

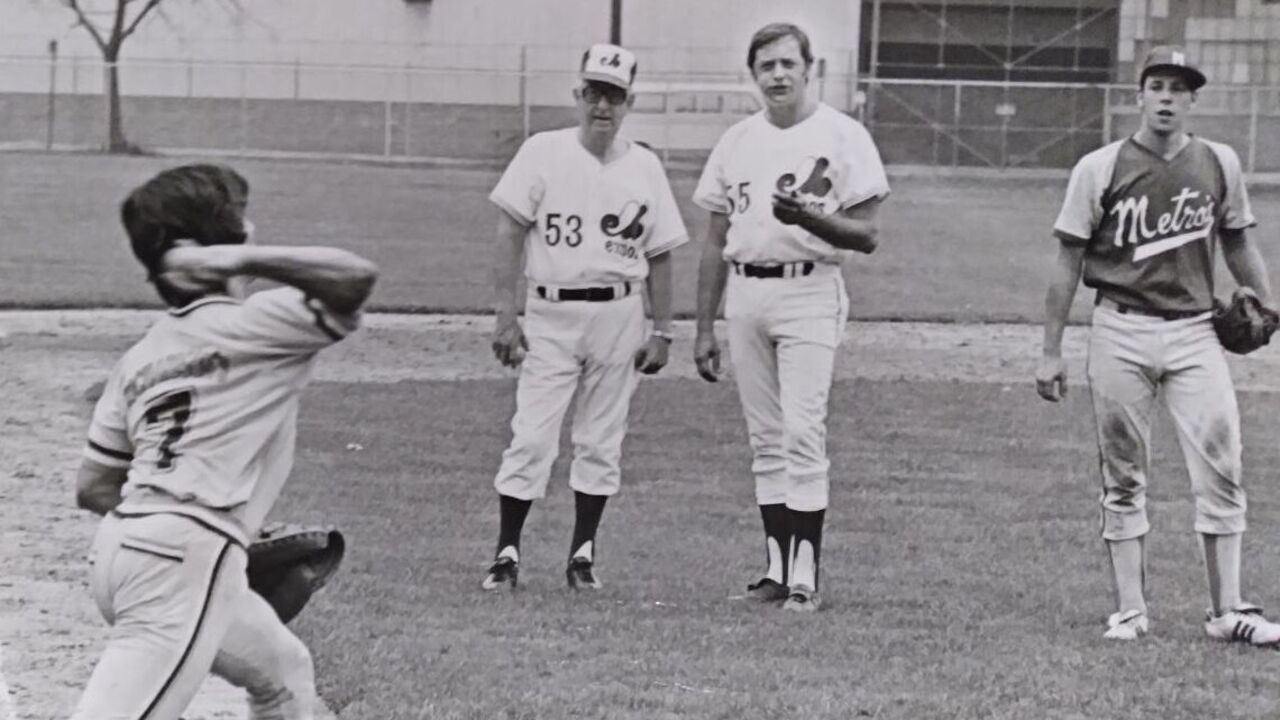

In the late 1970s, Bill MacKenzie filled dual roles with the Montreal Expos. His primary task was working with the organization's catchers, helping players like Hall of Famer Gary Carter refine their talent. But he also scouted for the club.

The Expos often had player development personnel spend time scouting. Today that's rare, as roles are more specialized, and departments are siloed off from each other.

In the 1970s with the Expos, the roles of scouting director and player development director were held by the same individual.

MacKenzie, from Pictou, Nova Scotia, said there were benefits in having a hand in both roles.

Being a hybrid coach-scout meant you knew what positions the club developed well - you saw it and experienced it. You also knew what skills were more difficult to develop.

MacKenzie is the most efficient scout still living - retired or active - in SABR's database. His 10 signees averaged 33.5 WAR in their major-league careers; his average ranks third overall. He also ranks second in total WAR (167.4) signed among former and active scouts who are still living. It ranks 22nd all time.

The dual role helped inform MacKenzie's approach one day in March 1977, when he got the tip of a lifetime.

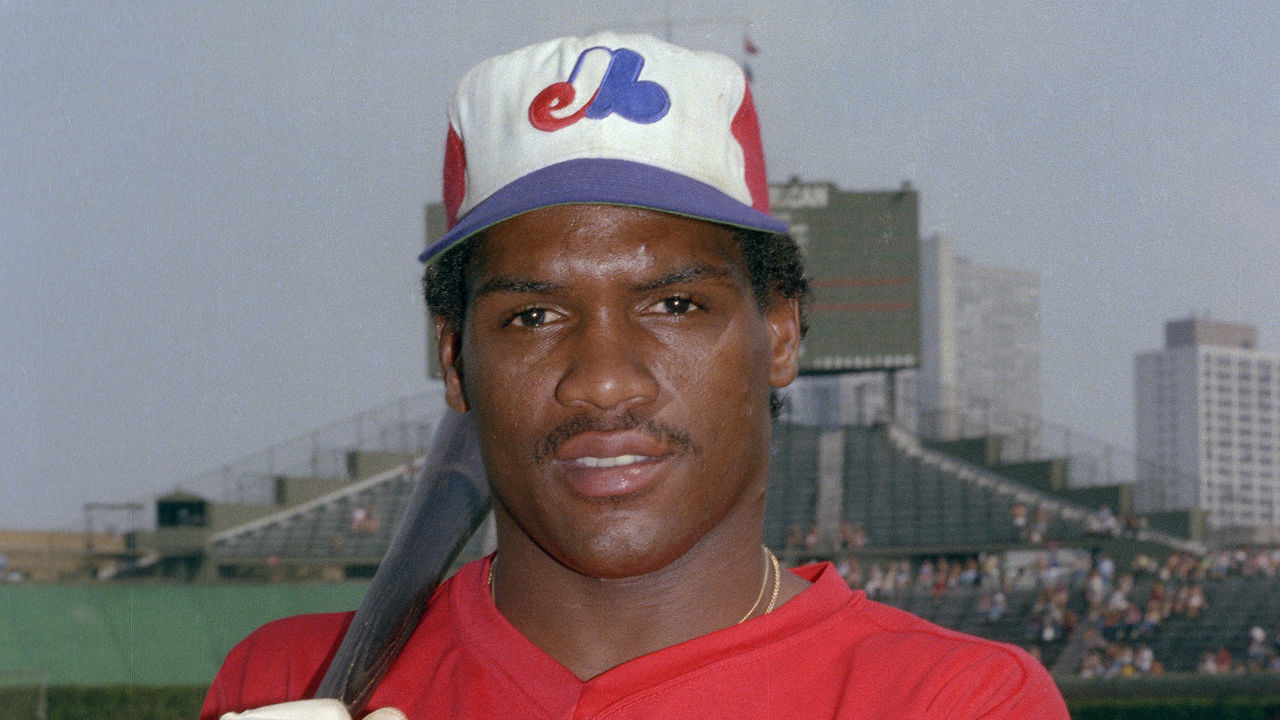

"I got a call, an anonymous call from a lady who asked, 'Does anyone in your organization know anything about Tim Raines?'" MacKenzie recalled. "I said, 'No, we don't have any record of him.'"

This was before Perfect Game, before Baseball America, before social media. Until that point in Raines' senior year, it's possible no one knew of him.

Raines' Seminole High School in Sanford, Florida, was located 40 miles southwest of the Expos' spring training facility in Daytona Beach. MacKenzie was told Raines' team was playing a game nearby later that day.

"He wasn't 'Rock' at the time because he was a skinny little guy," MacKenzie said of his initial impression.

Raines was maybe 5-foot-8 and 150 pounds. He played shortstop, as most of the best athletes do at that level, but it was clear to MacKenzie he lacked the arm to play there.

"He didn't do a whole lot," said MacKenzie, recalling a game played nearly 50 years ago. "Except in his third at-bat. He hit a ball into right-center field. You swore you were seeing Willie Mays run the bases."

The contact was surprisingly loud, too. MacKenzie immediately realized this was rare athleticism and speed. The Expos prized both. The club could add strength and skill, but speed is a skill you can only refine.

After the game, MacKenzie spoke briefly with Raines, hearing he had some football scholarship offers to smaller Division I schools. Raines averaged 10.5 yards per carry as a running back that fall, but the biggest schools believed he was too small.

MacKenzie also learned Raines was young for a senior; he wouldn't turn 18 until the fall, which meant he had even more upside relative to his draft class.

"I just asked him what he planned to do after high school," MacKenzie said. "I told him I was a scout for the Expos. I think he was rather excited by that."

Raines confirmed to MacKenzie that, to his knowledge, no other scouts had seen him play.

"When I came back to camp, I told (scouting and player development director) Mel Didier, 'I think we have to put him on our draft list," MacKenzie said.

MacKenzie never saw Raines play again as an amateur. But what he did do is call Raines' school and speak with his coaches and teachers. The reports on his athletic makeup and his willingness to work were excellent.

MacKenzie also made a trip to the Raines family's modest bungalow in Sanford, where Raines' parents Ned and Florence continued to live long after their son's playing days.

MacKenzie was curious to hear how Florence thought Tim might do navigating the world of professional baseball, including leaving the climate and culture of central Florida for minor-league towns in the Expos system like Quebec City and Jamestown, New York.

"I tried to get to know the family home as much as I could," MacKenzie, now 77, said of his approach to amateur scouting. "You worry about some of these guys: what kind of family life, how good is he going to develop away from home in a strange environment? You do the whole nine yards. You check his schooling, his upbringing, his family.

"His mom was really nice. She wanted what was good for him. If he wanted to go to college to play football, that was his decision. If he wanted to play baseball, that was up to Tim."

He learned that Raines was one of seven children. He was likable, funny, and a worker. Later, when Raines was in the Expos' system, MacKenzie was throwing him extra batting practice one day.

"I must have thrown for about an hour. He was taking his last swing and I hit him in the ass with a pitch," MacKenzie said. "He looked out at me and he said, 'Mac, that's enough."

Back in 1977, when spring training ended and MacKenzie left camp, he asked the club's Florida scout, Bill Adair, to take a look at Raines.

"A few days later he called me back and said, 'I don't like him as a prospect,'" MacKenzie recalled. "I said, 'If that's the case, Billy, I'm going to draft him right out of the office.' So that's what I did."

The 1977 draft was held in early June in New York City. In those days, the selections were made in a hotel lobby or a ballroom downstairs. Clubs were stationed in suites elsewhere in the hotel.

"The whole baseball crew was there. We just sat around a hotel suite with the board up and interchanging names: 'Where do you think this guy would go?'" MacKenzie said. "We had all our scouts available to us to call them in a hurry."

MacKenzie wanted to add Raines, but there was no way of knowing if other evaluators regarded him as highly. The Expos purposely kept his name under wraps in case they were the only ones who knew about his 80-grade speed.

"He might have fallen under the radar. He was a little guy playing shortstop, and he wasn't a shortstop."

The Expos had the second overall pick and chose pitcher Bill Gullickson between Harold Baines going first to the White Sox, and Paul Molitor going third to Milwaukee. Raines was still available in the fifth round, but MacKenzie was becoming restless.

"I convinced (Didier) that we better start considering him pretty soon," MacKenzie said.

Raines was the 106th player drafted that year. Only nine other players from the fifth round made it to the majors.

"Who knows, he might have gone to the seventh, eighth, ninth round," MacKenzie said. "No one knew for sure."

While Raines' speed was apparent, what was more important was what MacKenzie learned about his makeup.

Raines learned to switch hit in the minors, an unheard-of development. He added 30 pounds of muscle. He became 'Rock,' though Raines told Sports Illustrated's Ron Fimrite in 1982 that the nickname came about for a different reason: "There was no way I could catch a ground ball hit right at me. I guess that's how I got the nickname 'Rock.' I got it my rookie year - they say it because of my hands."

The visits, phone calls, and the human intelligence gathering were as important to MacKenzie as anything he saw on the field.

"I would say the No. 1 thing would be makeup," MacKenzie said. "If you have a kid with that kind of makeup, positive attitude, that doesn't get down on himself, that accepts challenges - those are the kids that are successful. There's a lot of kids who have been blessed with great ability but just don't have the desire to prove anyone wrong, or prove they are good enough.

"The Expos organization was really good at that: 'This kid has the skills to play in the big leagues, let's see how bad he wants it.'"

Raines had the willpower to excel to maximize his physical gifts, and enough willpower to recover from a drug habit he picked up early in his major-league career.

That focus on athleticism paired with quality development led to an excellent run for the Expos. The 1982 All-Star Game played in Montreal featured four Expos starters they drafted and developed: pitcher Steve Rogers and three future Hall of Famers in Carter, Raines, and Andre Dawson.

Scouting has changed a lot since those days, of course, but MacKenzie believes the human element will always matter and that it's too often discounted today.

"I never carried a radar gun around with me," MacKenzie said. "I never looked at their stats. I looked at the boy. I broke the boy down. It just concerns me so much today. I don't know what the scouting industry is doing today.

"The analytics are taking over the game, unfortunately."

Trusting the scouting eye

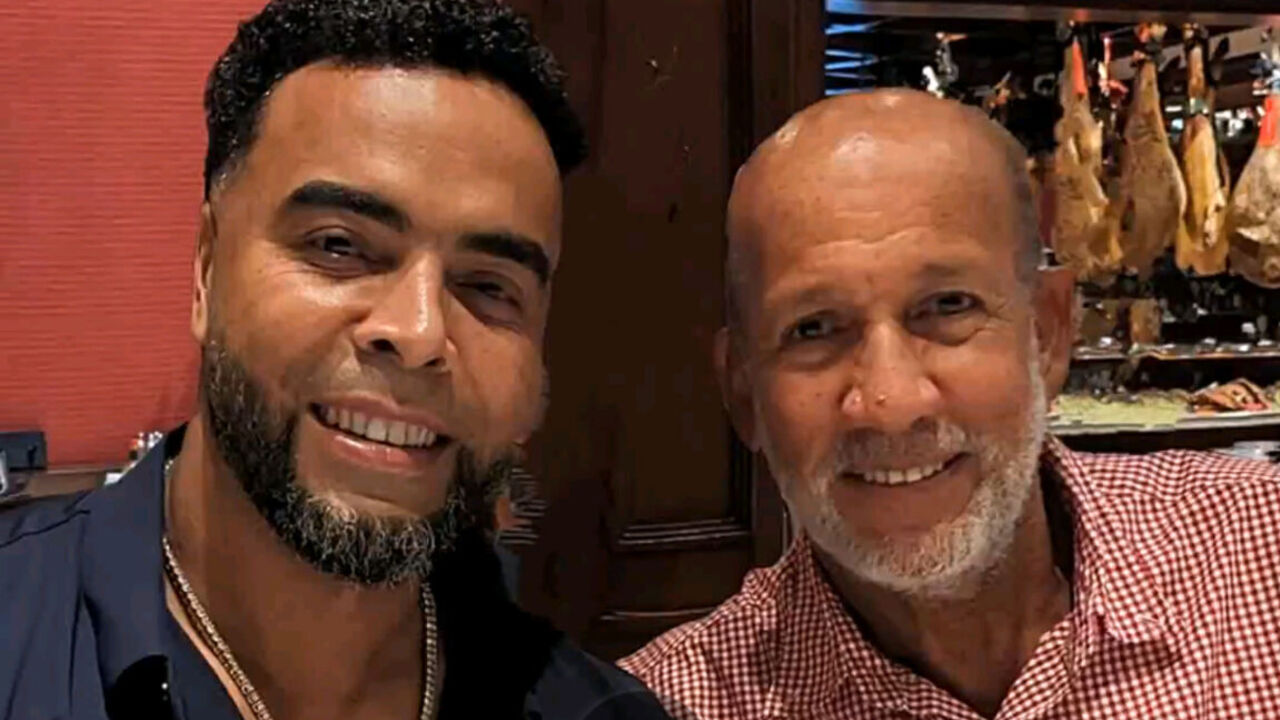

Eddy Toledo is the top living scout in terms of total WAR signed, according to Nelson's database.

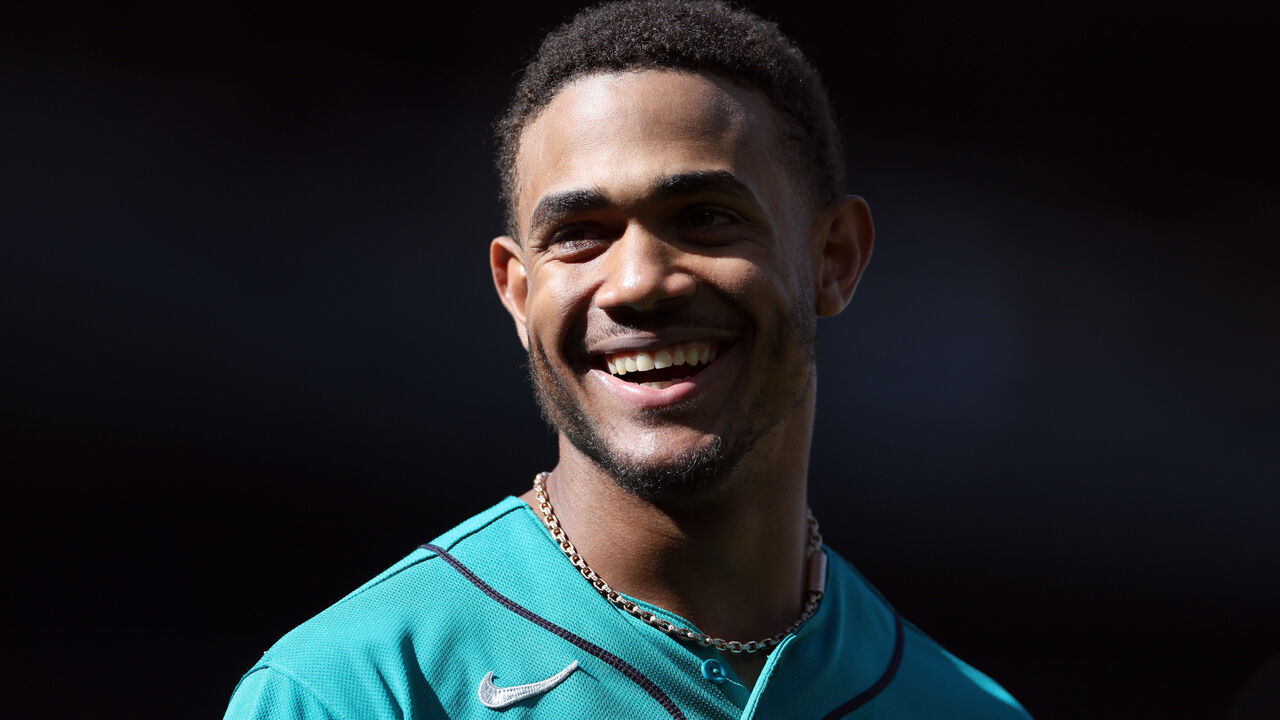

Overall, Toledo ranks 14th in history with 200.7 WAR of players signed, and he'll almost assuredly rise in the rankings as Julio Rodríguez plays deeper into his career.

Dominican stars Nelson Cruz, José Reyes, and Carlos Gómez are among his other headliners.

Toledo, 70, is still scouting today with the Washington Nationals. He may not be done finding gems.

When I asked him what he believes his gift as a scout is, he took me back to his childhood.

Toledo recalled being a young boy and taking the allowance he earned to the neighborhood market in Santo Domingo. He always bought one particular item: baseball cards.

"I still remember the name of the lady who was the owner. Eva," he said.

He can remember the players in his first pack, too, including John Orsino, hardly a household name.

Toledo became a regular customer. Over the years, his card collection grew to total 1,500, he estimated. He studied the photos on the cards, just as he studied players on the ball fields in Santo Domingo. He created a mental library.

"I never had teaching or training in scouting," Toledo said. "That is the only thing I can say, that I started it in my mind: (studying) faces and bodies and actions, everything you have to look at in a baseball player. I think that helped me a lot more than anything else."

His dream was to play, but when those hopes faded, he began scouting in a role known as a "bird dog," an associate scout, at age 17 with the Expos.

"The agreement was you had to work with the same organization without regular payment, without expenses," he said. If his work led to a signing, he'd get $100.

He became a full-time scout in 1975 and moved on to work with the Mets from 1981-2006, the Rays through 2012, the Mariners through 2019, and now the Nationals.

For Toledo, scouting is about the power of the eye. He believes he built up an understanding of what future major leaguers look like at various stages of their development.

"If you see a photo of Juan Marichal with (Octavio) Dotel at the same age, they look nearly the same," said Toledo of Dotel, one of his Mets signings who went on to compile a 15-year career as a reliever.

That mental library of comps is what allowed him to place the skill of a then teenage Rodríguez into context. He thought he was seeing Dave Parker. Rodríguez was the best hitter he'd ever seen at such a young age and Toledo recommended the Mariners allot all their available international signing dollars to land him.

He also believes in initial impressions, in making offers quickly. Linger too long and you'll begin to see too many negatives.

He believes modern scouts have become too dependent on technology; it distracts them from what their eyes can see.

If he was watching his computer, he reasons, he never would have found Nelson Cruz.

"He was not on the list of the players I came to see that day," Toledo said. "I scout the players' actions, his athletic decisions. His love for the game. If he wants it. Does he enjoy playing the game?"

For Toledo, the human element will always be crucial in scouting.

"You leave the house early in the morning to spend all day watching players out there," Toledo said. "And when you get to the ballpark, or the field, and you open the back door of your car and get out the radar gun, computer, the Blast Motion, and this and that - you spend about 80% of the time watching the laptop and the electronic stuff.

"You forgot to watch the player."

The most hidden gem

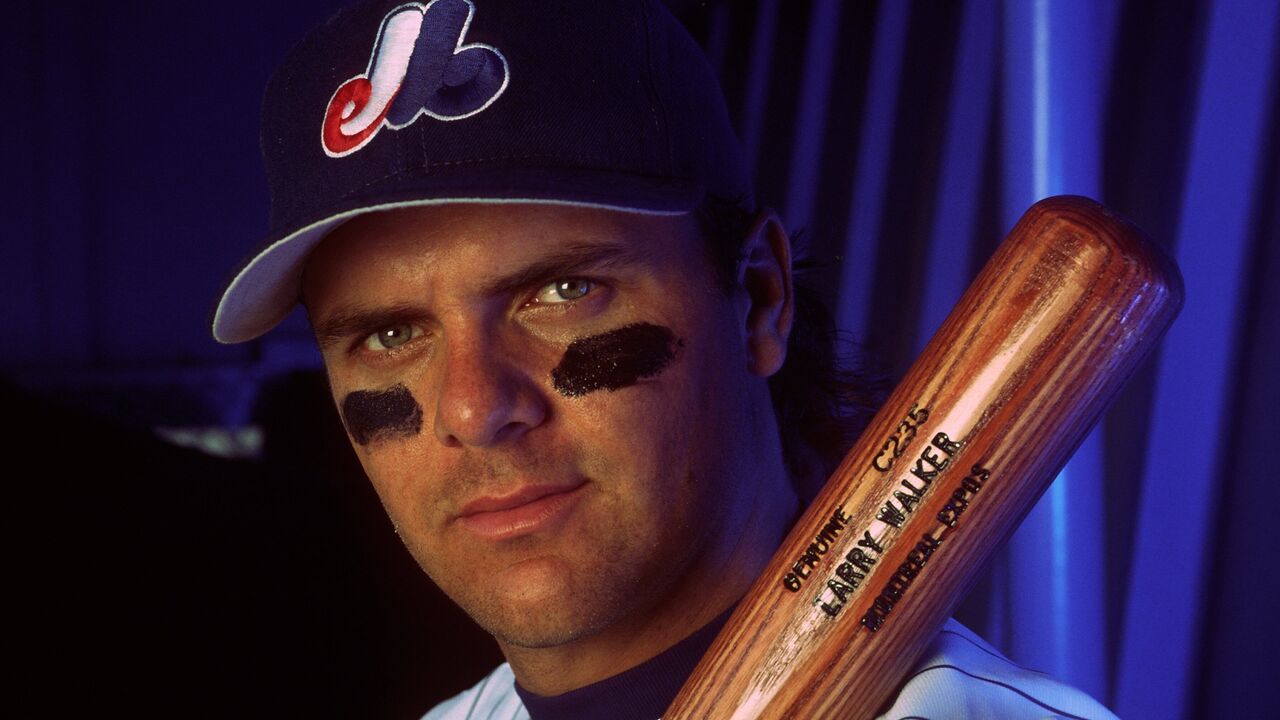

In the fall of 1984, the Expos signed Larry Walker for $1,500, one of the best returns on a signing bonus.

The first scout to see him? MacKenzie. That summer, he was coaching with Team Canada while consulting for Montreal.

MacKenzie was hosting a tryout camp in Kindersley, Saskatchewan, where the world junior baseball championship tournament was being held. Albert Belle and Jack McDowell were among the future major leaguers in the tourney. Walker was there with Team Canada, but the Maple Ridge, British Columbia, native wasn't on anyone's radar.

Walker was playing shortstop, like Raines, but MacKenzie didn't see his future there.

MacKenzie also looked past the few whiffs Walker had in batting practice, and understood he was raw - there was no high school baseball in Walker's hometown. Walker played only 15-20 games a summer until he was 16. He mostly played hockey - he hoped to be an NHL goalie as a kid - and some fast-pitch softball with his dad and brothers.

"I kept watching Walker," MacKenzie said. "He had great hand-eye coordination, quick hands, and strong hands. He had a great arm. And he could really run for a big guy."

MacKenzie was concerned Jim Ridley, who was managing the camp team, was also seeing what he was seeing. Ridley worked as a scout for the Toronto Blue Jays.

After one day of watching Walker, MacKenzie went back to his motel room and called Expos scouting director Jim Fanning.

The next day, Fanning flew to Calgary, the nearest major airport, and MacKenzie drove eight hours, round trip, to pick him up. They tried to conceal their interest in observing Walker for the entire week.

"You just see improvement in him even over a 10-day period," MacKenzie said.

Fanning called the club's western Canadian scout and told him to not let Walker out of his sight.

Canadian amateurs were not eligible to be drafted. They were signed as amateur free agents.

"It was one of the great loopholes, and no one was taking advantage of it," MacKenzie said.

By the fall they'd seen enough, and on Nov. 18, 1984, they signed Walker for $1,500. At his Hall of Fame induction speech, Walker said he "felt like I had just won the lottery," noting it was about $2,000 in Canadian dollars.

For MacKenzie, it was the second of two remarkable finds. Walker and Raines combined for 141.6 career bWAR (Walker 72.2, Raines 69.4), the best pair of signings among all living scouts.

The analytics age has streamlined the process of finding baseball players, but when it comes to the Powerball-like odds of finding baseball's gems, the best scouts still have a role in picking the winners.

Travis Sawchik is theScore's senior baseball writer.